Hoping to understand Picasso’s art but unsure where to begin? Never fear! We are Picasso experts, so we’re here to help! In this article, I’ll tell you about several of Picassos most famous artworks, why they’re important, and where to see them!

12 of the Most Famous Artworks by Picasso You Should See

When I teach students about Picasso or lead tours that include his art, they are sometimes confused about the artist. Why? Because they know Pablo Picasso is a big deal, they just don’t know why. As you look at and learn more about these famous artworks by Picasso, I think you’ll begin to see the bigger picture.

Believe it or not, Picasso could draw really, really well. According to Picasso biographer Roland Penrose, Picasso showed a true gift for art even as a boy. He got his earliest training from his father who was an academy-trained artist—quite traditional. In Barcelona, the artist got his first real training. Later, his parents sent him to Madrid for serious artistic instruction.

There are lots of stories about Picasso’s rebelliousness as a student, an artist-in-training, and a young man. While plenty of them are true, the point is that he was simply thinking outside of the box, as they say. “The box” being traditional art that features objects that look more or less real. Suffice to say that was never Picasso’s mission.

Picasso the Prodigy

What was his mission then? Miguel Utrillo, an artist who knew Picasso when he first arrived in Paris in 1900, said it best. He wrote, “The art of Picasso is very young; the child of his observing spirit which does not pardon the weakness of the youth of our time and reveals even the beauty of the horrible…”

Utrillo knew Picasso was different and that being a good artist meant more than drawing well. He also referred to the young artist as “one who draws because he sees and not because he can draw a nose from memory.” I think that says everything about Picasso and why he’s considered one of the revolutionaries of modern art.

He thought art could and should do more than mirror what we see in the real world. With this in mind, let’s look now at some of Picasso’s most famous works and where to see them.

12. Portrait of the Artist’s Mother

1896 | Pastel on Paper | Museu Picasso (Barcelona)

This touching portrait of Picasso’s mother has recently been restored—and with nearly as much love as it was made. The artist’s style at the time was what we might call “academic naturalism.” He had learned how to draw in a very traditional way. This pastel portrait demonstrates how well he did, too. However, he understood the limits of this style and would soon launch an experimental style and career that would span decades.

For the moment, though, appreciate the expertise of this portrait. Picasso expert Marilyn McCully notes that the artist made many portraits of his family members. After all, they were free models. But also, they were cherished by the family and by the artist. In this moment captured by her 15-year-old son, Maria seems to be resting. The brushwork of the dress and the background reveal the influence of impressionism.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our best Barcelona tours to take and why.

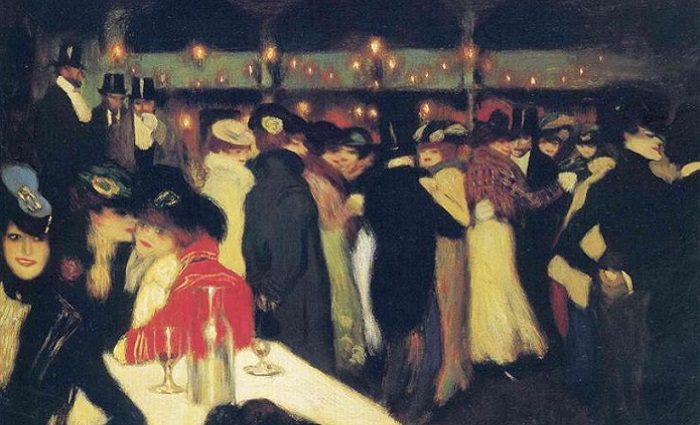

11. The Moulin de la Galette

1900 | Oil on Canvas | Guggenheim Museum (New York)

In those early days between Barcelona and Paris, Picasso’s art is reflective of the whirlwind of artistic influences that affected his style. He tried on styles like hats. It wouldn’t take him long to move on from this post-impressionist style as he chose to stay in Paris where the bohemian life suited him and the art scene was second-to-none.

Scenes of Parisian nightlife were common. Remember Renoir’s famous painting, The Ball at the Moulin de la Galette? Consider Picasso’s painting a modern update. Rather than resembling Renoir’s style, this picture captures the excitement of the bohemian nightlife, notes art historian John Richardson.

Works like this got the attention of critics and collectors. By 1901, at age 20, Picasso had his first Paris exhibition. He showcased at the gallery of Ambroise Vollard, an influential dealer who represented successful post-impressionist and newer artists. According to Richardson, a critic named Félicien Fagus called Picasso a “brilliant newcomer.”

