From a marble-dust childhood to the heights of Rome, this timeline explains who was Michelangelo and how his genius evolved. You’ll meet Michelangelo’s most famous works in the order he made them—what they are, why they were bold for their time, and how to experience them today.

Who Was Michelango?

Before we get into Michelangelo’s accomplishments, let’s learn a little about who he was and what his life was like. Context is very important to comprehend art.

Michelangelo was born 6 March 1475 in the province of Arezzo (Tuscany). His full name was Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni. According to historian Eugene Müntz, Michelangelo saw himself primarily as a sculptor, referring to himself as a scultore. This is what he excelled at, and that is why he is considered the best sculptor of the Renaissance.

The best characteristics that describe Michelangelo’s work are sobriety and conciseness. He excelled at expressing classical beauty, movement, and the overall expression of the human body. According to Tamra B. Orr, one reason his fame lasted so long is because he lived an unusually long life for his era—88 years (d. 1564).

We also know a lot about him because he wrote hundreds of letters, which provide insight into his mind as a person and artist. Unfortunately, he had an abrasive character. Fellow artist Pietro Torrigiano often said Michelangelo came across as arrogant.

Famous Accomplishments by Michelango: A Timeline

Below, discover Michelangelo’s most famous works in the order he created them and learn where to find them now.

1475–1488 — Michelangelo’s Early Years

- Michelango was born in Caprese and nursed at Settignano, a marble-cutting village near Florence.

- His mother died when he was six.

- His father didn’t understand why he wanted to be an artist and pushed him toward something “respectable”—like banking.

These aspects of his life, work, and personality help us understand the results of Michelangelo’s artwork.

1488 — Apprentice to Domenico Ghirlandaio (Age 13)

If you had talent, it was common to be given to a master as an apprentice. Michelangelo studied with Ghirlandaio, who taught him the basic skills a painter needed during the Renaissance—most importantly, how to paint frescoes. He later wrote that he left because he didn’t think he had learned much, yet (as Tim McNeese notes) this training was crucial for his performance in the Sistine Chapel.

1489–1492 — Medici Gardens

Michelangelo studied sculpture in the Medici Gardens under Lorenzo de’ Medici’s patronage, conversed with enlightened minds (Pico della Mirandola), and had access to books few others did. He also got his nose broken, forever disfiguring him.

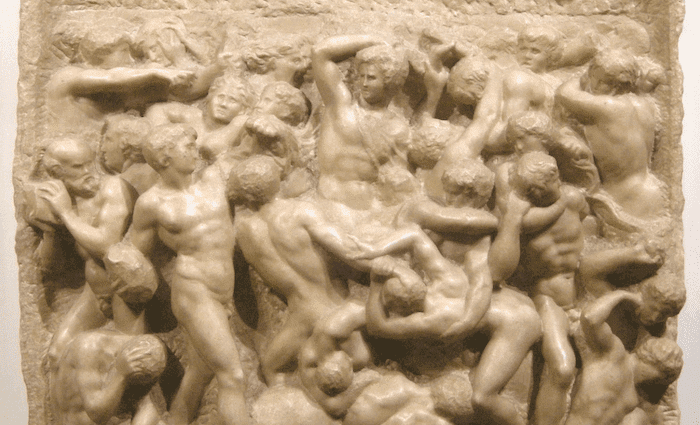

“Best Patronage”: Battle of the Centaurs (c. 1492)

Location: Casa Buonarroti (Florence)

The last work he does for Lorenzo de’ Medici, who dies shortly after. It depicts the mythic brawl at a Lapith wedding. Securing such a patron so young was a huge accomplishment. According to Gabriella di Cagno, the poet Poliziano suggested the topic—human reason (Lapiths) vs brute force (centaurs).

Michelangelo carves depth on a flat relief by tangling bodies to create volume, light, and shadow—keeping front figures more polished. He used a chisel rather than a bow drill, giving the composition a roughness that fits the brutal theme.

Side Note on Anatomy

After Lorenzo’s death, at an abbey, he became obsessed with anatomy. He performed dissections—common (if private) among serious artists—which so affected him that his stomach revolted for a time. This shocking practice fueled the lifelike power of his figures.

