The French consider Auguste Rodin the greatest French sculptor and when you visit the Musée Rodin, you’ll see why. This isn’t the largest museum you can visit in Paris, but knowing the most important pieces ahead of time is helpful. My list of the most famous artworks to see at the Musée Rodin will be your guide to understanding the creative genius of their maker.

Pro Tip: Heading to the Musée Rodin in Paris? Bookmark this post in your browser so you can easily find it when you’re in the museum. Check out our Paris Guide for more resources, our Paris Museum tours for a memorable visit, and read more about Auguste Rodin—the man behind the masterpieces.

What You Have to See at the Rodin Museum in Paris

The Musée Rodin opened in 1919, and you’ll find one of the prettiest gardens in the whole of Paris here. Rodin’s sculptures absolutely bring the garden to life. In harmony with nature, the sculptures seem to change as the light effects change from one season to the next. There are flowers blooming all year long here. It’s truly a magical place you’ll fall in love with when you come to visit.

This estate holds the most incredible pieces of art from the famous The Thinker toThe Kiss. In fact, you’ll find nearly 400 artworks made by Rodin in this hotel-turned-museum. (You’ll even find some Van Gogh here!) Before we dive into the top art at Musee Rodin, let’s get to know the artist a little better so you can appreciate his skill.

About Auguste Rodin

Many people in the art world saw Auguste Rodin as a radical. His contemporaries—formally-trained sculptors—were stuck in old-fashioned modes of art-making. Rodin’s sculpture was often rough and highly expressive rather than passive and polished.

French art historian and Rodin specialist Gilles Néret explains that Rodin rejected predictable, academic art. Surprisingly, he failed the entrance exam to the top Paris art school École des Beaux-Arts three times! Instead, he studied and developed at Petite École.

In 1916, the year before he died, Rodin bequeathed all of his possessions and works of art to the French state. In return, the state bought the 18th-century rococo-style mansion, the Hôtel Biron, where he was living and working. After his death, the government converted the building into a museum and dedicated it to Rodin.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out how to visit the Musée Rodin.

11. The Waltz by Camille Claudel

Camille Claudel | 1893 | Bronze | First Floor, Room 16

One of the most famous artist-and-muse relationships in the history of art was that of Rodin and Camille Claudel. The question is: Who was the artist and who was the muse? Both of them were artists and their relationship notoriously stormy.

Claudel was originally Rodin’s student, starting in 1884. She became his lover and they were embroiled in a passionate affair until 1898. Art historian Claudine Mitchell explains that, in the course of their relationship, the two artists explored their shared passion–sculpture.

For a number of years, it was an exchange between equals. In a kind of duet, they produced dramatic and superb depictions of the human figure in the very modern style you see here in this work and in the mature works of Rodin.

Tragically, Claudel never achieved the fame Rodin did. Claudel biographer Odile Ayral-Clause reveals that, when The Waltz was shown at the Salon National des Beaux-Arts (Fine Arts) in 1893, Salon officials criticized the piece for allegedly having a “violent sense of reality.”

Notice how the rough texture of the woman’s gown doesn’t emphasize the unfinished quality of the material. Rather, it suggests intense movement, as though the couple is spinning rapidly, almost floating in space.

It seems like they might easily topple over if not for the raised foot of the male, which seems to balance the couple. They are completely absorbed in one another and the dance. A gallery in the museum is devoted to Claudel’s work and heartbreaking biography.