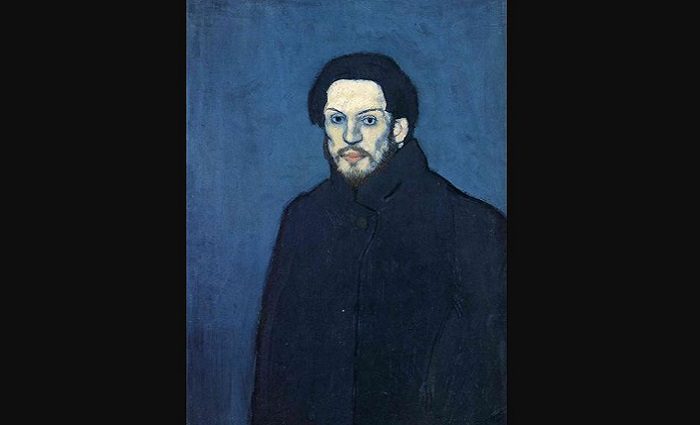

10. 1901 Self-Portrait

1901 | Oil on Canvas | Musée National Picasso (Paris)

Next up: the era of undesirables. Between 1901 and 1904, Picasso painted the down-and-out residents of Paris and Barcelona. Vagabonds, the infirm, prostitutes, and other unfortunates populate his pictures from those years.

Later, explained Richardson, art historians and critics called it his “Blue Period.” That’s because the colors he chose for these works were mostly blue and gray. For him, those colors were symbolic of melancholy.

Picasso himself was not immune to sadness and tragedy. He had lost his close friend to suicide and his art inspiration from around in 1901. Afterwards, he entered a dismal period, which is how we ended up with the self-portrait above. He looks like the gloomy, starving artist he was at the time. He was struggling to make ends meet, which explains the gaunt face.

Picasso and El Greco

The people in his art from this period tend to be slender. McCully points out that this is due to the influence of El Greco. El Greco was a major figure of the Spanish Renaissance who is featured prominently at the Prado Museum.

He painted strange, elongated human figures. Also, his backgrounds were often dark blue and filled with turmoil. I find it easy to see similarities between his and Picasso’s art, especially the Blue Period paintings, once you know what you’re looking for.

Not ready to book a tour yet? Find out how to visit the Prado Museum.

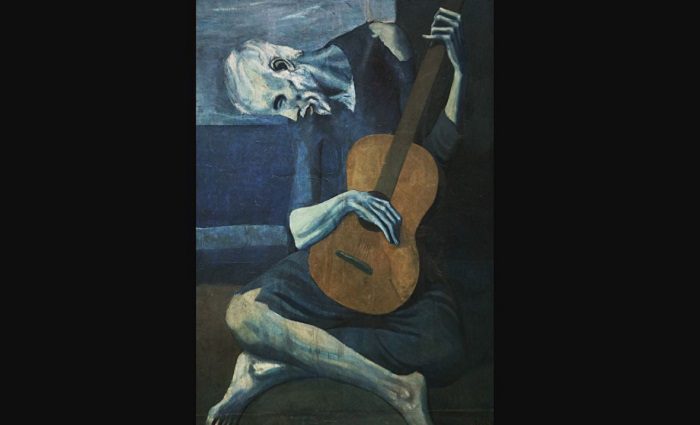

9. The Old Guitarist

Late 1903 – Early 1904 | Oil on Canvas | Art Institute of Chicago

Picasso scholars have dated his works to down to the months, which isn’t always easy to do in art. But Richardson noted that the historians wanted to track the rapid developments of his art in the early years since his style changed relatively quickly. The changes reflected his dissatisfaction and there was much more to come.

Here, the artist has represented yet another social outcast in this Blue Period painting. An elderly man from Barcelona sits on the ground in a doorway. Perhaps he is playing for people passing on the street. We don’t see a hat or tin for coins, but we may imagine he is offering his songs for a small donation.

Notice how oddly flat the background seems and how the body parts of the old man look like cut-outs. You might think they don’t matter, but these details are important on the whole. Also, the artist uses mostly blue and other muted colors. We read these colors as gloomy, which accurately describes this picture. The Blue Period paintings were the most emotionally expressive ones of his career.

8. Family of Saltimbanques

1906 | Oil on Canvas | National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.)

