Planning to improve your knowledge of modern art by admiring Antoni Gaudí‘s most famous buildings and works of art but unsure where to start? Well, you’re in the right place since we know where to find his most impressive works of architecture. Here are the most famous buildings by Gaudí that you should plan to see!

The Most Iconic Structures and Artwork by Antoni Gaudí

Before we learn about the architecture, it is important to understand the artist. So, let’s talk briefly about Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí, who was was born in 1852 in Reus (Cataluña). He qualified as an architect in 1878 and started working on many recognizable projects around Barcelona and Spain.

Moreover, Gaudí received the patronage of the Güell family, who was one of the driving forces behind Catalan industry and economy. This relationship built in a strong admiration for Catalan culture will be crucial for Gaudí’s success and legacy as an artist.

Gaudí established himself as an innovative architect (and even artist) and that means his style is often difficult to define or even understand. It also makes his art quite interesting. According to Britannica, he died early in 1926 when a tram hit him while walking not far from La Sagrada Família in Barcelona—his greatest masterpiece.

As an elderly man, Gaudí became incredibly insular and let himself go. Unfortunately, this meant that he looked like a beggar when the accident happened, so no one came to his aid. As a result, he was eventually taken to a hospital for the poor where he died unidentified and alone. His remains lie in the crypt at La Sagrada Família in honor of his accomplishments.

11. Bellesguard

1900-09 | Modernist Manor House | Barcelona (Cataluña)

This church is also known as Casa Figueres, due to the name of its owner in the 20th century: Jaume Figueres. Jaume had been a great admirer of Gaudí, so when he died, his wife María commissioned this work on his behalf. This Gaudí building is located in a district of Barcelona, from which you get an amazing view of the city. In fact, the name “bellesguard” means beautiful sight.

According to author Hugo Kliczkowski, the land on which Bellesguard was built used to belong to the royalty of Barcelona until the 15th century. Therefore, Gaudí wanted to bring that medieval aesthetic to the design. He also respected the few archaeological remains dotted across the landscape.

The materials used are nothing terribly special—just brick and stone. But of the entire building, the most remarkable feature that makes this a popular site is the tower: Torre Bellesguard.

In addition, the interior design of the property follows a more modernist style instead of the neogothic aesthetic of the façade of the building. According to Carles Rius, Gaudí might have start experimenting with some of the geometric elements popular in his aesthetic at Bellesguard, as a practice run for what he did at Sagrada Família.

Location: Bellesguard

10. Episcopal Palace in Astorga

1889-1913 | Catalan Modernisme Palace | Astorga (Castilla y León)

According to authors Cristina Montes and Aurora Cuito, this palace was a problematic project from the beginning. The previous episcopal palace suffered from fire damage, so then-bishop Joan Baptista Grau i Vallespinos commissioned the new palace construction to Gaudí.

Although the bishop loved the concepts, the episcopal committee in Madrid most certainly didn’t. Since they had to approve every aspect of this project, it was a constant battle.

Kliczkowski, Montes, and Cuito also agree that Gaudí ended up creating a more modern building that resembled a medieval fortress, with many gothic elements which were characteristic of his architectural style. Furthermore, the use of stone from the region of El Bierzo (local to Astorga) helped it harmonize with the general landscape of the city.

After the bishop died, Gaudí quit the project since he found it impossible to liaise with the episcopal council without his patron and advocate. Eventually, Ricardo Garcia Guereta finished the building in 1913, as noted by the official Antoni Gaudi website.

The more recent history of this building is not as religiously connected. During the Spanish Civil War, it became the headquarters for the Francoist party la Falange. And nowadays, it is a museum about El Camino de Santiago.

Location: Episcopal Palace

9. Casa Botines

1891-92 | Modernist Building | León (Castilla y León)

This is one of the few examples of Gaudí’s work that you can see outside of Barcelona and Cataluña. Located in the city centre of León, the building is currently a museum about Gaudí, art, and the building itself.

Casa Botines stands supreme in the otherwise traditionally Castilian look of the city. Nonetheless, the artist borrowed from the city’s medieval past and gave the building and overall neogothic aesthetic.

However, according to Jeremy Roe, the thing that brought Gaudí to León was the patrons of this building: Simón Fernández and Mariano Andrés who were Catalan merchants. The need to express their Catalan identity is clearly represented by the statue of St. George (patron saint of Catalunya), right above the main entrance to the building.