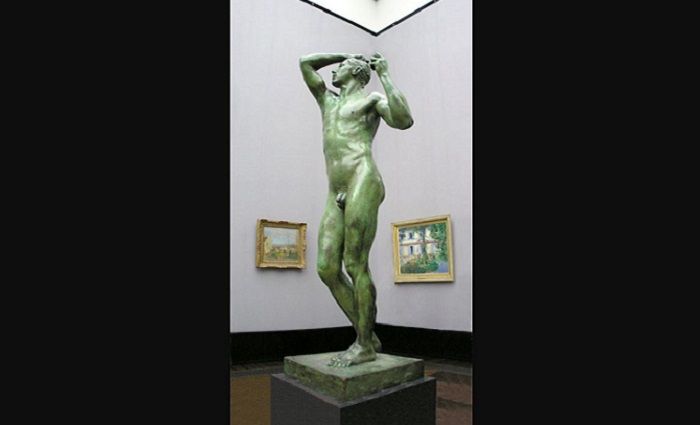

10. The Age of Bronze

Auguste Rodin | 1877 | Bronze | Ground Floor, Room 3

The Age of Bronze is an early sculpture in Rodin’s vast body of works. It is an example of the artist’s great skill in representing the human body realistically. Art historian and curator, Flavio Fergonzi, explained that Rodin idealized the body for two reasons: To link the sculpture to classical and Renaissance art and to show off, basically.

The concept of virtuosity (keen interest in unique art) was popular during the Renaissance. Artists demonstrated their expert skills by creating breathtakingly life-like figures. That’s precisely what Rodin was doing with The Age of Bronze, though it was created long after the famed Italian Renaissance era.

According to Néret, Rodin produced this artwork in Brussels, Belgium. A handsome, young Belgian soldier named Auguste Ney was his model. When the artist exhibited the sculpture at the important Paris exhibition, the Salon, in 1877 it caused an uproar.

People wondered what was going on with this mysterious, nude man and his raised arm. Rodin had originally put a spear in his hand so he’d look like an ancient warrior but then changed his mind. Some people accused him of making a cast from a model since the figure is so realistic but that wasn’t the case. Rodin was just very, very good.

There’s nothing like a good scandal to potentially make someone famous and that’s basically what happened for Rodin. He received the commission to produce The Gates of Hell in 1880, probably due to the attention he got with The Age of Bronze.

9. The Cathedral

Auguste Rodin | 1908 | Stone | First Floor, Room 10

Remember the children’s rhyme to which you link your fingers and make a church with a steeple? Rodin basically did that with his sculpture, The Cathedral.

According to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (where you’ll find an authentic copy), Rodin’s book The Cathedrals of France may have been one of the important inspirations for this sculpture. Moreover, his tours of some of the great Gothic cathedrals of France in 1910 and 1911 inspired the book. It included drawings he made while visiting many beautiful churches.

The visible carving marks on the sculpture are common to most of Rodin’s art besides his earlier works. Eventually, Rodin decided that it was less important to show off his skill with realism than to produce art that expressed emotion and ideas.

Retaining the tool marks and leaving parts of his sculptures somewhat rough was the most modern thing Rodin could have done at that time. For this reason, art historians and critics thought of him as the first truly modern sculptor.

Look closely and you’ll notice that the elegant hands of The Cathedral are both right hands. Catherine Lampert, another authority on Rodin, notes that the hands originated with two different sculptures of human figures. Rodin modeled the hands and then copied them for this work. The fingers that gently touch from the two hands do remind one of the buttresses and pointed arches of a Gothic cathedral.

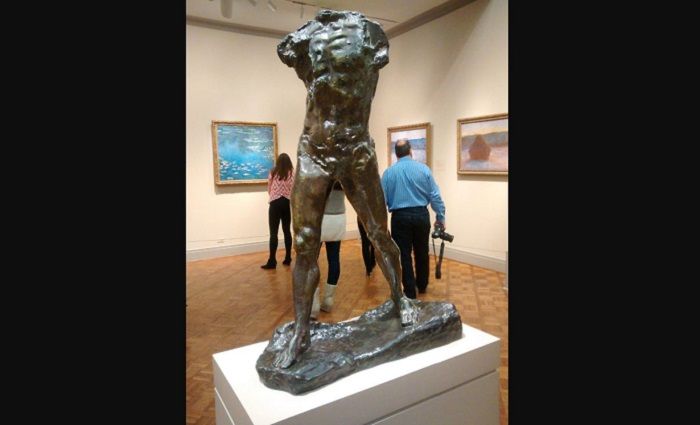

8. The Walking Man

The Walking Man | 1907 | Bronze | First Floor, Room 17

You might be wondering what’s so special about this particular sculpture. After all, there’s no shortage of sculptures of standing nude men. Rodin wanted it to seem like the figure was striding forward. This gesture—one foot forward—actually marked a major turning point in the history of art, centuries before Rodin’s portrayal.

