Wondering what other museum you should visit while in Paris? Well, the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris is dedicated to art of the early 20th century, an era of incredible artistic innovation in modern art. Here you’ll find some of France’s most famous modern artists: Renoir, Matisse, Picasso, and Monet! In this guide, I’ll share the most famous paintings to see at the Musée de l’Orangerie and why they’re so important.

Pro Tip: Planning what to do on your trip to Paris? Bookmark this post in your browser so you can easily find it when you’re in the city. Check out our guide to Paris for more planning resources, our top Paris tours for a memorable trip, and how to spend a weekend in Paris.

What You Have to See at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris

The Musée de l’Orangerie has a surprising history. Believe it or not, the building was originally a greenhouse! The royal family in the nearby Tuileries Palace used it to grow citrus trees to enjoy their daily dose of vitamin C.

However, tragedy struck in 1871 when rebels destroyed the Tuileries Palace, according to historian Hilary Ballon. In fact, they burned it to the ground but somehow the Orangerie survived. Later on in 1922, the French government transformed it into a gallery for displaying artworks by living artists. One of those artists was Claude Monet.

Eight of Monet’s nearly 250 Water Lilies paintings now occupy pride of place in the Musée de l’Orangerie—one of Paris’ top museums. This museum also displays works by some of the most radical artists of the 20th century such as Picasso, Matisse, and Cézanne. Audio guides and guided tours will take you to their masterpieces among others. I recommend using one or the other to help you navigate the galleries and learn about the artworks.

Since the museum isn’t large—which is part of its appeal—you should plan to spend about an hour at the museum. In the end, I think you’ll agree: It’s totally worth the €12.50 ticket price! Now let’s jump into my list of the most famous paintings to see here at Musée de L’Orangerie to make sure you’re well prepared for your visit.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if tours in Paris are worth it.

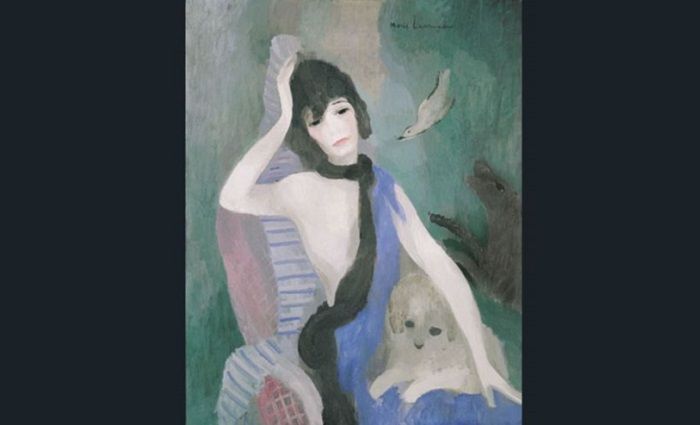

11. Portrait of Miss Chanel

Marie Laurencin | 1923 | Oil on Canvas | Level 2, Room 11

Paris-born Marie Laurencin began her artistic career as a porcelain painter for Sevres. Early on, she joined the radical Cubist rebellion, explains art historian Daniel Marchesseau. Later, she joined a group of artists, poets, and critics known as the Section d’Or (Golden Section).

In 1923, Laurencin received payment to design costumes for Sergei Diaghilev’s ballet, The Does. Diaghilev also hired Coco Chanel (yes, that famous fashion designer!) to produce costumes for his ballet, The Blue Train. The two creative women met and Chanel hired Laurencin to paint her portrait, according to art historian José Pierre.

In the portrait, Chanel lounges on a chair while a small dog rests peacefully on her lap. The soft, cool colors of the painting are pleasing to the eye. In the end, Pierre reveals that Chanel hated the portrait, so she refused to buy it. Laurencin was furious at the rejection and never painted a different one.

10. Père Junier’s Carriage

Henri Rousseau | 1908 | Oil on Canvas | Level 2, Room 13

Did you know that Henri Rousseau was a self-taught artist? In fact, he didn’t even begin his artistic career in mid-life. Instead, he spent years working as a toll and tax collector. That earned him the famous nickname, “Le Douanier” or “Customs Officer.”

Art critics considered his style naïve so they rarely gave him positive reviews. However, according to Cornelia Stabenow, Picasso and other radical artists still recognized his genius. Here’s what we know about this particular painting.

Père Junier or Father Junier, the mustachioed man holding the reins of the carriage, was an old friend of the Rousseaus. He sold vegetables at the nearby market, and his wife sometimes cooked for the artist. Evidently, Rousseau—who was often short on cash—owed Junier money.

So, the two men reached an agreement: Rousseau would paint Junier’s portrait to clear the debt. The finished portrait includes the entire Junier family. As you can see, it even includes the new horse he had just acquired.

