Where can you visit the largest museum of modern art in Europe? In Paris, of course! The Centre Pompidou is home to a huge collection of artworks by some of the most famous modern artists in one of the coolest buildings. This article shares some of the most famous artworks you’ll see at the Centre Pompidou to prepare you for a visit to Paris’ most colorful museum.

Pro Tip: Planning your trip to Paris? Bookmark this post in your browser so you can easily find it when you’re in the city. Check out our guide to Paris for more planning resources, our top Paris tours for a memorable trip, and the best museums to visit in Paris.

The Modern Art You Have to See at The Centre Pompidou

You might have passed Centre Pompidou and wondered why the building looks unfinished with people walking on the crazy outside stairs. Welcome to modern art where the building is its own version of art filled with another 120,000 other artworks. Of course, not all 120,000 of those artworks are on display at once and it’s difficult to choose just a few to highlight here.

In this article, I’ll tell you a bit about some of the most important artworks you should see at the Centre Pompidou. But first, you should appreciate the building itself, so stand outside and take in the details before heading in to see the most important modern paintings, sculptures, and more.

Patrick Sisson tells us it’s what’s known as “inside-out architecture” which means it looks like someone forgot to finish the building! Huge pipes and structural details are exposed and painted in primary colors so you can’t miss this place or the sculptures in the massive fountain nearby.

The Centre Pompidou is actually a cultural center in the very center of Paris near Le Marais. It’s also home to an enormous public library and even houses a center for music and acoustic research. However, what you’re visiting is Centre Pompidou, where you’ll see some of the best modern art anywhere in the world. As a bonus, you’ll have some of the most spectacular views of Paris (except maybe from the Eiffel Tower) as you ascend the escalator.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our best Paris tours to take and why.

13. With the Black Bow

Wassily Kandinsky | 1912 | Oil on Canvas | Level 4, Room 14

Wassily Kandinsky is one of those artists who is important, but you may not understand why when you look at their art. Picasso has the same problem. So, let me explain.

First, Kadinsky was one of the premier artists to create paintings that were almost completely abstract—nothing in his paintings is immediately recognizable. Second, he was a pioneer of the graphic arts. Over his career, his fluid shapes and forms became more precise and geometric. He taught his style and techniques at the German art school called the Bauhaus in Weimar until 1925.

Early on, though, the Moscow-born immigrant to Munich and Paris wanted his art to have a spiritual side. Kandinsky expert, Kenneth Lindsey notes that Kandinsky’s version of spirituality was somewhat intellectual and not very accessible to most people.

He was known for his involvement with the German Blue Rider Group, a collective of artists. Like Kandinsky, they thought colors, lines, and shapes could have deep symbolic and spiritual meaning. Moreover, the art could reflect the inner feelings of the artist but also be universally understandable. You be the judge when you look at his piece above at Centre Pompidou. Art can definitely have individual meaning.

12. Pig Carousel

Robert Delaunay | 1922 | Oil on Canvas | Level 5, Room 11

Can you see pigs or a carousel? It’s ok if you can’t. Sometimes it takes a minute for modern art to reveal itself, which is why we’re writing this article (and why a guide is so helpful at a museum!) At a little over 8 feet x 8 feet, this massive, colorful painting is the third version of a pig carousel, although the first version was titled Electric Carousel.

French artist Robert and his wife Sonia and several other artists established a modern style called Orphism. The science of color and optics fascinated Delaunay. His images first included recognizable objects but gradually became completely abstract with geometric shapes and other forms. One thing Delaunay loved was to demonstrate how colors interact with one another to create different visual effects and even optical illusions.

According to art historian Vicky Carl, this colorful painting is a celebration of the modern city of the so-called Roaring Twenties. The city of Paris felt like a fast-moving carousel of lights, color, and noise. Delaunay wanted to capture that sensation.

Notice the black stockinged legs of some anonymous dancer in the center. Below, near the bottom of the painting, you see a man-about-town in his jaunty bowler hat and dark car coat. Hidden elsewhere are possible pig legs, but it’s really the vibrant circles of color that express the whirlwind of life.