Roe also notes how interesting the building is since Casa Botines is not just a residential space. Two floors were apartments, but the ground floor and basement served commercial purposes for Simón and Mariano’s textile business. This building is worth visiting as it shows instances of the complex Spanish social panorama of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Location: Casa Botines

8. El Capricho (Villa Quijano)

1883-85 | Modernist Rural Villa | Comillas (Cantabria)

El Capricho is one of just two houses that Gaudí made in the countryside of Spain. Moreover, it is one of his oldest artworks. According to historians Garcia i Aranzueque and Montes, the owner of this property (Máximo Diaz Quijano) wanted Gaudí to create a house suited for his bachelor lifestyle. This seemingly whimsical approach to the project is what gave Villa Quijano its most well-known pseudonym of El Capricho (The Whim).

Furthermore, they argue that it is at El Capricho, where we start seeing Gaudí’s preference for curved lines and his use of orientalism combined with medievalism. In fact, a lot of people compare the tower to a minaret.

Moreover, it showed his dedication to his projects. For example, he took the lifestyle of his client into consideration in addition to the cold and rainy climate of Cantabria, plus its rural environment. Finally, Roe also suggests that El Capricho is important in Gaudí’s career since he also designed the garden. Its design would serve as a foundation for future Parc Güell.

Location: El Capricho de Gaudí

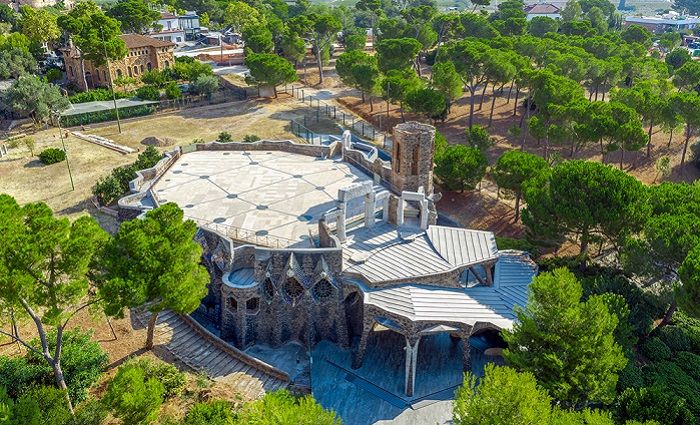

7. Colònia Güell

1898-1914 | Catalan Modernisme Building Complex | Santa Coloma de Cervelló (Cataluña)

Although he never completed this project, it is perhaps one of the most interesting ones of his works. Historian Jeremy Roe notes that the construction started in 1908, but in 1914 the patron Eusebi Güell died, so the project ended. Interestingly enough, the actual planning and design of the complex itself started almost a decade before its construction.

The purpose of this building was to house the workers from a factory that Eusebi Güell owned near this area. This was actually a pioneering enterprise for both Güell and Gaudí. Gaudí used nature as inspiration to develop this complex, which he envisioned as being organic and fluid, and developed some of his most famous techniques here.

Those techniques include the catenary arches, curved walls, and vaults, as well as his decorative broken mosaic tiling, known as trencadís. However, the most celebrated part of this complex is the crypt.

According to Roe, its shape resembles a tortoiseshell from the outside. But from inside, Roe states that it resembles more of the twisted skeleton of a snake. The crypt is so iconic that it made it to the UNESCO World Heritage list along with many other works by Gaudí.

Location: Colònia Güell

6. Casa Vicens

1878-1885 | Modernist Building | Barcelona (Cataluña)

This was Gaudí’s first domestic property and arguably his first “important” project. This is a rather imposing building with four stories. Author Jeremy Roe notes that Gaudí had already started the designs for this house in the late 1870s, though construction didn’t start until 1883. This is also the same period when he was working at El Capricho.

You can see the similarities between the two buildings with the use of ceramic cladding. The colourful and striking façade is one of the reasons why this is one of Gaudí’s most famous buildings and has caused sensation since the late 19th century.

Interestingly, straight lines are common in this building, despite his preference for curves which appear more prominently in some of his later works. Another reason this building is rather famous is partly thanks to the richness of its interior decoration. One of the best examples for admiring the interior design work is the smoking room.