It’s as though the clouds have gone and the sun is shining! That’s the feeling one gets when looking at one of Picasso’s Rose Period paintings. Why? Because colors have symbolic meaning and psychological impact on us. Rose and other warm colors tell very different stories, don’t they?

Picasso’s Rose Period, which was also given that name after the fact, began in 1904. He was doing well enough to afford an art studio he called the Bateau-Lavoir. It was on the hill in Montmartre. There, he made some of his most famous early paintings.

The people in his Rose Period paintings are still marginal social figures. However, they aren’t down-and-out. They are clowns, actors, and acrobats. This group of itinerant circus performers or saltimbanques stands in a desolate landscape to which they bring good cheer.

Picasso identified with such creative types. Note how their bodies, like those of the Blue Period figures, are still strangely elongated and distorted. Remember that these are choices the artist is making to achieve a desired effect.

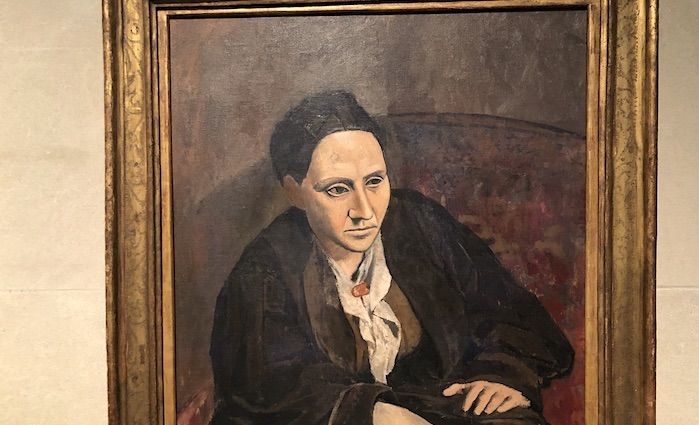

7. Portrait of Gertrude Stein

1905-6 | Oil on Canvas | Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York)

The dream of all starving artists was to find a wealthy benefactor, and that’s just what happened to Picasso. Gertrude Stein was an American writer living in Paris. She and her brother Leo were also influential art collectors. Her weekly salons—cultural gatherings—at her home were opportunities to see and be seen. Stein befriended and championed Picasso, and he finished her portrait in 1906.

This portrait one of his most notable Rose Period artworks. Why? Well, for one thing, it marks an important transition away from the despair reflected in the Blue Period paintings. For another thing, Picasso scholar Roland Penrose tells us that it’s proof that Picasso has started to work out ideas of cubism.

What are the cubism features of this painting? First, while Stein did not have a slender figure, she was by no means as bulky as she is portrayed here. So, at this stage in Picasso’s stylistic evolution, the elongated people are gone.

Second, they’ve been replaced by these sorts of figures that seem to be made up of simple, geometric shapes: cylinders, triangles, ovals, and so forth. The artist smoothed them out, of course, but you can see that objects and figures during this period look like they’ve been modeled in clay.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if a tour of the Met is worth it.

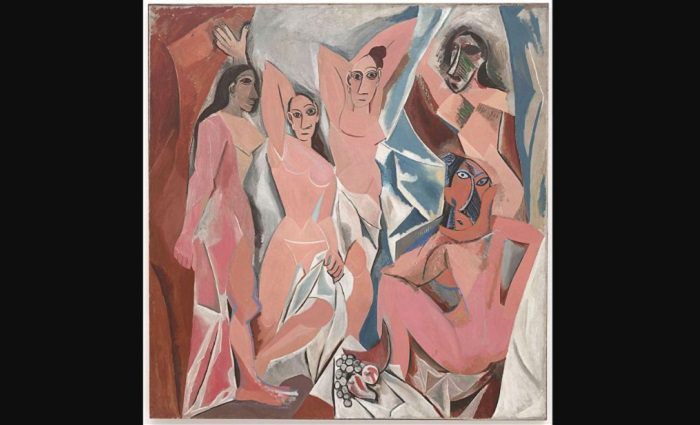

6. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

1907 | Oil on Canvas | Museum of Modern Art (New York)

This semi-scandalous painting made waves when it saw the light of day. It’s large: 8 feet by 7.6 feet. And it really only resembles the preceding Rose Period paintings based on the colors. Here, the sturdy geometric shapes of Gertrude Stein are now jagged pieces or shards of broken pottery fused together. These nude women are life-size and they stare back at you like you’re rude for looking.

