Always wanted to see the great Picasso’s work in Paris where he created most of his art? The Musée National Picasso-Paris is the perfect place to do that! It has the largest public collection of Picasso’s work anywhere in the world, so there’s a lot to see. In this article, we’ll guide you to the most famous must-see artworks at the Picasso Museum, so you don’t miss anything important.

Pro Tip:

- Planning your trip to Paris? Bookmark this post in your browser so you can easily find it when you’re in the city.

- Check out our Paris Guide for more planning resources.

- Learn more about our Picasso Museum Private Tour in Paris for a memorable trip

- Check out our tips on how to visit the Musée Picasso.

What You Have to See at the Picasso Museum in Paris

Did you know that just one museum holds over 5,000 works created by Pablo Picasso? Yep! You can find them at the Musée Picasso in the heart of Paris’ chic district: Le Marais. It’s filled with trendy restaurants, boutiques, and bars you’ll love exploring after your museum visit.

Picasso’s family donated an extensive personal archive of letters, sketchbooks, photographs, and more. And despite the number of works including paintings, ceramics, sculptures, and prints, it’s not a huge museum to explore.

It’s the perfect place to appreciate and discover the art and inner workings of Pablo Picasso. And a little context can’t hurt because, as art and visual culture historian John Berger wrote in his famous critique of Picasso’s art, both the artist and his artwork were complicated.

Picasso’s art was also radical and highly influential. At the Musée Picasso, you’ll begin to understand what all of the fuss was about. The museum changes its display of Picasso masterpieces every year, so some works may be rotated out to allow to allow other pieces to see the light of day. Now, step into the life and art of one of the longest-working artists of the Modernist period!

Not ready to book a tour? Find out how to visit the Musée Picasso.

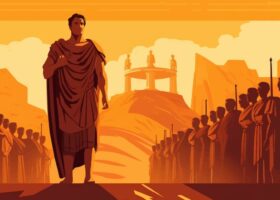

9. 1901 Self-Portrait

Pablo Picasso | 1901 | Oil on Canvas | Musée National Picasso-Paris

Picasso loved painting pictures of people considered to be social outcasts: tramps, prostitutes, and the like. In fact, he saw himself as a fringe figure, too. Still, like most artists did, he made his way from his home in Barcelona to Paris when he was 20 years old. Getting his start wasn’t easy, despite his obvious talent.

According to Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, the young artist was nearly penniless. He spent his days and nights roaming around Paris. However, he was most attracted to the bohemian district of Montmartre.

There he painted his melancholy version of Paris, notes Richardson, using cool colors like blue and gray which gave rise to the term “Blue Period.” His Blue Period lasted from 1901 to 1904.

This self-portrait is one of the first paintings of the Blue Period. He looks like one of the bohemian types he was so drawn to! The black clothing and blue background hint at his state of mind, filled with sadness over the recent tragic suicide of his close friend Carlos Casegemas, a fellow Spaniard.

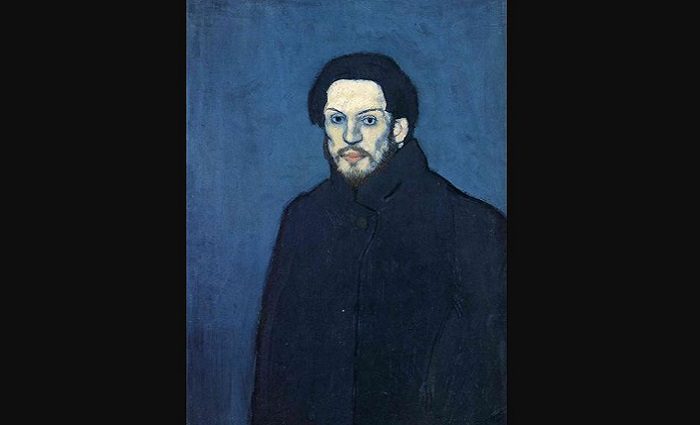

8. Paulo as Harlequin

Pablo Picasso | 1924 | Oil on Canvas | Musée National Picasso-Paris

Would you guess that this painting is of his son Paulo? There’s a lot to dissect from this portrait of a son born into the Picasso family at a time when Pablo had found his success.