1496 — Michelangelo Moves to Rome

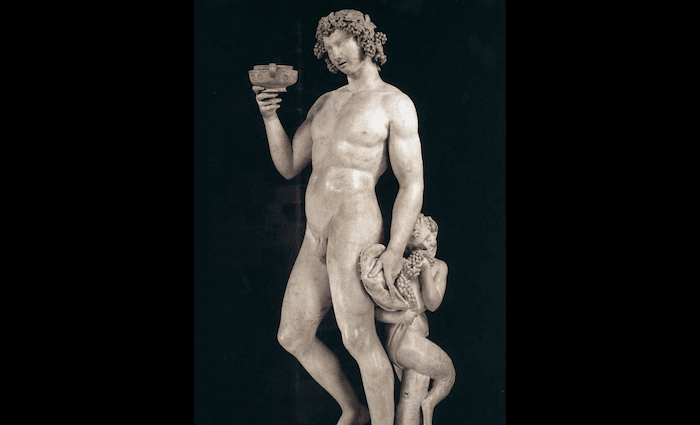

“One Man’s Junk Is Another’s Treasure”: Bacchus (1496–1497)

Location: Museo Nazionale del Bargello (Florence)

According to Lilian H. Zirpolo, it seems that the inspiration for this Bacchus came from Pliny the Elder’s description of a sculpture by Praxiteles of a drunken Baccus.

It seems that Michelangelo’s original patron for this piece, Cardinal Riario invited the artist to take inspiration from his personal collection of mythological pieces. Then, Michelangelo, who was deeply taken by Green and Roman art, took this inspiration and gave it a twist.

This depiction of Baccus as a drunken person, with his mouth agape to take yet another sip of wine, is rather uncommon. In fact, this controversial take and depiction are likely what makes the cardinal reject the piece and the reason why it ends in the possession of the banker Jacopo Galli, according to Zirpolo. That on its own is a huge accomplishment for an artist like him. He decided to stay true to his vision regardless of the consequences.

1498–1499 — First Public Commission and Signature: Pietà

Location: St. Peter’s Basilica

Originally commissioned as the funerary monument for Cardinal Jean de Bilhères, Pietà is the only piece with his signature (per Pina Ragionieri). Legend says he signed it after hearing visitors attribute it to another artist—very on-brand for his temperament.

According to Antonio Forcellino, Michelangelo captured the devotion and melancholy of Mary holding Christ. The youthful Virgin, the psychological depth, and the liquid drapery show mastery already.

See Michelangelo’s Pietà IRL

St. Peter’s Dome Climb and Sistine Chapel Combo Tour

5 Hours | €€€

See Rome from above then go deeper into the Vatican’s highlights and Michelangelo’s masterpieces.

Book Now!

Private Skip the Line Vatican, Sistine Chapel, and St Peter’s Basilica Tour

3 Hours | €€€€

Enjoy a tailored VIP Vatican Museums and St. Peter’s Basilica experience with a dedicated private guide.

Book Now!

St. Peter’s Basilica Express Tour with Papal Crypts

1 Hour | €

Marvel at Michelangelo’s Pietà, Bernini’s Masterpieces, and Sacred Tombs in St. Peter’s.

Book Now!1501–1504 — David (Florence) + International Fame

“30-Year-Old Damaged Marble Turned into Masterpiece”: David

Location: Galleria dell’Accademia (Florence)

The 5.17 m statue was carved from a weathered block abandoned for decades in the cathedral workshop courtyard (per Miles J. Unger). After four years of work, the result is a masterpiece.

- Epic move: From workshop to Palazzo Vecchio by 40 men in 4 days, then 21 additional days to raise it onto its platform.

- Why it works: Contrapposto rooted in serious anatomy study (like Leonardo), making David feel about to move.

- Model? None we can name. There are imperfections, but we pardon him since it’s so beautiful and majestic.

See Michelangelo’s David on a Guided Tour

Florence Accademia Gallery Express Guided Tour

1 Hour | €

Skip the line, marvel at renowned masterpieces and see Michelangelo’s iconic David statue.

Book Now!

Statue of David Evening Tour

1.5 Hours | €

Skip the line to see Michelangelo’s David on a later tour of the Accademia Gallery with fewer crowds.

Book Now!

Florence Walking Tour with Statue of David

2 Hours | €

Uncover the best of Florence at the Duomo and Ponte Vecchio, and skip the line at Accademia.

Book Now!“International Superstar”: Madonna of Bruges (1501–1504)

Location: Onze Lievre Vrouwekerk Church of Our Lady (Bruges)

The Madonna of Bruges is a great example of Michelangelo’s fame even in his early years. In addition, it highlights the influences that mingled in Florence during the 15th and 16th centuries. According to Müntz, there were strong trading links between Flanders and Florence.

