With millions of annual visitors and a massive collection of important artifacts and artworks, visiting the British Museum can be overwhelming. To help you have a meaningful experience of this incredible London museum, our local expert has put together a list of must-see paintings, sculptures, and artifacts. Here are the top things to see at the British Museum.

Pro Tip: Planning what to do on your trip to London? Bookmark this post in your browser so you can easily find it when you’re in the city. Check out our guide to London for more planning resources, our top London tours for a memorable trip, and how to see London in a day.

Top 12 Things to See at the British Museum in London

The British Museum tells the story of empire and conquest through its collection of spoils of war. As one appreciates the majesty and beauty of each artifact, we are reminded that the museum was created at the zenith of Britain’s power.

Not only do we imagine Persian, Aztec, and Yoruba empires from hundreds or thousands of years ago, we think of the very recent British Empire, and how it changed the world forever.

This collection only exists because of the British Empire’s far-reaching boundaries, a supreme sense of superiority, and an appreciation of the beautiful. Read on for the top things to see at the British Museum.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if London tours are worth it.

12. The Parthenon

Ancient Greece | Artist Unknown I Room 18

Around 1800, Lord Elgin (Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin) plucked these relief carvings, called metopes, from an ancient Grecian temple. This was not any old temple, packed away in sand and dust. It was the Parthenon, the temple to the Goddess Athena, set on the acropolis in the heart of Athens.

Lord Elgin claimed to have permission to loot the temple, but even at the time, the removal of these metopes was controversial. Famed Romantic poet Lord Byron weighed in, publicly denouncing Elgin by name in his poem, “The Curse of Minerva.”

Yet here the sculptures and reliefs remain, 200 years later, and it’s a privilege to look upon them, as the ancient Greeks, their friends, and foes once did. Imagine them adorning the temple in 400 B.C., brightly painted, shouting the glory of Athena, Athens, and their empire.

Champions of “civilization”

There is a sublime beauty in the mastery of the human form. Notice how everything is perfectly proportional, a perfect balance between the figures and their movements. This is a departure from the Greek Kouros, the strong, stiff, lone sculptures copied by the Ancient Egyptians. The Parthenon characters speak to us in a modern world because they are timeless. They are as fine examples of graceful artistry now as they were to the ancient Greeks.

Yet, in addition to creating something beautiful, there is a clear message communicated in these metopes. They tell us about the people who created them and what they valued. They reveal what this civilization prized more than anything in the world: the glory of their empire.

We turn to Mary Beard, a Cambridge classicist, who explains, “one of the ways that Athenians thought about their position in the world, and their relationship to those they conquered or abominated, as they saw the ‘enemy’ or the ‘other’ in terms that were not, in a sense, ‘human’. So what you have on the Parthenon is different ways of understanding the ‘otherness’ of your enemy.”

The mythical, distinctly non-human creatures, like the centaur, represent their enemies, the Persians, and Spartans. Greece had to fend off its culture from “dehumanizing” forces and protect “civilization.” If you’re waging war, which Athens often was, this is a powerful concept to rally behind.

How does Greece feel about this?

Greece has asked, pleaded, and demanded that the treasures of the Parthenon be returned. The British Museum said, “I’m so sorry, old chap, they belong here with us.”

11. The Younger Memnon

Ramses II of Egypt | Artist Uknown | Room 4

First, let’s be clear. This is not a statue of Memnon, young or old; that’s a misnomer carried down through the ages. We’d like to introduce you to Ramses II.

One of the greatest and longest-ruling pharaohs of ancient Egypt, Ramses II ruled until his early 90’s. His empire stretched far in every direction. Acutely aware of the power of iconography, he immortalized himself and his many military victories in temples, tombs, and statuary.

Two thousand years later, the Emperor of a different empire, Napoleon Bonaparte, sought to capitalize on Europe’s hunger for all things Egyptian. He led a modest-sized expedition to conquer Egypt and haul back all of the spoils of war.

The French and British take turns looting

When Napoleon’s soldiers found this impressive bust of Ramses II, they wanted to keep it. It weighs roughly seven tons, so they bored a hole in its side to pack it with explosives. The idea was to blow poor Ramses into several smaller blocks and reassemble it at the Louvre. The French abandoned the plan and Rameses to the desert, but you can still see the hole.

