Want to see Rembrandt’s incredible art for yourself but unsure which paintings to see or where to find them? We’ve you covered. Here are Rembrandt’s most famous artworks and where to go to see them. Hint: head to the Rijksmuseum!

Pro Tip: Planning to see Rembrandt’s artwork at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam? Bookmark this post in your browser so you can easily find it when you need it. Check out our Amsterdam Guide and our best Rijksmuseum tours to see Rembrandt’s masterpieces with an expert guide.

The 10 Most Famous Artworks by Rembrandt

Rembrandt is my favourite artist, and baroque is my favourite period in art history, so I am happy to help you understand his work! He was a very complex artist and often misunderstood. However, one thing is evident through his career: His faith.

Art historian Kenneth Clark explains that Christian culture was deeply rooted in Rembrandt, and this is something displayed in his paintings. And Greg Watts states that despite knowing so much about his art, we do not know much about his life.

Because of this, Rembrandt is often portrayed as an ignorant person. Historians considered him unaware of the great Italian masters and as some kind of misunderstood genius. But this is not true. Although Rembrandt never left the Netherlands, he knew other religions and mythology very well. Moreover, there is evidence that he saw classical pieces that were popular in his country.

But what makes him extraordinary is his understanding of the human condition. He had a natural love of people-watching. This served him well in Amsterdam and gave him a lot of inspiration for his paintings.

In addition, Rembrandt was a commercial painter. He often made his art marketable for what he thought potential customers wanted. However, according to Lois Fichner-Rathus, this played against him. When the market trends changed, his work suddenly fell out of fashion, and he grew penniless.

With this in mind, let’s look at Rembrandt’s most famous artwork and where to find them!

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if a tour of the Rijksmuseum is worth it.

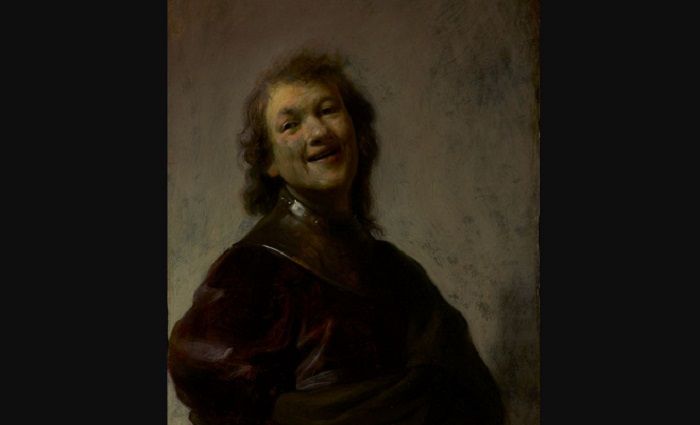

10. Rembrandt Laughing

c. 1628 | Oil on Copper | J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles)

I wanted to include this painting because it’s a painting that was actually forgotten about for many years. In 2007, it was auctioned in the UK as a generic painting from one of Rembrandt’s students. Investigations of the painting carried out later demonstrated that it was one of Rembrandt’s earlier portraits where we see the artist experimenting with expression, posture, texture, and colours.

According to Anne Woollett, the brush strokes reflect perhaps a spontaneous workflow. We think during this period, Rembrandt used himself as his model to practice and get better, so perhaps the genius had an idea and got working on the spot. More importantly, this highlights Rembrandt’s work as a self-portrait artist. We know he produced at least 40 of these pieces.

Kenneth Clark explains that Rembrandt makes these pieces seem almost autobiographical. In fact, in the last stages of his life, he painted nearly one self portrait each year, reflecting the changes in his life and body. However, Van de Wetering points out, this is likely part of his commercial approach to painting, and his knowledge that people desired these types of paintings to show off their collections.

Where to see it: J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

9. The Jewish Bride

1665-69 | Oil on Canvas | Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam)

According to Claudio Pescio, up until the 19th century this painting used to be referred to as two figures from the Old Testament. However, the painting still remains largely mysterious, and we are not exactly sure who he was trying to represent or who inspired him. However, most art historians accept the theory that these two figures are from the book of Genesis: Isaac and Rebecca.