This Madonna was, in fact, bought by Flemish merchants. The sculpture itself depicts the classic topic of the Virgin with the child. However, the child is almost standing upright without any support from the Virgin. In addition, she appears to be looking away from the child. This is probably a borrowing from his Pieta alongside the Flemish influences.

However, the most remarkable thing about this sculpture is that it became the first of his artworks to leave Italy during his lifetime. This suggests his work was good enough to receive international recognition, which many of his fellow contemporaries did not achieve.

1505 — Michelangelo Summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II

Think of it as a Renaissance “you do not say no.” Church leadership was immensely powerful.

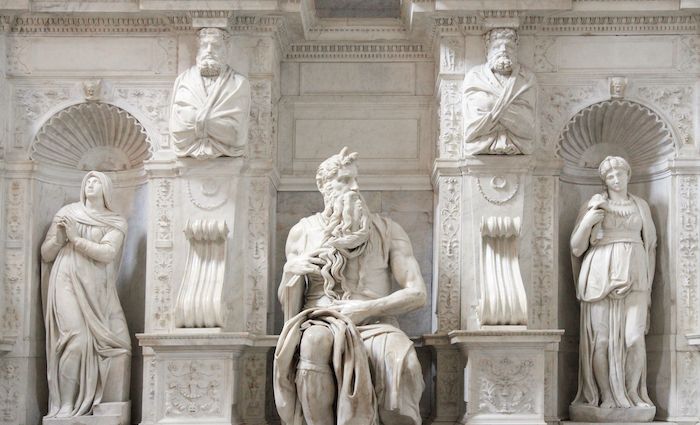

1505–1513 — Julius II’s Tomb (Moses and Dying Slave)

Location: San Pietro in Vincoli (Rome)

Moses (1513–1515, San Pietro in Vincoli) is famously horned—linked to the Vulgate description. The grand tomb was only partially completed. During the works, Michelangelo asked for more money, got refused, fled Rome, and was ordered back by an irate pope. He even made a bronze statue of Julius, which was melted down three years later.

According to Müntz, the tomb project reflects Michelangelo’s innovations: allegorical figures at the center, spiritual drama, and movement that brought effigies “back to life.”

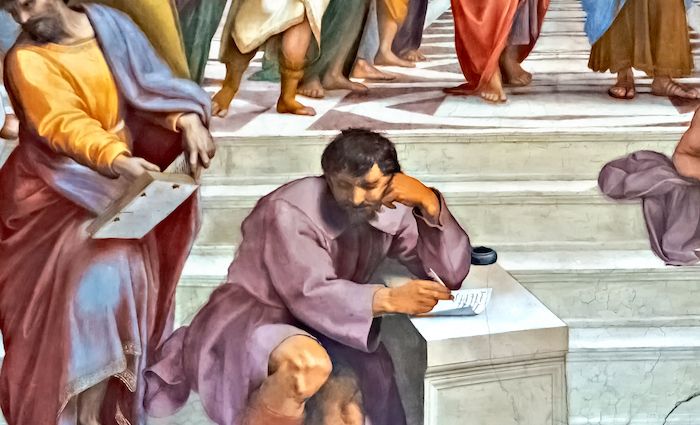

1508–1512 — Michelangelo Paints the Sistine Chapel Ceiling

Location: Sistine Chapel (Vatican)

He didn’t want to paint—and he wanted control. The plan started as apostles, but Michelangelo decided otherwise. He painted nine Genesis scenes (with The Creation of Adam the most famous), achieving dynamism and storytelling without precedent. He didn’t care about landscapes, but the nude (especially male). He slept in his clothes; apparently, his boots stayed on so long the skin came off. He wrote to his father: it is now almost 15 years since I had a single hour of well-being.

Stand Under Michelangelo’s Magnificent Ceiling

Privileged Entrance Vatican Tour with Sistine Chapel & St. Peter’s Basilica

3 Hours | €€€

Skip the line and gain direct access to the Raphael Rooms, Creation of Man & Scala Regia passageway.

Book Now!

Exclusive Sistine Chapel After Hours Small Group Tour

2 Hours | €€€€

Step inside the Vatican Museums after they close to the public for a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Book Now!

Rome in a Day Tour with Colosseum and Vatican Museums

7 Hours | €€€

Enter the Sistine Chapel, Roman Forum, and see St. Peter’s Dome, Pantheon, Trevi Fountain, and more.

Book Now!1520–1534 — Medici Chapel and Tombs (San Lorenzo, Florence)

When told some figures didn’t match Medici features, he replied: “Who will care, a thousand years from now whether those are their features or not.” It’s Michelangelo sculpting ideas—time, dawn, dusk—alongside people.