Picasso intentionally painted Paulo to look like Harlequin, which is one of the characters from Italian theater where you make things up as you go—aka improv. In Italian, it’s called Commedia dell’arte. Harlequin is known to be traditionally cheerful, witty, and resourceful, and always dressed in a checkered outfit. He’s also something of a trickster, so we can suppose Picasso saw some of that in his son.

This touching portrait emphasizes Picasso’s grasp of depicting people and objects with a possibly surprising degree of realism. Yes! He could draw and paint realistically. He just chose not to most of the time while he experimented with art. As the artworks on this list demonstrate, his style changed many, many times.

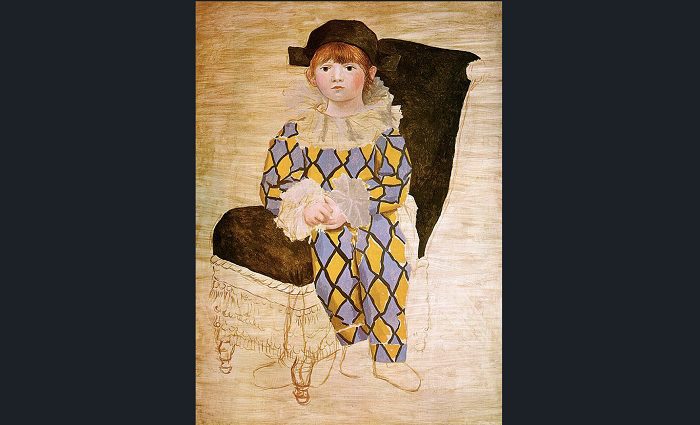

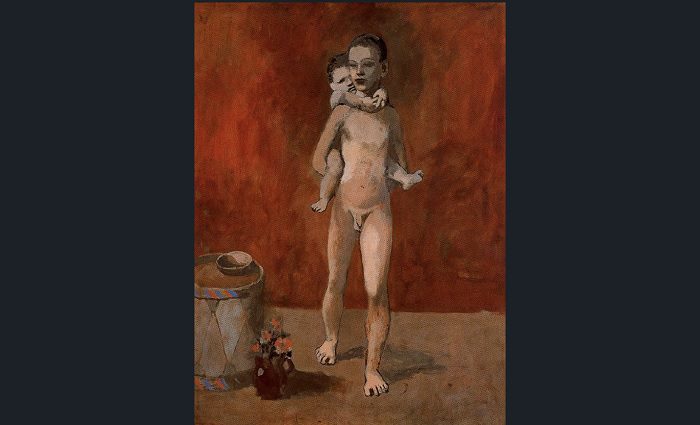

7. The Two Brothers

Pablo Picasso | 1906 | Oil on Canvas | Musée National Picasso-Paris

Now compare this work to his Blue Period of works. The warm colors like rose, red, ochre, and so forth, evoke new emotions as you look at it. So what happened? Well, Picasso traveled between Barcelona and Paris frequently until about 1904. That’s when he began doing something new in his studio in Montmartre. (He called it the “Bateau Lavoir” or “Laundry Barge.”)

Here his Rose Period began as the sadness of the Blue Period lifted. He still focused on marginal figures, however Picasso specialist Victoria Charles explains that the characters from the Rose Period are acrobats and other circus performers.

In this painting, the older of the brothers looks like an ancient Greek nude sculpture. As Charles points out, Picasso was extremely skilled at drawing and had learned how to draw and paint nude subjects in the academic style.

He pays homage to classical art even as he begins to distort figures and objects. Why did he distort them, you may wonder? For one thing, to make them more emotionally expressive. For another, he always looked for ways to make new art.

Not ready to book a tour? See if Paris tours are worth it.