If you want to appreciate the painting at its best, stand from a distance. This is because Rembrandt, always the innovator, used the impasto technique. According to Claudio Pescio, this technique used very thick paint bases that were worked over the surface with a knife or a brush.

Due to this, sometimes it leaves visible marks of this work, so if you look closely, you can appreciate the technique, but if you want to maximise the beauty, then look from afar. Finally, the luxurious clothing is a great testament of the rich contemporary fashion of the Netherlands at the time.

Where to see it: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Not ready to book a tour? Find out how to visit the Rijksmuseum.

8. Belshazzar’s Feast

1635-38 | Oil on Canvas | National Gallery (London)

This painting portrays the moment when the writing on the wall appears before Belshazzar. It captures an episode in the Bible that announces the fall of Belshazzar’s rule for the damage he has caused to the people of Israel.

Interestingly, Rembrandt decided to write the inscription on the wall in Hebrew. This is why the characters in the painting are puzzled. The writing is unexpected and not in a language they recognised, as they were presumably of Babylonian ascent.

According to Greg Watts, Rembrandt painted this when he was a rising star in Amsterdam in the 1630s. Furthermore, he states that the techniques used in this painting are rather different from Rembrandt’s traditional method. The colours are very rich, and the texture gives an impression of likeness to life.

Greg Watts notes that Rembrandt took a lot of inspiration from the Old Testament for this painting. He highlights that this painting is also a perfect meeting place for the natural and supernatural, as it often happens in many of the biblically themed paintings of Rembrandt.

However, Littman and Hausherr point out that the transcription in Hebrew is incorrect. It appears that Rembrandt lived in the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam for a while, so he would have asked some Jewish friend of his for help, yet his effort did not translate accurately.

Where to see it: National Gallery, London

7. Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild

1662 | Oil on Canvas | Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam)

This painting is also called “The Sampling Officials.” According to Charles Ford, Rembrandt painted this piece sometime after his bankruptcy. Despite being a successful and established artist with a workshop producing art on demand, he was not great at managing money.

Nevertheless, this painting is considered one of the best, large group portraits he made. And it is the perfect example of how Rembrandt got the viewer involved in his art. The portrait depicts businessmen from the Drapers’ Guild, and they look towards you as if you have just entered their meeting.

We know who these men were, since they commissioned the piece directly from Rembrandt, and we even have records of the guild expenditures and members. From left to right: Jacob van Loon, Volckert Jansz, Willem van Doeyenburg, Frans Hendricksz Bel, Aernout van der Mye, Jochem de Neve.

One of the things that makes this painting so amazing, according to Lois Fichner-Rathus, is that despite being a group portrait, all the individual characters look like their own person. It is not a homogenous depiction. In addition, one of the best things you can appreciate in this painting is Rembrandt’s command of light, as noted by Lois Fichner-Rathus.

Where to see it: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

6. Bathsheba at Her Bath

1654 | Oil on Canvas | The Louvre (Paris)

This is a life-size painting of Bathsheba taking a bath and one of Rembrandt’s most famous nude scenes. According to Eric Jan Sluijter, Bathsheba was a fairly common figure for female nudes in European countries north of the Alps during this period.

Moreover, in this painting, we have some classic iconographic for this depiction. Along with Bathsheba, we have the old woman at the feet and the letter that Bathsheba is holding. Anyone who was a contemporary of Rembrandt would have known the subject of this painting just from those three elements.

This painting tradition hails to the Middle Ages, where the concept of a male gazing upon a bathing woman started to become popular, according to Eric Jan Sluijter. However, in this painting, King David (who is the watcher) is missing. So, in a way, the audience act as the watchers on behalf of the king.

Another interesting aspect of this painting is that Rembrandt gives us an old woman as Bathsheba’s helper, clipping her toenails. According to Eric Jan Sluijter, this helps create an even stronger contrast between Bathsheba’s beauty and the old crone. The whole point of this is to make the allusion that Bathsheba is an alluring, adulterous woman, since Bathsheba was married to another man when she slept with King David.