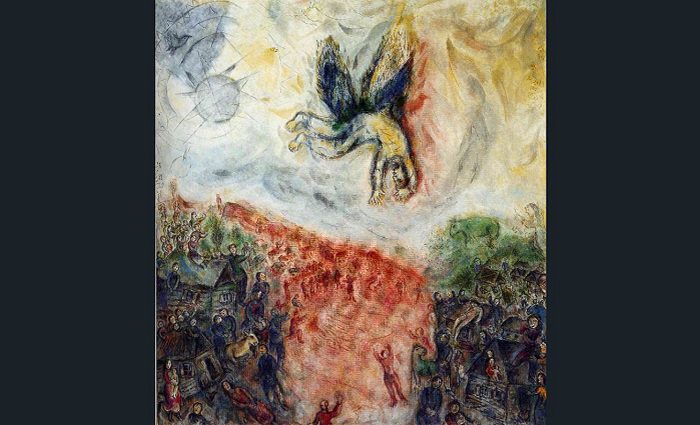

11. The Fall of Icarus

Marc Chagall | 1985 | Oil on Canvas | Level 5, Room 10

Hopefully you know about the myth of Icarus who tried to fly like a bird with feathers waxed to his arms. If not, this painting basically depicts the end result with the humor that only Chagall could add. Russian-French modernist artist Marc Chagall made this remarkable painting the last year of his life.

Chagall was everything Icarus was not. He was born of humble, Jewish origins in Russia. Like many other artists of the early 20th-century, he moved to Paris to make a name for himself. His art, explains scholar Victoria Charles, combines modernist styles and Jewish and Russian folk tales.

There is usually an element of the magical to a Chagall painting—and often humor. In this painting, the artist celebrates the human sense of adventure as much as he criticizes Icarus’ hubris. It’s as though he’s saying, “If you’re going to do something silly, do it on a grand scale.”

The sea that the mythological character is about to crash into is actually a bright void in Chagall’s home village in Belarus. He’s depicted people standing back and watching as Icarus crashes in an orange blaze of glory! A fate much worse than the actual legend!

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if Paris tours are worth it.

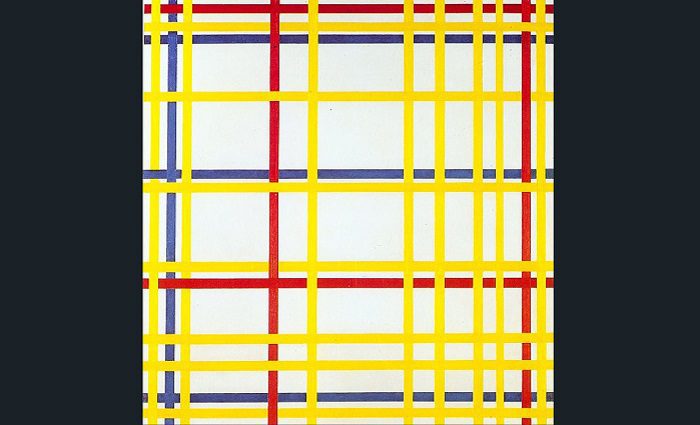

10. New York City I

Piet Mondrian | 1942 | Oil on Canvas | Level 5, Central Avenue North

It’s these kinds of artworks that often make people wonder why they don’t make similar pieces of “simple” art. Yet there’s more here to uncover which is why it’s one of our favorite artworks at Centre Pompidou. Mondrian’s signature primary colors with black, white, and gray lines and shapes are his building blocks.

The Dutch artist, like other modernists, hoped to create a new style of art that didn’t rely on representing objective reality—what you see isn’t what it has to be. For example, if you could take a picture of a landscape, why did you need to paint one? Like Kandinsky, Mondrian thought colors and forms could carry symbolic meaning. That said, his art wasn’t spiritual. Instead, it was intellectual.