Fifteen years later, British Consul General, Henry Salt, decided that England should have Ramses II. He commissioned explorer Giovanni Belzoni with the task of bringing the statue to England. Belzoni and his complex system of pulleys, hydraulics, and rolling poles were eventually successful. It took about 130 men and 15 days to transport it several miles to the Nile River.

The statue then sailed down the Nile and onwards to London. The English were beyond excited to receive the bust of Rameses II. Capturing an icon of the greatest Pharaoh in history seemed to signify that Britain was the world’s new empire.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, composed his poem, “Ozymandias,” the Greek name for Ramses II. The poem calls out the hubris of man, the false ideology of power, and the certain fall of empires. The episode of “Breaking Bad” when Walter White’s drug ring collapses is also titled “Ozymandias.”

What does Egypt say about this?

Egypt asked for Ramses to be returned. The British Museum took a sip of tea and said, “I think you mean Memnon, and he doesn’t want to leave.”

Popular London Tours

Best Selling Tour

Legends and Lore Tour of the Tower of London

The Tower of London’s maze-like layout and endless crowds can leave you lost, missing key sights and powerful stories. Our guides ensure you won’t miss a thing. Begin with a Thames boat ride to the Tower, then follow your expert guide through its historic walls to see the dazzling Crown Jewels. From chilling tales of betrayal to towers where history’s most infamous figures met their end, this tour unlocks the secrets of London’s iconic fortress.

See price

Top Selling Tour

London Walking Tour with Westminster Abbey and Changing of the Guard

Without a plan, visitors to London end up missing Westminster Abbey’s hidden stories and losing out on the best view of the Changing of the Guard. With us, skip the line and enter Britain’s most iconic church, led by an expert who reveals royal secrets from coronations to ancient tombs. Then, secure the ultimate spot to witness the Guard’s iconic march. Don’t settle for rushed glimpses—this tour is your key to experiencing London’s grandeur with nothing left unseen.

See price

Not ready to book a tour? Check out the best London tours to take and why.

10. Oxus Treasure

Persian Remnants | Room 52

We remain in the ancient world, on the outskirts of the Persian empire, over 2,000 years ago. In the 1880s, the Oxus treasure, containing magnificent gold coins, statuary, jewelry, and vessels, was discovered on the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan.

According to historian Tom Holland, the Persian “King of Kings controlled everything, but at the local level, he was represented by a governor—a satrap—who would keep a close eye on what was going on in these subordinate kingdoms. He would enforce law and order, levy taxes, and raise armies.”

If you look closely at the golden toy chariot, you’ll notice that it carries a satrap, dressed in a Median costume and wearing a headdress. The carriage itself is outfitted for speed, pulled by light and fast Arabian horses. High-spoked wheels allowed it to travel along the well-kept roads throughout the empire. You can see an emblem of the Egyptian God Bes, a talisman for good luck and protection, on the front.

The Persians: early adopters

This iconography indicates that the chariot was most likely made in Iran, a melting pot of traditions, cultures, and religions. Contrary to the Roman approach to empire building, the Persians conquered territory and then left it alone. However, they did collect taxes, establish trade, and embrace aspects of cultures they found useful or compelling.

The Greek historian, Herodotus, observed, “no race is so ready to adopt foreign ways as the Persian; for instance, they wear the Median costume as they think it handsome than their own, and their soldiers wear the Egyptian corselet.”

This one golden object, no bigger than a toy, shows us how the Persian Empire was ruled. We can see how it absorbed traditions from those it conquered. And we’re able to imagine its bureaucrats racing around the empire in fast chariots on good roads, collecting taxes.

What does Tajikistan want?

The Tajikistani President has asked for its treasure back. The British Museum instead presented the nation with a beautiful golden copy.

9. Kakiemon Elephant

Porcelain | Room 92-94

Our two elephants tell a complex story of empires and trade, beginning with the 17th-century European madness for porcelain. When the Chinese could not keep up with European demand, importers turned to Korea and Japan.

By the 15th century, the Koreans had adopted the porcelain process from China and introduced it to Japan. These three civilizations often traded art and technology back and forth, improving upon technique and customizing the style.

Japan, closed off to most of the world, had only one trading partner, the Dutch India Company. For over a century, the Dutch India Company harnessed its contacts, wealth, and innovation to become the world’s leader in trade. They alone had access to Japanese porcelain treasures; they alone could supply the eager British collectors and fill the drawing rooms of country estates and London townhomes.