Where to see it: Louvre, Paris

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if a Louvre Museums tour is worth it.

5. The Storm on the Sea of Galilee

1633 | Oil on Canvas | Unknown (Previously at Elizabeth Gardner Museum)

The reason why I wanted to include this beautiful painting is that it was actually stolen in 1990 and has been missing since then! The thieves were disguised as policemen and stole 13 artworks including this one. The heist is still unsolved despite the FBI apparently discovering the identity of the thieves in 2013.

To date, this theft is the most renowned art heist in the United States. In fact, any fans of the TV show “The Blacklist,” will remember that the fictional character Raymond Reddington is the owner of this painting. In addition, the painting is featured in the Netflix documentary “This Is A Robbery: The World Biggest Art Heist.” It was formerly in the Elizabeth Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston before being stolen.

More importantly, it is the only seascape that Rembrandt painted. The theme of the painting appears in the New Testament about the violent storm that catches Jesus and his disciples in the Sea of Galilee. We can appreciate here some of the most important techniques of the baroque era.

First, we have the chiaroscuro. Notice how the top left half of the painting is lighter than the bottom right side. And along with this chiaroscuro, the movement of the waves and the ship create a beautiful seamless diagonal throughout the whole painting that helps with the depth of perspective and dynamism of the scene.

Where to see it: Currently missing

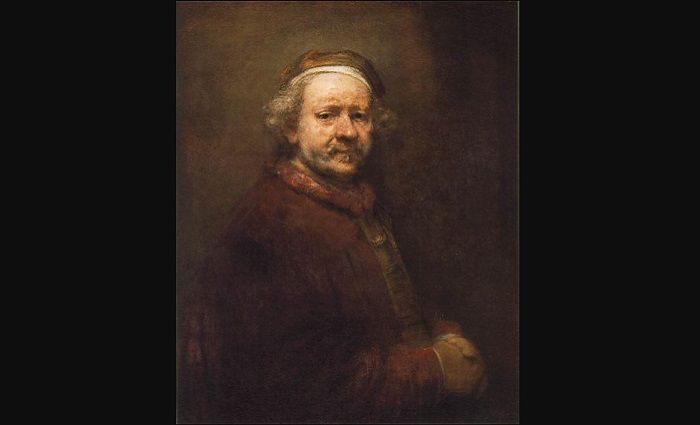

4. Self-Portrait at the Age of 63

1669 | Oil on Canvas | National Gallery (London)

Rembrandt was a prolific portrait and self-portrait artist. According to Claudio Pescio, over 40 of his self-portrait paintings have survived. This allows us to see his development as an artist. In his later years, we see a lot of rich colours and thick layers of paint used in his artwork. In fact, the last few he made look almost like something worthy of the impressionism movement.

According to John I. Durham, although the artist clearly reflects that he is now an old and weary man, the intensity of his look is still that of the sharp mind behind the artwork. Moreover, Durham says this is a very honest painting as Rembrandt doesn’t try to hide his age or labour, yet he does not give us a defeated or concerned expression. It demonstrates a great degree of self-awareness.

Finally, Durham explains how Rembrandt also manages to give the depiction of his own eyes a candid, wise look, while many self-portraits and portrait artists tend to give their subjects dead stares.

Where to see it: National Gallery, London

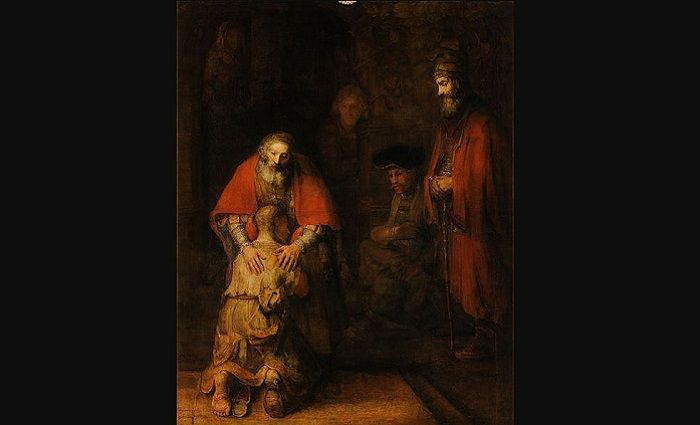

3. The Return of the Prodigal Son

1661-69 | Oil on Canvas | The Hermitage (Saint Petersburg)