If you think about really ancient sculptures, a lot of the human figures look pretty frozen and stiff, right? Eventually, artists improved their representations of humans to make them look more lively and even in motion. The earliest attempts at doing so by the ancient Greeks and Egyptians involved depicting one foot extended at least a few inches forward from the other—sometimes with a swinging arm.

Rodin knew all of that when he created The Walking Man. The sculpture is, in part, a tribute to a long line of sculptors that came before him. Néret points out that it is also a demonstration of his creative process. Rodin often rethought and reworked his sculptures. Poses could change. He would remove one figure from a group. Or, he might depict an entire body or, conversely, only a torso.

The Walking Man was a reworking of Rodin’s Saint John the Baptist, also called First Impression, writes Néret. He used studies—sketches, drawings, and models in clay—to revise this piece. Pulling it all together wasn’t as easy or successful as Rodin might have hoped, though. The torso tilts forward and twists slightly toward the left, and you get the feeling he might tip over. With no arms to swing or balance himself, the idea this sculpture communicates is one of incompleteness or absence.

7. The Burghers of Calais

Auguste Rodin | 1884-89 | Bronze | Garden, NW Corner Near Rue de Varenne

You don’t even need to know the history behind Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais to be moved by it. According to Lampert, these six men dressed in simple robes were important citizens or “burghers” of the city of Calais in the 14th century. The English king, Edward III’s army, had laid siege to Calais during the Hundred Years’ War. They’d tried to hold out under the orders of their own king, Philip VI, but they were starving. So, these burghers offered their lives in exchange for an end to the siege.

Rodin captures the despairing but brave men walking together to their deaths, nooses already around their necks. According to a reliable historical account, the burghers weren’t executed after all. The wife of Edward III, a devout Christian, interceded on their behalf.

Rodin produced small models of the artwork. Eventually, Lampert explains, officials of Calais installed one of several life-size versions of the sculpture on a pedestal in Calais in 1895, which made Rodin unhappy. He wanted viewers to be able to walk around the figures and interact on a personal level.

Later, the city of Calais decided to move the sculpture to a spot on the ground level in front of the town hall. His signature, rough, unfinished-looking style makes this artwork by Rodin even more emotionally expressive. Heavy vertical lines create a sense of downward movement entirely in keeping with the heavy emotional theme of this artwork. The faces of the figures alone are intense psychological portraits.

Our Best Versailles and Paris Louvre Tours

Top-Rated Tour

Secrets of the Louvre Museum Tour with Mona Lisa

The Louvre is the largest art museum on Earth and the crowning jewel of Paris, which is why it’s on everyone’s bucket list. Don’t miss out on an incredible opportunity! Join a passionate guide for a tour of the most famous artwork at the Louvre. Skip-the-line admissions included.

See Prices

Likely to Sell Out

Ultimate Palace of Versailles Tour from Paris

Versailles isn’t that difficult to get to by train, but why stress over the logistics? Meet a local guide in central Paris who will purchase your train tickets and ensure you get off at the right stop. Then enjoy a guided tour of the palace and the unforgettable gardens. Skip-the-line admissions included to the palace and gardens.

See Prices

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our best Paris tours to take and why.

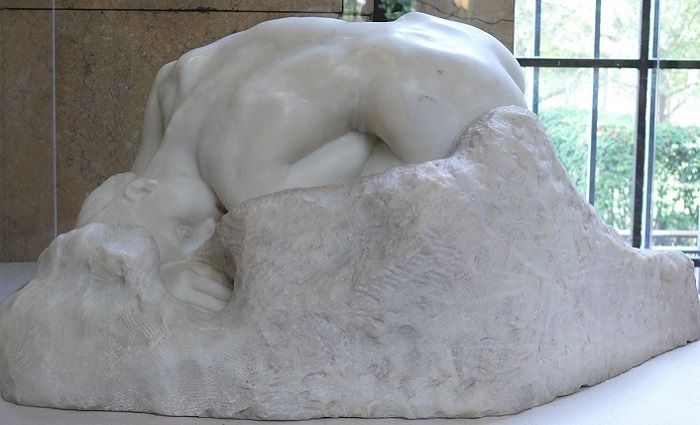

6. Danaïd

Auguste Rodin | 1889, Marble in 1890 | Marble | Ground Floor, Room 7

Yet another sculpture that didn’t make it to the final version of The Gates of Hell. Danaïd is a stunning example of the tenderness with which Rodin depicts the human figure. Rather than emphasizing the outward appearance of the woman, he focuses on feeling—deep feeling. This beautiful, solitary woman isn’t sleeping. Instead, Rodin portrays a profoundly emotional episode.