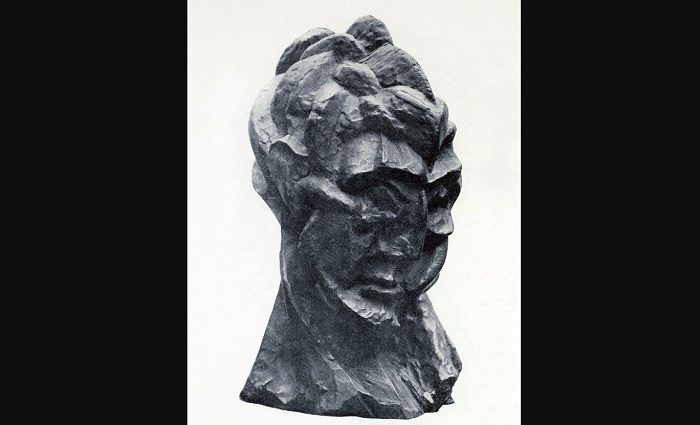

6. Head of a Woman (Fernande)

Pablo Picasso | 1909 | Bronze | Musée National Picasso-Paris

How untraditional for a woman’s features to be portrayed without the usual soft lines and feminity! This is Picasso’s first cubist sculpture. But what exactly is cubism and who was Fernande?

First, Fernande Olivier was Picasso’s lover and muse for seven tempestuous years. Fernande was an artist’s model and a true Paris bohemian. Jonathon Jones, another Picasso scholar, explains that Fernande was the model and inspiration for several of the artist’s early cubist works.

Cubism is a style of art that attempts to depict objects from more than one viewpoint. Take a good look at the bust of Fernande. It’s as though her image has been broken into multiple facets like a roughly cut diamond.

And speaking of facets, notice how geometrical all of the surfaces of this sculpture are. Now, imagine you’re floating around in space looking at this sculpture from a hundred different views at once. In a nutshell, that’s cubism.

You should know that this sculpture was not Picasso’s first cubist artwork. Art historians like Richardson and Charles will tell you it was a painting titled, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon or The Young Ladies of Avignon. That important artwork made in 1907 is at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Without going into great depth, suffice it to say that picture of prostitutes in a Barcelona brothel was a radical departure as far as art was concerned.

5. Still-Life with Caned Chair

Pablo Picasso | 1912 | Oil and Oilcloth on Canvas, Rope Frame | Musée National Picasso-Paris

What could possibly be so interesting about painting the caning on a chair? Many have asked that same question, and there are a few answers with a little backstory first.

From 1908 to 1912, Picasso began collaborating with another young artist named Georges Braque. Both of these artists, points out Richardson, were co-inventors of cubism. They called the first phase of cubism “analytic” because you basically analyze the objects since they’re divided into small facets or cubes.

In the summer of 1912, Braque had an idea: they could introduce non-traditional or unrelated materials into their artworks. Like this painting, some elements like the rope and the oilcloth don’t have anything to do with traditional painting. Basically, what are you supposed to be looking at?

The representation in Still Life with Caned Chair seems to be happening on different levels—some closer to life, some just illusions. Richardson tells us it was Braque’s idea to use the oilcloth and Picasso picked right up on it. They called this phase of cubism “synthetic” since they were synthesizing or bringing together different objects and materials.

Here’s the kicker: when you get a closer look at this small painting (11.5 inches x 14.5 inches), you realize you aren’t looking at chair caning at all! Instead, it’s a simulation. The words in the title “Still-Life” provide a major clue as to what is being represented here.

Put simply, you’re actually looking a café table! On top of the table, there’s a knife, a glass, part of a newspaper, and more. Why did you perhaps not see it at first? Because the objects are so fragmented that it’s hard to tell what they are. Welcome to the cubist revolution!