This brightly-colored painting is a celebration of vibrant New York City in the early 1940s. I bet that’s not what you would have guessed this painting to mean! But you have to consider that Mondrian had fled war-torn Europe like other artists.

His art, therefore, was basically documenting his experiences of his new home—vibrancy, color, city grids, etc. In particular, notes Susanne Deicher, jazz and electric lights inspired the artist to create exuberant, abstract paintings in a style he and his collaborators had named “De Stijl” or “the style.”

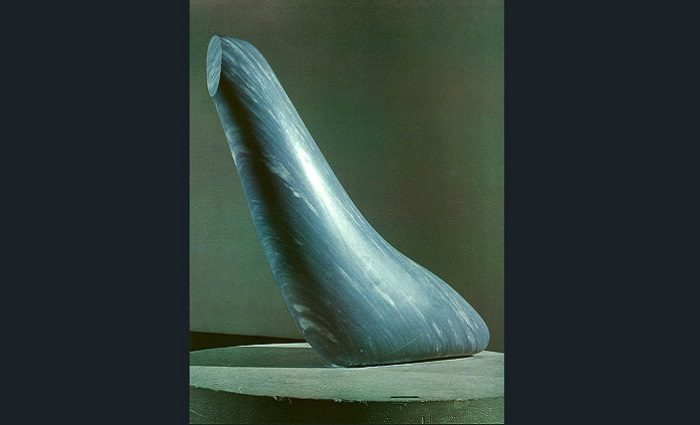

9. Seal II

Constantin Brancusi | 1943 | Blue Marble | Level 5, Central Avenue North

It’s not a bird or a plane. It’s a rock. And an unfinished one at that. This not-quite-fully-abstract sculpture is meant to represent a seal. Constantin Brancusi is thought of as the father of modern sculpture, although it would be hard to argue against Rodin who might also claim that honor.

He’s yet another artist who left his birth country, Romania, and traveled to Paris to make his way in the world of modern art. Paris and Centre Pompidou welcomed him. Not only does Pompidou display his work, but there is also a free-standing art center dedicated to Brancusi on the north end of the Place Georges Pompidou (by rue Rambuteau. It’s called Atelier Brancusi or Studio Brancusi and is well worth a visit.

The delightful sculpture of a minimalist seal comes after earlier pieces by Brancusi as he worked on more and more abstract pieces. His Bird in Space from 1923 is a brilliant visual description of a bird with just a single feather. But it also describes its flight—a graceful arc as it rises upward.

This, stresses historian Anna Chave, was the genius of Brancusi. He could tell a story with minimal words, color, and basic forms. With Seal II, it’s not too hard to see the basic shape of a seal in the blue rock.

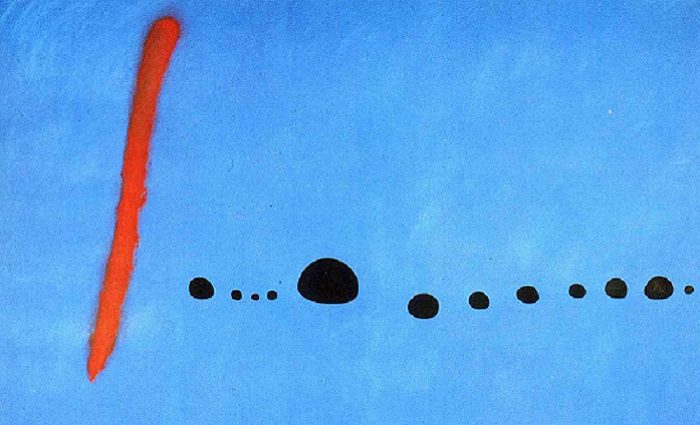

8. Blue II

Joan Miró | 1961 | Oil on Canvas | Level 5, Room 24

Believe it or not, this painting that looks pretty simple is anything but, which is why I find it fascinating. Its maker is Catalan painter Joan Miró who developed the concept of this artwork for years. It began as a series of small sketches.