Who are these so-called “Demoiselles d’Avignon”? Well, the word “demoiselles,” which usually means “young ladies,” is used in a derogatory way to refer to prostitutes. These are prostitutes from Barcelona’s red light district, which suffice to say, Picasso knew rather well. The shocking faces of these unattractive women are based on African masks and ancient Iberian (Spanish) sculptures. Why? This was the artist’s way of equating sexuality with a primitive state.

Needless to say, the public and critics who were not fans of modern art did not understand this painting at all. However, art historians now regard it as an important turning point in the development of cubism and modern art on the whole. And you’re about to see another major shift you can compare below.

5. Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier)

1910 | Oil on Canvas | Museum of Modern Art (New York)

You probably didn’t see this one coming! The change between this and the previous image of the nude women is stark, which is just Picasso’s style. Scholar William Rubin describes the fast-paced changes of cubism that happened here.

He explains that Georges Braque, another young artist working in Paris, visited Picasso at his studio in 1907 to talk about art. Braque had been painting like their hero, Cézanne. That is, he was dividing his paintings into sections resembling small cubes like Cézanne did.

Braque and Picasso became a dynamic duo creating some of the most notable cubism works of art. The first phase of cubism was later called “analytic cubism” because you had to kind of analyze what you were seeing. Artists would look at the people and objects they wanted to paint, cut them into pieces, turn them around, and putting them back together—strangely.

Why strangely? They wanted to create the sense that an object like the girl or the mandolin in this picture was being displayed from several sides all at once. Notice how the jagged pieces of Les Demoiselles above are less harsh. Also take note of the colors: brown and gray. They really don’t convey much feeling, do they? Another interesting thing is that these cubes seem to lie in very shallow space, meaning the depth isn’t as deep as you might expect.

The reason for that is that the artists wanted to challenge the idea that art should make the viewer feel like they were looking through a window at something real. Picasso and Braque thought art should do other things, newer things, and this was definitely new.

4. Still-Life with Caned Chair

1912 | Oil and Oilcloth on Canvas, Rope Frame | Musée National Picasso (Paris)

Now what, you might ask, could possibly interest an artist about an old chair? Well, scholar Penrose tells us that by the summer of 1912, Braque and Picasso had solidified their new style and were ready to experiment again. That’s when Braque came up with the idea to use non-traditional materials in their artworks, meaning, things that wouldn’t normally belong.

Keep in mind that, even though their cubist paintings, drawings, and sculptures were radical, they were still made with traditional materials. After all, what could be more traditional than oil on canvas?

So, they began adding new elements which were definitely non-traditional. The rope functions like a frame, which is meant to be funny. The oilcloth takes the place of canvas.

However, in a clever twist, Picasso simulated the texture of a caned chair. As a result, this artwork seems to have things happening on different levels. Some elements of the picture are closer to life or even real. In contrast, some are just illusions. Case in point: you’re looking at a café table with jumbled items on it, not a caned chair!

The two artists called this phase of cubism “synthetic” as they said they were synthesizing or bringing together different objects and materials. This picture also touches on themes that were common to cubism such as music and dining, especially lingering at a café and reading the newspaper or listening to live music. Just regular life stuff.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if Paris tours are worth it.

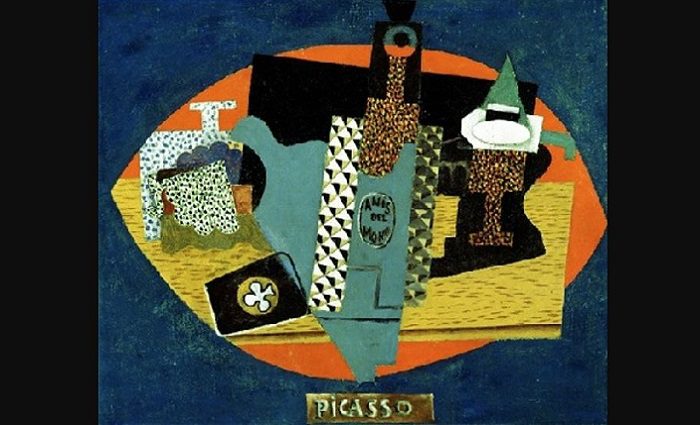

3. Bottle of Anis del Mono

1915 | Oil on Canvas | Detroit Institute of Arts (Michigan, USA)

A few years later and Picasso’s synthetic cubism has become colorful! Gone are the browns and grays. The excitement of colors is back! Although this is another still-life of ordinary objects arranged on a café table, there is a lot more happening behind the scenes, so to speak.