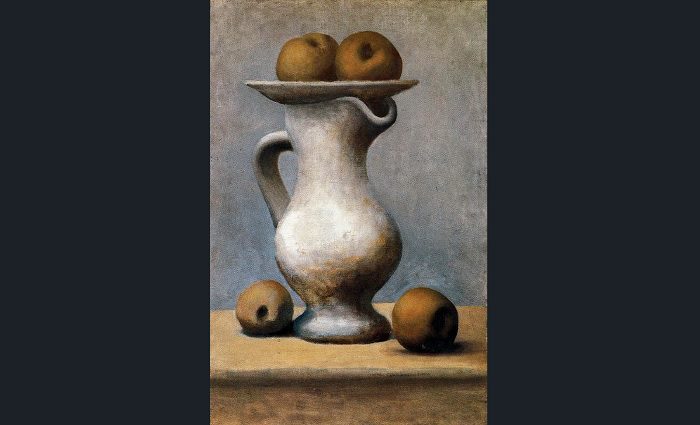

4. Still-Life with Pitcher and Apples

Pablo Picasso | 1919 | Oil on Canvas | Musée National Picasso-Paris

Just a few years later, Picasso has shifted his art again, so compare this to the two above. Picasso and Braque experimented with adding more and more color during the synthetic period. In contrast, analytic cubism featured subdued tones. Sometimes the artworks were nearly monochromatic.

When World War I began, everything changed. According to Charles, Braque went off to war where he was wounded in battle. Fortunately, he recovered and began painting again after 1917. Picasso was lucky to avoid fighting, but the war deeply influenced his art.

He transitioned completely to a different style evoking classical Greek and Roman art. Other artists did, too. It seemed safe and anything but radical in an era when peace seemed difficult to find.

The facets or cubes are gone in the pitcher and fruit above. Picasso is once again creating the illusion of depth. In contrast, cubist paintings and drawings seemed to involve shallow space. Still-life paintings like this one remained a favorite subject of the artist throughout his career according to Richardson. This rustic, pleasing picture was discovered after Picasso’s death.

Not ready to book a tour? See if Paris tours are worth it.

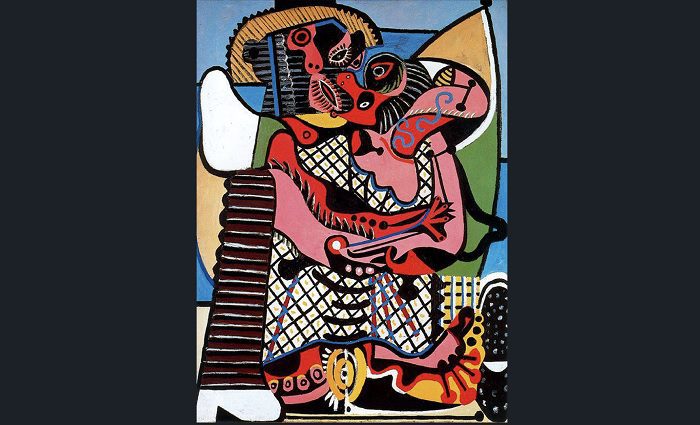

3. The Kiss

Pablo Picasso | 1925 | Oil on Canvas | Musée National Picasso-Paris

What could be more traditional than a painting or sculpture of a couple locked in an amorous embrace? Well, perhaps a painting that looks more like you and your partner in real life. Yet that is precisely why we’re still talking about Picasso, since this painting doesn’t call to mind Rodin’s famous sculpture or Klimt’s equally well-known painting.

That’s because Picasso was in his surrealist phase when he painted this colorful and—let’s face it—highly erotic picture. Well, it’s highly erotic if you can figure out what’s actually going on here.

According to art historian and curator Stephen Kern, this scene could make even the most worldly person blush. Yet it was common for the surrealist artists to incorporate erotic themes and imagery in their art.

Make sure to note that there is a commonality between Picasso’s colorful synthetic cubist paintings and his surrealist ones. If you look closely, you’ll see that in true Picasso style, he’s representing multiple viewpoints at once—and all of them are pretty racy!