At one point, explains noted art historian Roland Penrose, he tore up small pieces of paper and tossed them randomly onto a canvas of blue. His goal was to create a painting based on absolute spontaneity—no plan, no order. Ultimately, he produced a mammoth painting standing over 8.5 feet by 11.5 feet. It’s three canvases joined into one.

According to Penrose, the artist was attempting to create a contrast of two somewhat opposing ideas: quiet meditation versus wild human passions. The blue is like a sea of calm. The black dots seem to be organized and then, suddenly, there’s this wild slash of red across the huge canvas. It should be obvious that that’s the passionate part.

There’s something really wonderful about Miró making this abstract image so large. It’s like a painting of some epic event, yet everything is abstract.

7. Tree, Large Blue Sponge

Yves Klein | 1962 | Pure Pigment and Synthetic Resign on Sponge and Plaster | Level 4, Central Avenue North

The title of this artwork definitely answers the “what?” if not the “why?” Yes, this is a nearly 5-foot-tall sponge tree made from plaster and resin then painted a solid, ultramarine blue. The artist, Yves Klein, is famous for his monochromatic paintings, sculptures, and performance art.

According to Klein scholar Hannah Weitemeier, the artist co-founded an important post-WWII art movement called nouveau réalisme or new realism. Like experimental artists before them, the group wanted to create a new style of art that didn’t rely on imitating what could be seen in the natural world.

Klein named his chosen shade of blue “International Klein Blue,” notes Weitemeier. This life-size tree is one of his last artworks. It definitely resembles a tree but the title intends to make you think about the basic tools and raw materials of his art. Klein would use sponges to produce his blue paintings.

Then, one day, he had a kind of epiphany: the materials of art could also be the art! Thus, you see Tree, Large Blue Sponge. And it’s all you get.

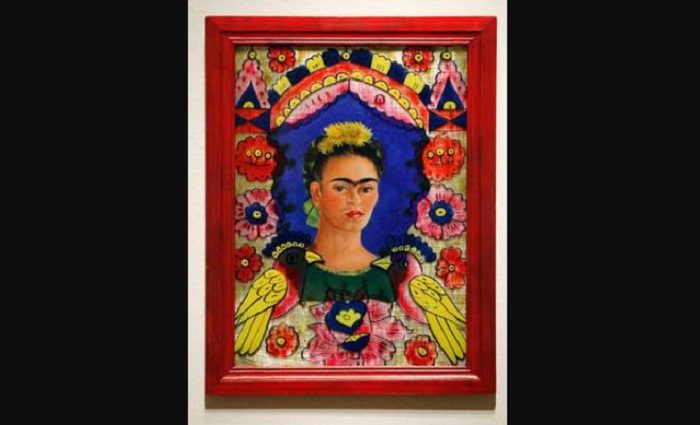

6. The Frame

Frida Kahlo | 1938 | Oil on Aluminum

At a time when male artists, like her husband Diego Rivera, were putting Mexican art on the map, Frida Kahlo was quietly making a name for herself with small, highly personal paintings. Compared to the huge murals Rivera and others made, Kahlo’s paintings explore her biography but also her Mexican heritage.

She is now one of the most famous woman artists of the modernist period, and it’s great to see the Pompidou giving her art a permanent place. Kahlo made this self portrait in the style of Mexican folk art, using a frame made by a Mexican craftsperson. This kind of frame is typically used for photographs, mirrors, or holy icons.

Kahlo painted a second frame of flowers around her portrait and gave herself a set of wings. This is significant because when she was 18, Kahlo nearly died in a bus accident. According to art historian Margaret Frith, the wings refer to the artist’s suffering or martyrdom.

Kahlo’s self portraits tend to be brutally honest. Note that she doesn’t present herself as a classical beauty. Instead, she tries to express something of her inner life that had great unrest. Despite portraying herself as a martyr, there is a celebratory feel to this painting. That was very much her style: to balance joy with suffering.