So in essence, while these are charming, slightly whimsical elephants, they convey a much larger story, one of the interplay between three great empires, China, Japan, and Korea, and a fourth superpower, the Dutch India Company.

White Elephant Parties

Rulers of the Far East gave white elephants, a symbol of power and good fortune, as gifts. However, the recipients, fearful of offending the giver, could not put the beasts of burden to work. Consequently, white elephants, which were very expensive to maintain, were largely useless, overly extravagant gifts. Hence our modern term, a white elephant gift.

Do the Japanese care?

The Japanese have not asked for these elephants back—but then again, who wants a white elephant gift?

8. Mechanical Galleon

Holy Roman Empire | Room 39

Hans Schlottheim, a master clockmaker, created this ship for the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II in the late 16th century. A pretty toy, it took the craze for automation to the next level. Its clock hands move, organ pipes sound at the hour, little sailor-lookouts move around the deck, and the cannons fire while it wheels itself around. While the ship was fun to play with, it was really a chance for the Emperor to show off his latest and coolest technology.

Ships were the highest form of advanced technology of the day. They made trade, exploration, and warfare possible. However, in addition to representing the power of the empire, the ship is also a symbol for the Emperor himself. The emperor is the captain. In fact, the word “governor” comes from the Latin for helmsman, “gubernator.”

Rudolf sharing his toys

We picture Emperor Rudolf II sitting at a long banquet table, perhaps bored by another stuffy state dinner. He winds up the ship and away it sails, down the table, self-powered, firing cannons, playing music, correctly announcing the time of day. It was magical and impressive, but also probably a lot of fun.

Historian Lisa Jardine perhaps says it best, “I just think humankind is fascinated with things that move and turn under their own steam—that you can wind something up and it goes without you touching it. We just love it, always have done, always will.”

Do we have to give this one back?

The Holy Roman Empire has not asked for its toy ship back.

7. Lewis Chessmen

Scotland | Artist Unknown | Found 1831 | Dated to 1150 A.D. | Room 40

Mystery shrouds the discovery of these chessmen. Legend says a local farmer found this cache of chessmen in 1831, buried in a sand dune on the Scottish Isle of Lewis. The island was a part of the vast Norse empire, so it’s possible someone found and hid the pieces hundreds of years ago after a merchant ship wrecked.

Historians agree that the chess pieces date from around 1150 A.D. While most believe they were probably crafted in Norway, there are competing theories, including that it was Margret the Adroit who carved the pieces in her native Iceland.

The Lewis Chessmen vary in size and archaeologists believe that the 79 pieces came from 5 different games. Some were painted red at one point, and each is carved from either whalebone or walrus ivory.

Ron Weasley loves this game

Today, these chessmen captivate the imagination. Adopted from faraway India and Islamic empires, the game of chess adapted to appeal to European tastes. In this Scandinavian set, the Queen represents the Virgin Mary and the pawns are mythological Norse berserkers.

They have peculiar expressions, which appear quirky and comical to modern audiences. Scholars argue, however, that this game was not supposed to be silly. It was, in fact, a war game, used by knights to sharpen their strategic thinking. The pieces represent the strict feudal caste system in place across Northern Europe.

The pieces themselves served as inspiration for the fantastical giant-sized game of chess in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. The massive game pieces in the film are exact replicas of the Lewis Chessmen, in all of their eccentric glory.

What does Scotland say?

The Scots, at least some of them, have asked for their chess pieces back. The English literally responded, “It’s a lot of nonsense, isn’t it?”

6. Royal Game of Ur

Iraq | Dated to 2300 B.C. | Found in 1930s | Room 56

On to another game from another empire. Sir Leonard Woolley found the Royal Game of Ur during a British Museum dig in Iraq in the 1930s. The dig was a huge success and uncovered the Royal Cemetery at Ur, a collection of intact burials filled with treasure dating from 2300 B.C.

Archaeologists have found subsequent games throughout the Middle East and India and the British Museum’s own Irving Finkel discovered the rules to the game in the 1980s. No one is sure why the game fell out of favor, but it is clear from the evidence that it was incredibly popular in ancient Mesopotamia.