9. The Town Hall with the Flag

Maurice Utrillo | 1924 | Oil on Canvas | Level 2, Room 14

It’s likely that Maurice Utrillo is the important postimpressionist artist you’ve never heard of. According to art historian, Gustave Coquiot, Utrillo was the son of Suzanne Valadon: artist, model, and former trapeze artist. She also modeled for artists like Renoir. Valadon was also a popular figure in the lively bohemian neighborhood of Montmartre. Utrillo grew up there and, as a result, struggled with alcoholism in his early teens.

Despite all of the above, Utrillo managed to paint really well. He is best known for his cityscapes and loved painting en plein air or “in the outdoors.” Anthea Callen notes that the impressionists, who were very influential for Utrillo, made painting out of doors almost compulsory. How else could you capture atmospheric and light effects?

This colorful piece is somewhat unusual for Utrillo because his paintings tended to feature muted colors. In fact, some appear almost monochromatic. Yet in this one, the mood is almost cheerful as people gather and converse. The blue, white, and red flag is in the center catches your eye: Vive la France!

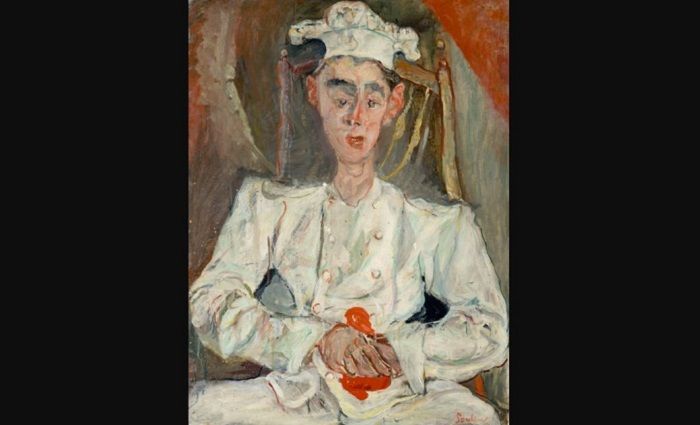

8. The Little Pastry Chef

Chaïm Soutine | 1922-23 | Oil on Canvas | Level 2, Room 15

The quintessential starving artist is epitomized by Chaïm Soutine. He lived in a run-down building in Paris called “La Ruche” (“the hive”) along with several other artists, including Amedeo Modigliani. He had moved to Paris from Belarus to make his name like many artists before him.

Soutine admired classical painting, so he tried to emulate it. He produced portraits and still-life works, but he did so with a modern twist. For example, notice how he uses bright colors and wild brush strokes. Because of this sort of distortion, portraits like this one seem like psychological studies. That said, they are not without humor as the dimpled, doughy flesh of the pastry cook seems to allude to his profession!

According to curator Karen Serres, this painting is the one that made Soutine’s career. She explains that the Parisian collector Paul Guillaume wanted to buy some paintings by Modigliani. Instead, an art critic friend told him about Soutine.

As a result, he bought this painting and it grew to fame. Later on, he wrote about it in a review, calling it a masterpiece. Last thing to note here: Marie-Paule Vial of the Musée de l’Orangerie tells us that Soutine made six different versions of the pastry cook subject!

7. Apples and Cookies

Paul Cézanne | 1880 | Oil on Canvas | Level 2, Room 10

Many art experts consider Cézanne to be the father of modern art. As curator Sylvie Patin explains, it’s because Cézanne basically invented a new way of painting. Although he began his career in the established styles of Romanticism and Realism, he felt dissatisfied with it.

So, he began his rebellion by experimenting with impressionism since he admired the way impressionist artists broke up forms by focusing on light, color, and atmospheric effects. Above all else, though, Cézanne was a rebel because he insisted that artists no longer needed to convince viewers they were looking at something real.

For example, thanks to the artistic revolution of the Renaissance, the best art could make you think you were peering through a window at life-like images. Art was supposed to imitate life. However, historians have made clear that Cézanne thought differently. He argued that photography was capable of reproducing images from real life in great detail so art should have other goals.

As a result, he began focusing on the basic tools of painting: color, form, and space. According to curator Carolyn Lanchner, the squares of color he produced were part of the inspiration for Picasso’s cubes as part of the cubism style.

Our Best Versailles and Paris Louvre Tours

Top-Rated Tour

Secrets of the Louvre Museum Tour with Mona Lisa

The Louvre is the largest art museum on Earth and the crowning jewel of Paris, which is why it’s on everyone’s bucket list. Don’t miss out on an incredible opportunity! Join a passionate guide for a tour of the most famous artwork at the Louvre. Skip-the-line admissions included.