This attention to interior detail shows that Gaudí was more than an architect. He was also a great designer and artist. Moreover, from an architectural standpoint, Roe highlights that this building shows well Gaudí’s mastery of orientalism as a form of art and architectural composition.

In particular, it seems that this was Gaudí’s interpretation of a Spanish art trend called neo-mudejar. This was a Moorish revival style popular during the 19th century in most of the Iberian peninsula. Allegedly, he took inspiration straight from the famous Alhambra Palace in Granada, and you can read about that palace here.

Location: Casa Vicens

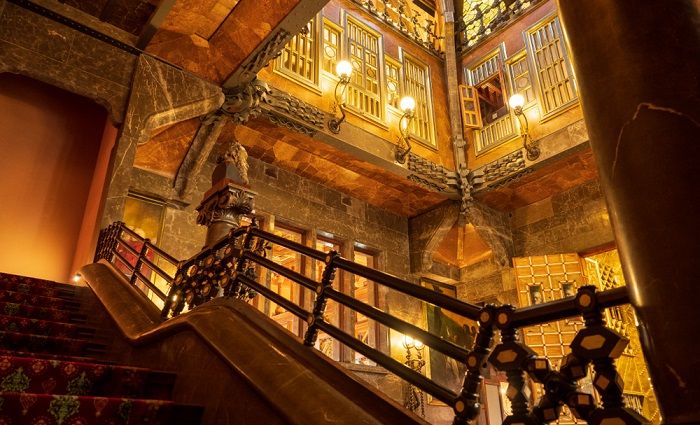

5. Palau Güell

1886-1890 | Catalan Modernisme Mansion | Barcelona (Cataluña)

Movie buffs may appreciate the following fact. Palau Güell actually appears in the film The Passenger starring Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider. It also happens to be another one of Gaudí’s UNESCO-designated buildings. According to Lluis Tolosa, the friendship between Gaudí and his patron and friend, Eusebio Güell, was crucial for the development of the artist, and it shows best in this building.

The evidence suggests they paid no heed to the budget and just delved into their wildest architectural fantasies for this project, changing plans up to 30 times! We know this from all the sketches Gaudi left us with. They originally designed the building to serve as a house where guests could also stay and even enjoy concerts in there. Some of the most famous features of this building are the iron works prominent all over the façade.

But the palace is most splendid inside and it shows Gaudí as an amazing interior designer. He used iron features in the interior as well, along with first quality materials such as hardwood, granite, and marble. If there was any doubt about how much money the Güell family had, I am confident you’ll understand when you step inside.

However, during the Spanish Civil War, it took a different role. According to LLuis Tolosa, it was seized from the Güell family and used to hold the barracks and the prison. Eventually, the family decided to donate it to the local authorities of Barcelona, who take care of it currently and use it as an example in the Modernisme routes of the city.

Location: Palau Güell

4. Casa Milà (La Pedrera)

1906-1912 | Catalan Modernisme Building | Barcelona (Cataluña)

Also known as La Pedrera (meaning the quarry), this was the last big project that Gaudí completed before his death. This building is also on the UNESCO World Heritage list, but what makes this building really special for historians like me is that we actually have a detailed account from the builder who worked with Gaudí on this project. His name was Josep Bayó, and thanks to him, we know a tremendous amount about this building and its history.

According to Juan Bassegoda Nonell, Gaudí envisioned an amazing project for his patron Pere Milà, who presented the architect with a huge piece of land in the Eixample (one of the most popular neighborhoods of Barcelona). The building received much criticism at the time as it did not match any of the styles of the area. In fact the name, “pedrera” suggests that people just saw it as a bunch of rubble.

Regardless of what his contemporaries may have thought, Gaudí performed some incredible innovations in this building. From an architectural standpoint, this huge structure of 1,323 square metres has an entirely self-supporting stone façade. That means there are no load-bearing walls! In addition, he put in as many windows of any dimension he wanted, so there is plenty of natural light.

But one of the most recognized elements of this building it the roof. Building on what he learned at Palau Güell, he filled the roof with shapes and figures, making it almost its own sculptural park on top of the building. You might also recognize it since other scenes from The Passenger were also filmed here, as well as a scene for Vicky Cristina Barcelona.

If you want to leave the planning to the experts, check out our Private Tour of Gaudí’s Casa Milà and Casa Batlló in Barcelona.