The fact that it was found in a vast royal tomb means that the people of Ur decided that their ruler couldn’t possibly face the afterlife without this game. Their king, and perhaps the servants sacrificed to join him, might suffer boredom. By packing the game in with all of the other necessities of the afterlife, they were sure to have entertainment.

Lawrence of Arabia and Agatha Christie

Sir Leonard Woolley was a fascinating character in Colonial Britain’s empire. Friends with Gertrude Bell and T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), he was a well-trained archeologist and sometimes-spy. He worked on digs during WWI, which allowed him to monitor the progress of the German Berlin-Baghdad rail line. However, Turkish forces sank his ship and he spent the rest of the war in a prisoner camp.

He married a fellow archeologist, Katharine Keeling, who helped him raise funds, publish his writings, and sort artifacts. The couple became good friends with Agatha Christie, who set her novel Murder in Mesopotamia at the Royal Cemetary of Ur.

You’re saying looting wasn’t just an 18th and 19th-century problem?

It doesn’t sound like Iraq is asking for the Ur treasure back, but to be fair, they have been busy tracking down all of the treasure looted from their museums and historic sites over the past 20 years. They recently negotiated the return of 17,321 stolen artifacts from the United States.

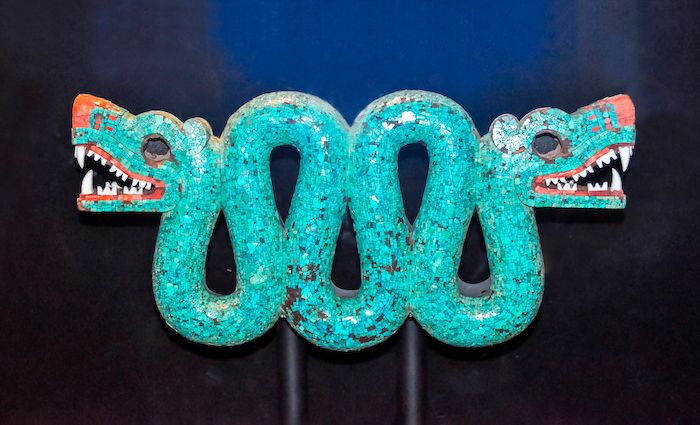

5. Aztec Serpent

Mosaic | Room 27

This brightly colored artifact, dating back to about A.D. 1500, comes from the heart of the Aztec Empire. This two-headed snake is a symbolic relic of a powerful, artistic, and deeply complex nation.

The serpent lays flat and the inside is hollow, so it was probably a ceremonial necklace. We can perhaps imagine a high-ranking priest or nobleman wearing it was part of an elaborate costume that included feathers, gold, turquoise capes, and jewelry.

There is a snake carving in Spanish cedar with right red pieces along the jawlines and the snout are oyster shells. The serpent’s teeth are made from conch shells and tiny holes suggest that a tongue might have extended out of each mouth.

The snake as a symbol

For the Aztecs, the snake possessed power. It represented a bridge between the earthly realm and other worlds. It symbolized fertility, and in its movement, echoed the ripples of water.

The Aztecs sourced precious materials from the far corners of their empire. The turquoise was highly prized and came from mines in the present-day American southwest. The gold and shells were also precious. Perhaps they were tribute from a conquered people or traded in one of the bustling markets in the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan.

Where did the museum get this one?

We’re not sure whether this piece came to Europe by way of Cortez and his marauding Spanish expedition. We do know, however, that it was certainly treasured by the empire that created it and valued by the subsequent conquering empires that acquired it.

The British Museum purchased the two-headed serpent from a dealer for 100 pounds in 1894.

4. Ife Head

Discovered 1939, Nigeria | Room 25

Quite simply, Ife Head changed the world. It offered an introduction to the highly sophisticated Yoruba people of Africa, a civilization that was creating art as refined as ancient Greece or Rome centuries before European colonization.

Up until this point, scholars dismissed sub-Saharan Africa, falsely assuming it was devoid of large civilizations that made contributions to art and culture. Ife Head provided a key to understanding a vast African kingdom that left no written records and scant evidence of its unquestionable power and reach.

The Ife Head shows us that the Yoruba empire stretched far enough to trade along the Mediterranean and even into Europe. The techniques they demonstrated in creating Ife Head were complex and probably introduced centuries before through an intricate trade system.