See Prices

Likely to Sell Out

Ultimate Palace of Versailles Tour from Paris

Versailles isn’t that difficult to get to by train, but why stress over the logistics? Meet a local guide in central Paris who will purchase your train tickets and ensure you get off at the right stop. Then enjoy a guided tour of the palace and the unforgettable gardens. Skip-the-line admissions included to the palace and gardens.

See Prices

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our Paris Guide for more resources.

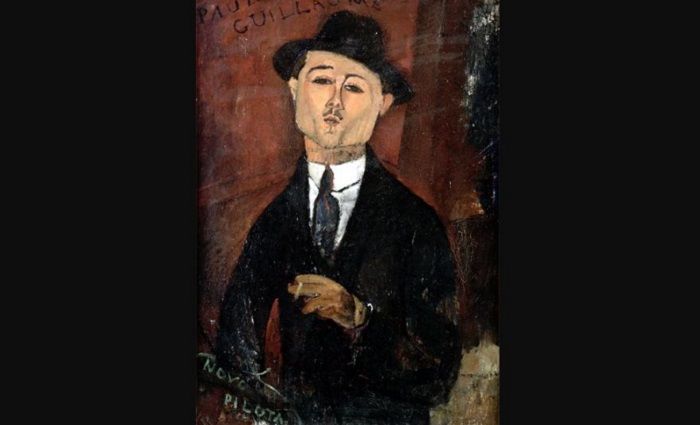

6. Paul Guillaume, New Pilot

Amedeo Modigliani | 1915 | Oil on Cardboard, Glued onto Parquet Plywood | Level 2, Room 8

Modigliani always chose to paint very traditional subject matter. For example, this portrait embodies that in terms of format and genre. However, his style was actually non-traditional, and even the materials he used were unusual at times.

In this portrait of art dealer and collector, Paul Guillaume, he used cardboard and plywood! That’s because the young artist lacked funding as many did in their early careers, explains Modigliani specialist Jean-Paul Crespelle. Quite simply, canvas was expensive and cardboard wasn’t.

Crespelle goes on to say that Guillaume was instrumental in jump starting the young artist’s career. For one thing, Guillaume rented a studio for Modigliani in the arts district of Montmartre, which was a huge break for the penniless artist. In gratitude, the artist painted four different portraits of Guillaume between 1915 and 1916.

In this one, Guillaume is just 23 but he seems more mature. He is dressed elegantly and the dark red background creates a sense of richness. Parts of the portrait are quite sketchy and there is heavy outlining, which is distinctive of Modigliani’s work.

5. Young Girls at the Piano

Auguste Renoir | 1892 | Oil on Canvas | Level 2, Room 9

It’s impossible to miss a painting by Renoir, one of the most famous French impressionist painters of them all. Forms and colors seem to turn into liquid or air thanks to the inspired brushwork of this masterful painter!

Art historian Charlotte Nalle Eyerman tells us that one of Renoir’s favorite subjects was music. Combine that with the artist’s fondness for depicting women in domestic settings, and you get irresistibly delightful paintings like this one.

In this picture, Renoir omits many details as he preferred to focus on the two girls and the musical score. According to Nalle Eyerman, Renoir frequently painted women and girls in white dresses. White seems to have symbolized femininity for him.

Apparently, he had just purchased a piano as a wedding present for his wife, so it’s possible that the scene may have been set in his own home.

4. Large Bather

Pablo Picasso | 1921 | Oil on Canvas | Level 2, Room 11

In his very long artistic career, Picasso’s style changed many times. Early on, his painting and drawing was rooted in realism. Picasso expert Kenneth Silver points out that it was almost ingrained in the artist to challenge tradition. One way he did that was by taking a favorite subject of classical art—the nude female—and depicting it with a modernist flair.

After his groundbreaking cubist phase of the early 20th century, Picasso adopted a less abstract style. In a movement that was known as “the return to order,” Picasso and others began making art that recalled ancient Greek and Roman styles and themes.

Silver notes that this more conservative style was expressed as Classical art with a modern twist, like this solid, stately bather. Images of women bathing or draped in fabric are common in the history of art, but this one is so distinctly different from the feminine versions of the past.

Note that this bather is not voluptuous—she is bulky. Additionally, her body almost resembles a sculpture and she barely fits in the space. It’s hardly what you’d expect when you envision a female bather, which is likely why we still talk about this painting today.