First, notice the bottle of liquor, the Anis del Mono. It resembles a harlequin (one of the artist’s favorite subjects) which he painted frequently during the Rose Period. Here, the bottle is decorated like the checkered costume of a harlequin. Second, remember the point I made above about different levels of representation? Well, in this case, the harlequin bottle is probably a self-portrait of the artist, according to the Art Institute of Detroit.

What other objects can you find in this enigmatic picture? A glass or two? A playing card? Perhaps a guitar or mandolin? Notice how Picasso has created the objects using solid fields of color interspersed with bright dots. Also notice how everything looks quite flat, although you still have the multiple vantage points of a Cubist artwork.

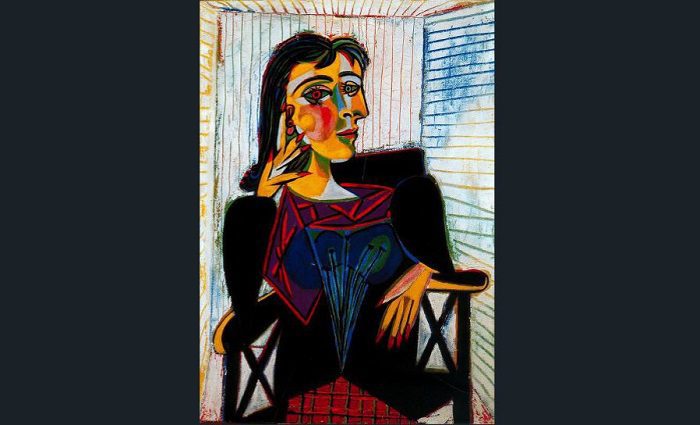

2. Portrait of Dora Maar

1937 | Oil on Canvas | Musée National Picasso (Paris)

I’m sure Picasso’s lover appreciated being painted with a double face…or did she? She and Picasso were introduced by their mutual friend Paul Eluard in 1936, though they had met earlier on a movie set, according to art historian Michel Ruten. Both were artists and both moved in a glamorous circle of artists, writers, and other cultural greats of the era.

Picasso and Maar were together for nine tumultuous years. In all honesty, all of his intimate relationships were notoriously tempestuous. He produced this strange, colorful portrait of her only a year after they’d met.

The style is surrealism, which famously featured uncanny combinations of objects and themes, hence the odd, double-face of Dora. On the one hand, it seems like she is looking directly at the artist. Then again, maybe she’s looking away. What might this say about their stormy relationship?

Writer André Malraux revealed a telling quote by Picasso concerning women: “Women are suffering machines. When I paint a woman in an armchair, the chair is old age and death, right? Too bad for her. Or it’s to protect her…” The quote is anything but flattering of the artist. In fact, he was known to be profoundly unkind to his women partners, to say the least.

1. Guernica

1937 | Oil on Canvas | Museo Reina Sofia (Madrid)

Meet Guernica, considered to be one of the greatest anti-war artworks of all time by critics and scholars alike. That’s certainly a subjective opinion but you can judge for yourself. At the least, it brings an overwhelming emotional response in the viewer, especially in person.

This enormous black-and-white (and some gray) painting measures 25.6 feet across and more than 11 feet high. Also produced in the Picasso’s Surrealist style, Guernica is considered by many modern art authorities, notes Richardson, as Picasso’s masterpiece.

But what’s it all about, anyway? Well, Guernica was a town in the Basque region of Spain. In the midst of the Spanish Civil War, a Nazi Germany condor legion of warplanes bombed Guernica. This ruthless act by the Spanish anti-Republican General Francisco Franco and his Nazi collaborators outraged the international community.

Since Spain was at war, many of the men of Guernica were away fight. Thus, the main victims of the bombing were women and children, which fueled the furor over acts of needless violence.

Picasso, a native Spaniard, painted Guernica which is filled with symbolism. The scene is a room ablaze from the bombing. A mother screams as she holds the body of her dead child. A soldier lies defeated with a broken sword. Flames rise from everywhere.

Art historian Patricia Failing points out, the bull and the horse are important symbols in Spanish art. The images in black, white, and gray tones evoke newspaper stories that told of the horror of the destruction of Guernica. When you visit this exhibit in the Reina Sofia, feel the emotions Picasso accurately portrayed here.