We are not sure who the Ife Head represents. However, perhaps it is not the “who” that is important. Nigerian poet, Ben Okri, explains, “this is not just ‘this is what a certain person or a certain king looked like’—it’s more than that. This is kingship in its ritual aspect, this is kingship in its relationship with divinity, this is kingship in relationship with the centrality of the myths of a tribe and of a people. This is kingship as an embodiment of the mysterious power of a people.”

As a form of art, Ife Head allowed Africa to take its correct place in the broad cultural and artistic understanding of the history of the world. It is impossible to overstate its role in shining a bright light on the accomplishments of the Yoruba.

Repatriating African Art

The Ife Head is part of the British Museum’s vast collection of over 73,000 pieces of Sub-Saharan African art. There are international calls to repatriate this piece from The British Museum, but the museum believes it owns the art outright.

3. Assyrian Lion Hunt Reliefs

Assyria 668 B.C. | Room 10

These reliefs decorated the massive palace complex of King Ashurbanipal, who ruled ancient Assyria from 668 B.C. to 631 B.C. Essentially an early Instagram account, these panels dictated a narrative. They showed exactly and only what the King wanted to show: bravery and power.

In Assyria’s easiest times, lions were a real problem. They roamed freely, attacked livestock and people, harassed herdsmen, and even stopped traffic on busy roadways. The Assyrian king would go on dangerous lion hunts to protect his people. In doing so, he showed that he was the victor against all things wild and brutal threatening his flock.

Building his brand

A long lineage of Assyrian kings fought wild lions and conquered faraway lands. They proved themselves in battle, became legends in their culture, and built an empire. King Ashurbanipal, however, ruled in a time of relative peace. He didn’t have opportunities to conquer enemies or march into war. Instead, he staged lion fights.

In a brilliant PR move, he built his own legacy. Beautiful palaces decorated with reliefs helped support his story. They helped bolster his own self-confidence, and perhaps, made an argument to the gods that he was a worthy ruler.

When King Ashurbanipal decorated his palace with these reliefs, he was championing his own might. He writes, “I Ashurbanipal, king of the world, king of Assyria, while carrying out my princely sport, seized a lion that was born in the steppe by its tail and, through the command of the gods [….] shattered its skull with the mace that was in my hand.”

And yet, as we view panel after panel of lion hunts, it begins to dawn on us that this work of art is about more than just this king and this lion. This is a perpetual duel between man and nature, an epic battle between the kings of beasts and kings of civilizations. We see that these are worthy opponents and one cannot exist without the other.

More poetry

Nineteenth-century American poet William Carlos Williams memorializes these reliefs in his poem, “March,”

“See!

Ashur-ban-i-pal,

the archer king, on horse-back,

in blue and yellow enamel!

withdrawn bow — facing lions

standing on their hind legs,

fangs bared, his shafts

bristling in their necks!”

Are there Assyrians who want their reliefs back?

Assyria, modern-day Iraq, continues to try and collect the items looted and stolen during the past twenty years of war and unrest. It is interesting to note that these reliefs were discovered by Iraqi archeologist, Hormuzd Rassam. A native of Mosul, he served as British Vice-Consul and was a champion of Iraqi culture and art.

2. Sutton Hoo Ship Burial

Discovered Sutton Hoo, Suffolk 1939 | Anglo-Saxon | Room 41

The Sutton Hoo site, always a crowd-pleaser, rose to even higher pop culture fame with the recent film, “The Dig,” starring Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan. The film shows the dramatic and unexpected discovery of an intact Anglo-Saxon burial ship in the quiet countryside of East Anglia.

It adds a few flourishes for drama, but the story is fascinating and incredibly just as it happened. It all began with Edith Pretty, who owned Sutton Hoo House in the southeast corner of England. Fascinated by the 18 mounds that dotted the property, she would dream of an Anglo-Saxon warrior king on horseback.

Turns out one of the mounds was hiding a massive Viking burial ship. Almost overnight, the Sutton Hoo Anglo-Saxon ship became one of the most important finds ever unearthed in Britain.

Shining a bright light on the Anglo-Saxons

The site, full of musical instruments, cauldrons, drinking horns, weapons, gold and silver, skins and furs, transported us back in time to Beowulf. A world that was dark and obscure came to life.

The identity of the man buried in the ship remains a mystery. King Raedwald, Anglo-Saxon King of East Anglia, is the most compelling candidate. Whomever he was, he was powerful and beloved enough for a community to drag a wooden ship up from the river and collect a treasure of untold value for his burial.