Please note: At the time this article was written, The Frame was out on loan for a temporary exhibition but due to return in early 2023. Check with the Centre Pompidou website or info desk for its location.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if Paris tours are worth it.

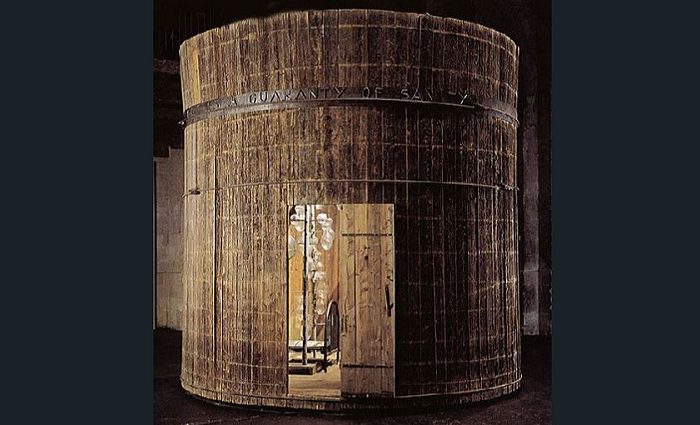

5. Precious Liquids

Louise Bourgeois | 1992 | Multimedia Installation | Level 4, Room 21

If you stood in front of this wooden water tower, you’d be completely lost as to why it’s in an art museum like Pompidou Center. Literally, why? Well, let’s dig in since there’s always a story behind each piece.

Louise Bourgeois’ mysterious installation, Precious Liquids, is a separate, intimate space located inside the open exhibition space of the Centre Pompidou. The exterior is a New York City wooden water tower. It’s what’s inside that tells a private story from glass vessels to clothing.

According to the artist in an interview with Pat Steir, the girl’s white dress is a stand-in for a young girl, possibly Bourgeois herself. The large men’s coat, in contrast, represents an influential male figure, seemingly one who has caused the child great distress. An unsettling drama may have played out, but the installation doesn’t necessarily feel ominous.

The complicated artwork has another titled: “Art is a guaranty of sanity.” You can just see it above inscribed on a plaque over the entrance. In the interview, Bourgeois is careful to point out that art is not the only “guarantee of sanity.” She explains that the main title actually refers to bodily fluids. The different fluids, such as tears, function like barometers of physical and mental health.

You might be thinking this all sounds rather complicated. So it is and it isn’t, all in one. It’s also a fascinating glimpse into the psyche of a very talented and important modern artist.

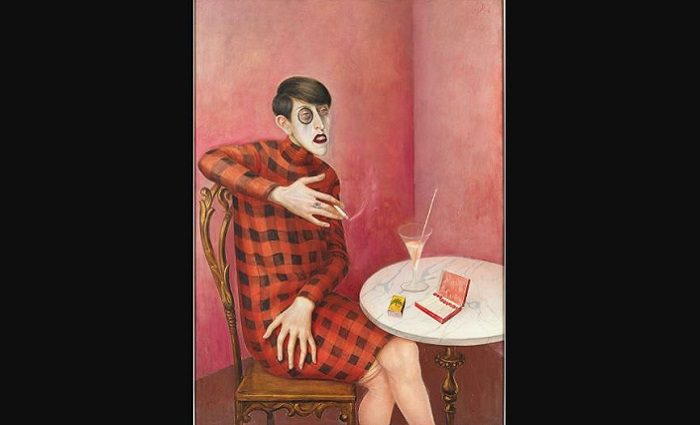

4. Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia Von Harden

Otto Dix | 1926 | Oil and Tempera on Wood

I’m sure it would be flattering to be approached on the street with an offer to paint your beauty. Well, that’s exactly what happened to journalist Sylvia Von Harden when German Expressionist painter Otto Dix met her, according to curator Marie Gispert. He exclaimed that he absolutely had to paint her portrait and she agreed.