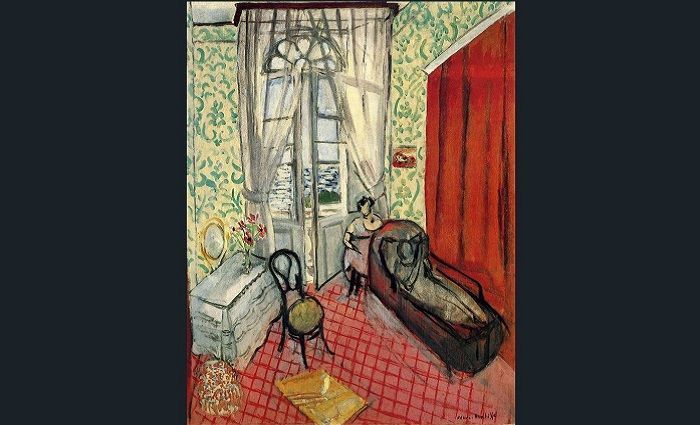

3. Women on the Couch

Henri Matisse | 1921 | Oil on Canvas | Level 2, Room 8

Henri Matisse loved color. Early in his career, writes Matisse expert Dominique Fourcade, he was a member of a small group of Parisian painters called “Les Fauves.” Fauve means “wild beast.”

They earned the name as the group preferred using bright, explosive colors over naturalistic ones. A critic gave them this name and he meant it as an insult. The artists took it as a compliment.

The colorful, light-filled room in this painting was located in a hotel in Nice. Matisse loved the region in southern France where Nice was located for its light. He often visited Nice where he painted interior and exterior scenes. Truly, he excelled at capturing the light and color.

Throughout his career, Matisse refused to paint realistic images. He deliberately distorted objects and figures for expressionist impact. In a painting, he would present multiple views of a subject or an entire scene in one picture. This technique was, in part, inspired by Cézanne and Picasso, among other of his contemporaries.

In this picture, you have a view from above. You also have a view from in front of the room. As a result, you’ll probably gaze out of the painted window. It’s an ingenious way of making what would possibly be an ordinary scene extraordinary—and colorful!

2. Water Lilies, Gallery 3

Claude Monet | 1914-26 | Oil on Canvas and Multiple Panels, Mounted on the Wall | Gallery 3

The crown jewels of this museum are without question Monet’s Water Lilies. The museum displays the paintings ingeniously. Two large oval-shaped galleries are the permanent home of eight panels of painting. Each panel is 6.5-feet high and nearly 400-feet long and are without a doubt the top art to see at Musée de l’Orangerie

This setup provides viewers like you with panoramic views of the artist’s cherished garden, including the famous water lily pond. Fun fact: The same pond is represented differently in each painting. It changes from one to the next based on the time of day, the season, or the weather.

Monet produced all of his water lily paintings after the end of World War I. France had been devastated by the war. Monet decided to create this series of paintings and donate them to the French state. For him, they symbolized peace. According to the Musée de l’Orangerie, “The eight panels evoke the passing of the hours from sunrise in the East to sunset in the West.”

The four paintings in Gallery 3 are: Clear Morning, Willows, Two Willows, Reflections of Trees, and Morning in the Willows. The word “reflection” is significant since the paintings are reflections in the water. According to curator Sylvie Patin, Monet wanted the water lily ponds to seem endless and tranquil. When you step into the gallery, you’ll probably agree.

1. Water Lilies, Gallery 2

Claude Monet | 1914-26 | Oil on Canvas and Multiple Panels, Mounted on the Wall | Gallery 2

The four panels in Gallery 2 are titled, Morning, Green Reflections, Sunset, and Clouds. These titles reveal Monet’s enduring interest in capturing atmospheric effects as impressions.

Peter H. Feist, an expert on French impressionism, explains that the movement got its name from one of Monet’s 1872 paintings: Impression, Sunrise. That painting represents a sunrise scene in the port of Le Havre in Normandy. He exhibited it at a group exhibition in Paris alongside paintings by Cézanne, Degas, and others.

Their art had been rejected by the official state exhibition called the Paris Salon. Outraged, they decided to show their work elsewhere. A critic who attended the exhibition saw Monet’s Impression, Sunrise. In a derogatory comment, he called them “impressionists.” Once again, the critique was taken as a compliment.

Monet’s Water Lilies are ethereal impressions of light effects which inspire feelings of peace and tranquility. The experience is immediate and immersive. One of the most ingenious aspects of this remarkable two-gallery display is the orientation of the huge panel titled, Sunset.

Why? Well, according to the Musée de l’Orangerie, this painting is “the most westerly composition representing sunset.” You feel as though you’re following the sun through the galleries to where it sets in the west. It’s the perfect way to end your visit to this charming museum.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if Paris tours are worth it.

Where To Stay in Paris

With a city as magnificent as Paris, it can be hard to find the perfect hotel at the perfect price. Explore the best hotels and places to stay in these incredible neighborhoods in Paris.

Leave a Comment