Location: Casa Milà

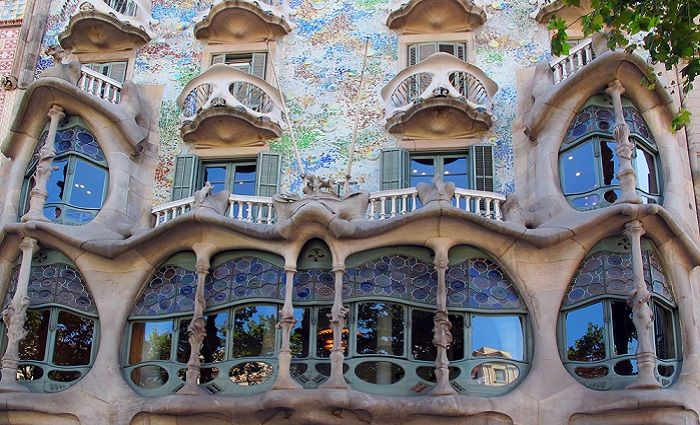

3. Casa Batlló

1904-06 | Catalan Modernisme Building | Barcelona (Cataluña)

This building is most famous for its façade, although Gaudí worked on other aspects of the property too. Locally, the house is known as La Casa dels Ossos: The house of bones. This is due to the visceral appearance of the façade. The decoration technique does have that bone quality that makes many people feel like it is—or was—part of a living creature.

Moreover, this is perhaps the most beautiful or effective use of the trencadis technique that we have seen in this list. In fact, almost the whole façade is covered in mosaic tiles, ranging from golden tones to blues.

According to Hugo Kliczkowski, the lighting effect on the façade as the sunlight hits it creates an iridescent effect which contributes to the wonder of this building. In addition, the balconies that dot the exterior of the building create contrast between the scaly textures and the bone aesthetic. You’ll also notice the roof tiles are arched, so it looks a little like a dragon or dinosaur!

If you want to leave the planning to the experts, check out our Private Tour of Gaudí’s Casa Milà and Casa Batlló in Barcelona.

Location: Casa Batlló

2. Parc Güell

1900-1914 | Catalan Modernisme Park | Barcelona (Cataluña)

This famous site is also on the UNESCO World Heritage list. Eusebi Güell also commissioned this to Gaudí, and according to Kliczkowski, Güell’s inspiration was English garden landscaping. Therefore, he decided to bring that style to the urban life of Barcelona and create a garden city. However, the project was deeply unsuccessful and turned into a public park in 1920s.

This project belongs to Gaudí’s naturalist phase. Everything that is man made in this park reflects the same feelings that nature would in a real park. According to Conrad Kent and Dennis Prindle, it is interesting that Gaudí managed to create such a “natural space” in an area where nature was very much lacking.

In fact, Parc Güell’s land used to be a pretty lifeless area—not far off from becoming a wasteland. Moreover, Marian Moffett, Michael Fazio, and Lawrence Wodehouse say this became the perfect playground for someone like this artist.

At Parc Güell, Gaudi combined natural forms with his imagination from ample staircases that look like flowing lava to oblique angles that create whimsical fairytale-like grottos. Finally, the trencadis technique becomes a wonderful use of colour everywhere in this complex. The different textures and materials used to create the different separate spaces in this park will transport you to a different world, and you will forget that you are in a rather busy city for just a moment.

Location: Parc Güell

1. La Sagrada Familia

1882-now | Catalan Modernisme Church | Barcelona (Cataluña)

La Sagrada Família is one of the most iconic monuments in Barcelona. Unfortunately, the building was never finished as Gaudí died in the middle of its construction in 1926. However, the city of Barcelona has taken on the task to continue the work of the artist based on his plans and sketches and they keep on working on this church that’s like no other in the world.

There are many reasons why this church is the best of Gaudí’s work. As you may have noticed, it seems that he always used previous projects to improve or test techniques that later appear fully fleshed in a different place. So, arguably, La Sagrada Família is the final piece of his architectural design puzzle.

From an architectural viewpoint, one of the most amazing aspects of this building is that it doesn’t have a single straight (or 90 degree) angle! It also has nine recognizable spires that are like the unique structures and chimneys Gaudí did for some of his other buildings—but exponentially bigger.

Finally, although the building is listed on the UNESCO World Heritage list, it is only the crypt and the Nativity façade that are part of the preserved structure. If you want to know the full story behind La Sagrada Família, read our article on it here.

Location: La Sagrada Família