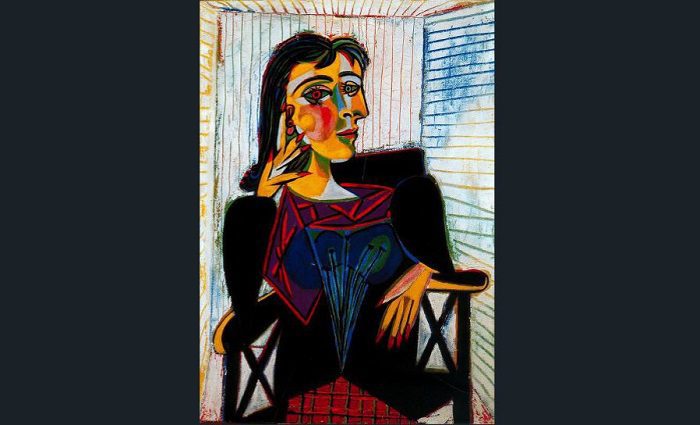

2. Portrait of Dora Maar

Pablo Picasso | 1937 | Oil on Canvas | Musée National Picasso-Paris

Would you be flattered if your lover painted you with a double expression? Well, that’s exactly what Picasso did. Meet Dora Maar. She and Picasso were introduced by their mutual friend Paul Eluard in 1936, though they had met earlier on a movie set, according to art historian Michel Ruten. Both were artists and both moved in a glamorous circle of artists, writers, and other cultural greats of the era.

Picasso and Dora were together for nine years, and he painted this colorful portrait just one year after they met. It’s created in Picasso’s surrealist style, hence the odd, double face of Dora. She is looking directly at the artist. Or is she?

The writer André Malraux revealed a telling quote by Picasso: “Women are suffering machines. When I paint a woman in an armchair, the chair is old age and death, right? Too bad for her. Or it’s to protect her…” The statement hardly casts the artist in a positive light. Indeed, he was notoriously unkind, to say the least, to his women partners.

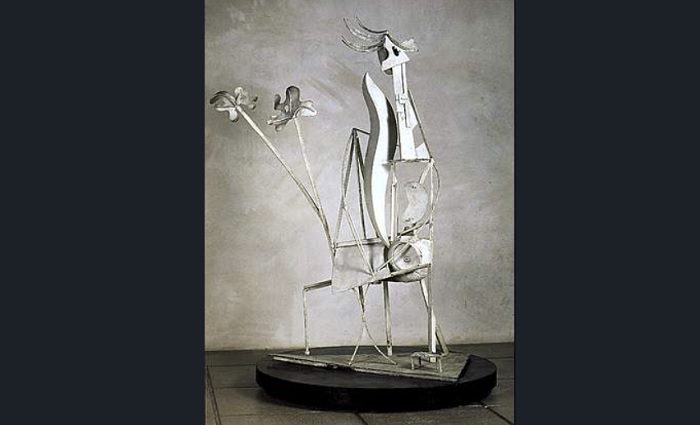

1. Woman in the Garden

Pablo Picasso | 1929 | Iron, Paint, and Solder | Musée National Picasso-Paris

At 8.5 feet by 3.8 feet by 2.7 feet, Woman in the Garden is Picasso’s largest sculpture and that feat earns our top spot on this list. Granted, it’s no David, but we’re looking at what Picasso accomplished. It’s by no means his first sculpture either.

As Carmen Fernández Aparicio explains, Picasso hadn’t used iron before making this sculpture and alternate versions of it. He asked for help from a Spanish friend, a sculptor named Julio González.

This is another surrealist artwork. It seems like a bold drawing from outer space. Once again, here is Picasso thinking about the different ways or views you can look at an object or group of objects. In this case, it’s a woman in a garden—such a simple subject like most of his artworks, yet hard to identify.

Picasso designed this artwork to pay homage to his good friend, the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire who wanted an eye-catching work of art in his garden at the Château de Boisgeloup in Normandy.

What a perfect sculpture for an outdoor garden! Like other surrealist art, there are strange aspects to it that you might not have caught, which is why it’s helpful to have someone explain what you’re seeing. The large female figure runs with her hands up and the wind in her hair. Her body morphs into leaves as she fuses with the garden. With an understanding of the art and artist, you can better appreciate its unique character.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our best Paris tours to take and why.

Where To Stay in Paris

With a city as magnificent as Paris, it can be hard to find the perfect hotel at the perfect price. Explore the best hotels and places to stay in these incredible neighborhoods in Paris.