Looking at this colorful portrait and equally colorful subject, you really have to agree with Dix. There’s something fascinating about this scene from Weimar-Era Germany Berlin. She seems to have an insider’s perspective on this exciting cultural period between the two great wars. Perhaps jaded, she smokes a cigarette absent-mindedly and waits to be amused by another friend in the artistic and literary subculture of Berlin.

Dix created a somewhat nontraditional portrait. How so? For one thing, it’s cropped like a photograph so you don’t even see her ankles and feet. For another, the objects on the centered table seem to constitute a symbolic portrait of this worldly figure. The black circle around her eye, a monocle, emphasizes the fact that she’s looking straight at us. It feels like a challenge—and an uncomfortable one at that!

Please note: At the time this article was written, this painting was out on loan for a temporary exhibition but due to return in early 2023. Check with the Centre Pompidou website or info desk for its location.

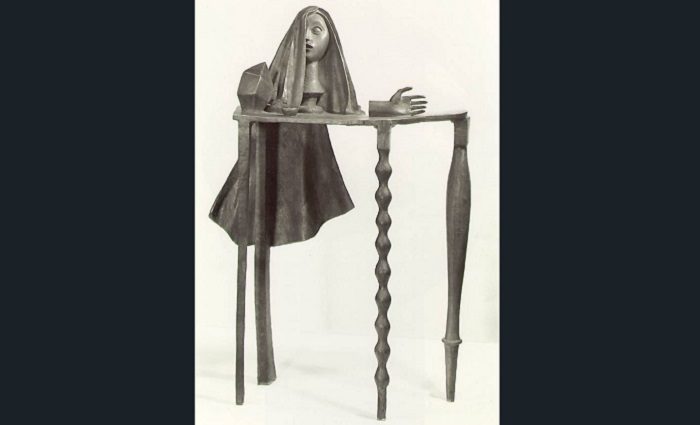

3. Table

Alberto Giacometti | 1933 | Bronze | Level 5, Room 23

There’s something unsettling and almost creepy about this sculpture. Before you get nervous, let’s jump in and discuss it. First, you should know that Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti is right up there with Brancusi as far as modern sculpture is concerned.

Giacometti didn’t go fully abstract but his work definitely pushes the envelope. You may have seen his rough bronze sculptures of striding figures that seem more like trees in winter than humans. That surrealism goes even further here. This bronze sculpture named Table feels like something from a perplexing dream, doesn’t it?

Here stands a woman at a table with mismatched legs. Wait…where are her legs? Is she the table? Is she a ghost? Giacometti’s veil on her head certainly makes it feel so. The symbolism of a veil in surrealist art is pretty clear: something is hidden beneath it. On the table, there’s a mortar used by alchemists and a detached hand. Both are tools but how do they relate to the woman?

This is what’s so fascinating about surrealism. It intentionally prompts viewers to ask questions for which there are no obvious answers. According to art historian David Lomas, the surrealists were intrigued by the ideas of Sigmund Freud, the Viennese psychoanalyst who wrote extensively about dreams.

He often talked about the way that objects, people, and ideas with no obvious connection to each other appeared in dreams. These artists thought their works could inspire viewers to look inward or find individual meaning. I think they succeeded, but you will have to judge for yourself when you see Giacometti’s Table and other surrealist artworks at the Centre Pompidou.