The trove of treasure includes the famous helmet, reassembled from 500 pieces. The helmet’s intricate metalworking depicts mythological dragons, warriors, and serpents. The rows of garnets that line the eyebrows would glint in the firelight.

The find at Sutton Hoo shows us how interconnected eastern England was to Scandinavia, but also to the larger world. Artifacts include coins from France, bowls with Celtic design, silver spoons that suggest interaction with Christianity, silver from Byzantium, and those garnets that were probably from the Asian sub-continent. Here, in a small corner of East Anglia, was the final resting place of a commander of a great civilization.

Who technically owned this treasure?

England has complex laws concerning found “treasure troves,” which are often claimed by the king. After all, they often once belonged to a king. An inquest asserted, however, that the treasure at Sutton Hoo belonged to Edith Pretty and could not be commandeered by the British Museum. She donated all of the findings to the museum anyway, within days of the inquest.

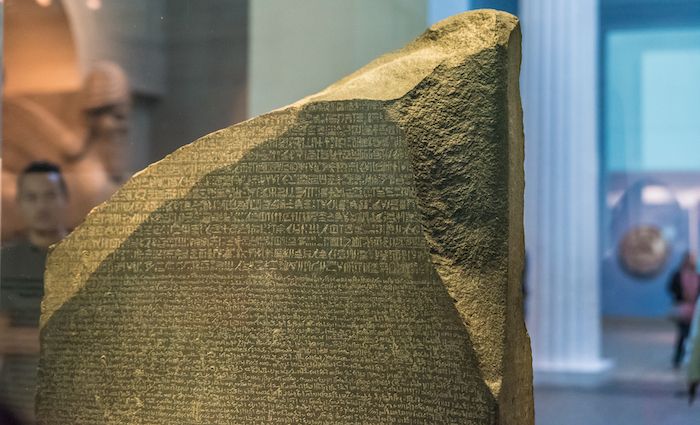

1. The Rosetta Stone

Ptolemy V | Egypt | 196 B.C. | Room 4

Napoleon, eager to follow in the footsteps of Alexander the Great, marched thousands of soldiers across the Egyptian desert. The entire expedition, however, was a massive failure. Napoleon left after just one year, sneaking away in the night. Half of his soldiers died and those who survived suffered serious illness and desert blindness.

The British sank their ships and the Ottomans ejected them from Egypt after an unconditional surrender. During this short-lived invasion, the French were repairing Fort Julien in Rosetta when they found a stone with numerous inscriptions.

The French and British squabble like children

The French knew immediately that this massive stone was something special; even Napoleon took time to inspect it. It appeared that the inscription was in three languages: hieroglyphics, Demotic, and ancient Greek.

During the negotiations for their surrender to the British and Ottomans, the French tried desperately to keep the stone, arguing it was personal property. The British, however, loaded it up with all of the other spoils looted by the French and took it to London.

The stone was an immediate celebrity; the British Museum made copies and rubbings and sent them around Europe. Thus began an international race to solve the mystery and decipher the hieroglyphics. Intellectuals jostled for prominence and published attempted translations; there was backbiting, lying, falsifying information, libel—everything short of violence.

It took 23 years. Finally, a French fellow, Jean-Francois Champollion, solved the thousands-year-old riddle of hieroglyphics. In doing so, he beat out dozens of scholars, including famed Brit, Thomas Young.

So, what did it say?

The text of the Rosetta Stone is as mundane a decree as you can find. A bureaucratic statement issued in Memphis in 196 B.C., it proclaimed Ptolemy V as ruler of ancient Egypt.

Because the stone recorded the decree in three languages, it was invaluable. The key for Champollion was the cartouche—a series of hieroglyphs that spelled out Ptolemy’s name. He used this, along with the cartouche of Ptolemy V’s wife Cleopatra (not that Cleopatra), to crack the code.

The Rosetta Stone is important. It was the key to solving a mystery that had puzzled the world for thousands of years. However, it is also a large, very heavy symbol of past empires trampling on one another for power and legacy.

Are we all Walter White?

In conclusion, the story pieced together at the British Museum is really a pattern. Each empire fights, conquers, builds, creates art, sits smugly in superiority, falls, and is lost to time. Each one is Shelley’s Ozymandias:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our best London tours to take and why.