1523–1571 — Laurentian Library (Florence)

Although he didn’t finish the construction himself, Michelangelo designed the whole complex and guided successors. There’s a vestibule (ricetto), a grand staircase, and a 46-meter reading room—often cited as the epitome of Mannerism.

He used classical columns both structurally and decoratively—an artistic transgression. As Fazio & Moffett note, the staircase seems to pour into the vestibule like lava, prioritizing dramatic effect over pure function. In contrast, the reading room is quiet and serene. The patron, Pope Clement VII (a Medici), used this project to signal the family’s elevated status, from Florentine bankers to papal power.

1527–1529 — Fortifies Florence During the Siege

Appointed military engineer, he helped strengthen Florence’s defenses—proof that “artist” in this era often meant designer, engineer, problem-solver.

1534 — Michelangelo Moves Permanently to Rome

By now, Michelangelo is the most sought-after artist in Italy, balancing colossal commissions only he could manage.

1536–1541 — The Last Judgment

Location: Sistine Chapel (Vatican)

According to Sue Tatem, there are 391 human figures here. Lilian H. Zirpolo notes his unified vision—traditionally, Last Judgments were compartmentalized; Michelangelo sets Christ at the center with apostles and the Virgin, creating hierarchies by size.

Controversies? Destruction of earlier altar-wall art, nudity (per Blunt & Khan), and pagan elements in a Christian scene. Freedberg contrasts it with the traditionally less exuberant Italian approach. This all fed comparisons with Raphael, considered more decorous. Vasari describes the work’s terribilità—terror-inducing emotion.

See the Last Judgement IRL

St. Peter’s Dome Climb and Sistine Chapel Combo Tour

5 Hours | €€€

See Rome from above then go deeper into the Vatican’s highlights and Michelangelo’s masterpieces.

Book Now!

Private Skip the Line Vatican, Sistine Chapel, and St Peter’s Basilica Tour

3 Hours | €€€€

Enjoy a tailored VIP Vatican Museums and St. Peter’s Basilica experience with a dedicated private guide.

Book Now!

Vatican Museums & Sistine Chapel Tickets

Flexible | €

Skip the line and gain quicker access to the Vatican so you can explore at your leisure.

Book Now!1546 — Appointed Chief Architect of St. Peter’s (after Sangallo’s death)

1547–1564 — Michelangelo Finishes St. Peter’s Design

According to William E. Wallace, Michelangelo’s biggest achievement is the “giant order” on St. Peter’s—giving the exterior an impressive vertical thrust that unifies a previously patchwork design.

When he took over, the basilica was in rough shape: open roof, scaffolding everywhere, damaged artworks. By 1547 he was effectively the supreme architect and dedicated the rest of his career to it. Pope Paul III wanted exclusivity, pulling him from other work—but he gained freedom to execute his design.

Does it sound odd that a painter was an architect? Remember, Raphael was too. These were Renaissance polymaths who studied ancient Roman architecture. It took over a century to build St. Peter’s; in today’s terms, a project like this would cost in the billions.The dome—one of the largest in the world—even includes a stairway to the top. As you like to say: he basically thought, “maybe tourists will want to climb this in 500 years—I’ll build a staircase!”

1550s — Urban Rome: Capitoline Hill and Porta Pia

Late-career, Michelangelo reshaped Rome’s civic spaces with the Capitoline Hill plan and the Porta Pia projects that still frame the city today.

1564 — Michelangelo’s Death and Burial

He dies in Rome at age 88 and is buried at the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence. According to Tamra B. Orr, his long life helped cement his influence; his hundreds of letters let us know the mind behind the masterpieces.

Throughout His Life — “Prolific Poet”

Want in on a huge accomplishment not many people know? Michelangelo wrote 300+ poems—sonnets and madrigals. According to Chris Ryan, Michelangelo admitted he wasn’t the best with language, but he kept at it. Some poems were published in his lifetime, possibly by admirers (or critics).

Ambra Moroncini says the poems reflect a religious journey from traditional Catholicism to Neoplatonism; Glauco Cambon notes early humor and transgression, which mellow with age. Amid a frenetic career, producing such a volume of literature is absolutely an accomplishment.

Final Thoughts

You don’t need an art degree to “get” Michelangelo—just a good sequence and a few things to look for. Save this guide, plan your route, and when you’re standing under David or the Sistine ceiling, you’ll know exactly how those moments fit into a remarkable life.