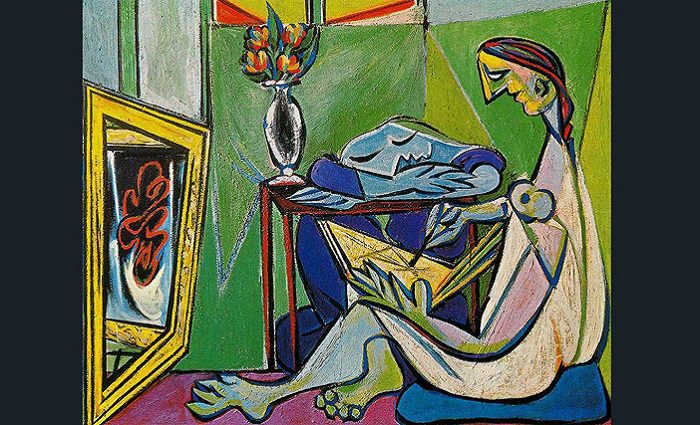

2. The Muse

Pablo Picasso | 1935 | Oil on Canvas | Level 5, Room 9

A nude portrait, a sleeping companion…but what does it all mean? You decide. Why? Because Pablo Picasso revolutionized art with his co-invention of cubism with Georges Braque, but he wasn’t immune to the appeal of surrealism. Also, he spoke highly for artistic experimentation, and he believed it was vital to adapt and change your style over time, notes Picasso expert John Richardson. And that he did!

This large painting, which measures over 4′ x 5′, is starkly different from one of Picasso’s almost monochromatic cubist paintings. It’s wildly colorful. The only things that are traditional about this artwork are the materials and the theme: traditional oil on canvas and nude women. The female nude has been a favorite theme of artists for thousands of years.

Here, the seated nude woman on the right could be making a drawing of herself using the mirror opposite her. Meanwhile, her strange blue-and-purple companion seems to be napping with her head on the table.

The entire scene seems like a weird dream, doesn’t it? Try as you may, there’s no figuring this one out. Instead, as the surrealists hope, you let the artwork speak something to you individually and find something that connects to you.

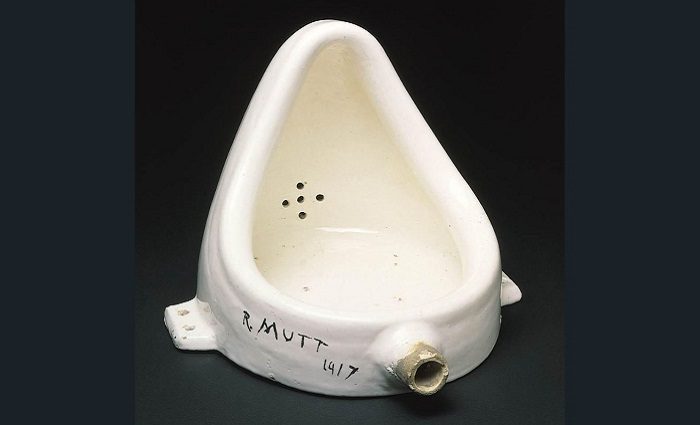

1. Fountain

Marcel Duchamp | 1917/1964 | Porcelain Urinal and Pigment

You may be thinking, “Is this a urinal? Is this a joke?” And you would be right. Yes, it’s a urinal. And, yes, it’s a joke. However, the joke isn’t on you. For the French Dada artist Marcel Duchamp, the joke was on the New York arts establishment.

Even the most avant-garde or ahead-of-the-crowd art wasn’t edgy enough for Duchamp and his fellow artists, writers, and thinkers in 1917. They were challenging everything that art stood for, including the insistence that only traditional materials could make art.

That’s why I’ve made this piece #1 on the list—it was truly a game changer. Like it or not, people did begin to rethink their conceptions of art when Duchamp pulled this historic stunt.

Duchamp took a porcelain urinal, rotated it, signed it “R. Mutt,” and submitted it anonymously to a competition of the Society of Independent Artists. Needless to say, it cause quite a scandal. From then on, he began making artworks from everyday objects and called them “Readymades.”

Curator Dalia Judovitz explains that, probably above all else, Duchamp was challenging the concept of originality. What makes an artwork original? What do you think, especially after seeing this one?

Please note: At the time this article was written, Fountain was out on loan for a temporary exhibition but due to return in early 2023. Check with the Centre Pompidou website or info desk for its location.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our best Paris tours to take and why.

Where To Stay in Paris

With a city as magnificent as Paris, it can be hard to find the perfect hotel at the perfect price. Explore the best hotels and places to stay in these incredible neighborhoods in Paris.