According to Vladimir Loewinson-Lessing, this is the painting with which Rembrandt became a perfect artist. According to him, Rembrandt’s later works are all about the inner world of the characters in the paintings. Despite his baroque paintings and pieces often full of drama and motion, this image is almost still. Nonetheless, the message is as clear as it is in the Bible: The prodigal son has returned and all is forgiven.

The colours and the use of lighting have changed and evolved as Rembrandt becomes an older man, which we can also see in his last self-portrait on this list. He is no longer using the stark contrast of chiaroscuro. Instead, he blends light and shadow, creating an image much closer to reality. Being able to manipulate intensity, gave him more control over his painting and a bigger range and depth of feelings.

According to Sandra Forty, this painting reflects a high degree of realism and personal understanding by Rembrandt himself, as if he (as a pious man himself) was experiencing this moment.

Finally, Vladimir Loewinson-Lessing insists on the importance of this painting because of the location where it’s still found: The Hermitage in St Petersburg. Rembrandt despite going out of fashion in his home country would remain a very influential and venerated artist in Russia.

Where to see it: The Hermitage, Saint Petersburg

2. The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

1632 | Oil on Canvas | Mauritshuis (The Hague)

This is my favourite Rembrandt painting! I’ve always loved the intensity of it, as well as the fact that this painting represents—rather accurately—the way an autopsy would have been done back then. Moreover, the autopsies themselves were quite controversial. The fact that a young artist such as Rembrandt managed to land the opportunity to paint something like this is impressive.

According to Harvey Rachlin, this was Rembrandt’s first big commission. It shows the connections he had made before this moment in his career. The Amsterdam guild of surgeons used to have the first anatomy lesson of every year immortalised like this.

The year Rembrandt was offered this job, an old friend of his who was familiar with his work started working with the guild. This man was Professor Caspar Barlaeus. According to Harvey Rachlin, the guild also used to hire the services of an art dealer who worked with Rembrandt frequently. This evidence points to the fact that Rembrandt was good at networking and connecting with the right people for his commercial approach to art.

The composition of this painting demonstrates everything I love about baroque art. The diagonal line created by the corpse helps the perspective and dynamizing of the painting. And the faces are ever-so expressive, looking in and out of the picture, conveying so many emotions. This is a moment in history—a contemporary moment in history and science.

Where to see it: Mauritshuis, The Hague

1. The Night Watch

1672 | Oil on Canvas | Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam)

This is actually the known name of this painting rather than the official name which is “Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq.” It is one of his most famous works with whole books dedicated to this painting alone. The militia group in Amsterdam commissioned this group portrait in 1672.

According to Claudio Pescio, Rembrandt cleverly used colour and light to create this scene for the group instead of having them traditionally stand around a table or in an orderly manner. This technique of light contrast that he develops so well in this painting is called tenebrism.

Something that will help you identify this painting and get better familiarised with the art and historical context of the time is the addition of the muskets. They were a newer invention that can easily date painting such as these. Moreover, we know the names of at least 18 of the people depicted in this painting. According to Pescio, we even know who paid more towards this painting, because they were put at the front of the group!

An interesting thing to note is that this painting was actually a lot larger than it currently is! In 1715, it moved from its original location in the headquarter of the musketeers and put in the town hall. But the room was smaller, so they actually had to trim down the painting to the size you see now. Finally, according to Harvey Rachlin, this painting has been attacked three times throughout the 20th century by visitors, but thankfully, none have caused severe damage.

Where to see it: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if a tour of the Rijksmuseum is worth it.