According to an ancient Greek myth, the daughters of King Danaos (the Danaïds) killed their husbands on their wedding night. As punishment, they were forced to fill a bottomless barrel with water for eternity.

This lonely Danaïd seems to have just despaired at the futility of her task. She has collapsed onto the rock beneath her and is nearly absorbed into it, trapped forever in her grief.

The poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, wrote that this tragic woman had laid her head down on her arm “like a huge sob.” Rilke described her flowing hair as “liquid”—an apt description. He was deeply moved by this artwork, which he saw as a testament to Rodin’s mastery at producing emotionally expressive works.

5. Monument to Balzac

Auguste Rodin | 1892-97 | Bronze | Garden, West of The Thinker, Near Boulevard des Invalides.

Honoré de Balzac, the esteemed French writer and poet known for his Realist style, died in 1850. Rodin, who was born in 1840, never met him, but the devotion he showed to the production of this sculpture suggests a profound admiration.

Néret described the complicated process involving the commission for this important monument. Apparently, the Society of People of Letters in Paris in 1891 hired Rodin to produce a monument to the great writer. In 1898, he displayed a full-size plaster model of it at the Salon in the Champ de Mars–just a stone’s throw from the present-day Musée Rodin.

Rodin was trying to capture the persona of Balzac rather than a physical likeness. The Society rejected the plaster model, reveals Néret, deeming it too rough and overly dramatic. The truth is, it didn’t look like Balzac but Rodin believed it captured his spirit. Plenty of people agreed, including the well-known art critic and historian, Kenneth Clark, who referred to this monument to Balzac as “the greatest piece of sculpture of the nineteenth century.”

According to Néret, it wasn’t until July 2, 1939, more than two decades after Rodin’s death, that the statue was finally cast in bronze. It was installed at the intersection of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and Boulevard Raspail in the 6th arrondissement only a short walk from the Metro stop, Vavin (line 4). There are now several bronze casts, including the one that graces the garden at the Musée Rodin.

4. The Three Shades

Auguste Rodin | Before 1886 | Bronze | Ground Floor, Room 5

You might be surprised to learn that the three nude male figures in this sculptural group are identical to one another! Each figure was cast separately from the same mold, rotated, and then joined by a common base. They are small versions of a monumental depiction of Adam, which was supposed to be placed on one side of The Gates of Hell, notes Néret. However, in the final version, the artist decided to relocate this group above the lintel in the center.

The group is meant to be interpreted as a personification of the dead. In Dante’s Inferno, the Shades hovered at the entrance to Hell. They were the souls of the damned.

This method of repeating the same drawing or sculpture of a human figure is an ancient one, which was taken up again by Italian Renaissance artists. You’ll often see a female version of this motif in drawings, paintings, and sculptures, called The Three Graces.

An expert could easily tell you that this version of The Three Shades is a modern cast. That’s because the color, Lampert explains, a kind of chocolate brown, is indicative of a more recent process and material. Bronze sculptures cast before Rodin died in 1917 were usually patinated–dark or nearly black with green flecks from oxidation. The Thinker is an example of earlier bronze casting.

3. The Gates of Hell

Auguste Rodin | 1880-1917 | Bronze | Garden, NE Corner

This monumental artwork is the most complex that Rodin ever created. He created over 200 different human figures and groups in this piece and even the plaster model is a masterpiece. It illustrates a scene from Dante’s Inferno, the first book of the Divine Comedy. According to Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, who has written extensively about this complex sculpture, it is almost 20 feet high, 13 feet across, and over 3 feet deep. The 180 figures on it average about 6 inches tall.

According to Le Normand-Romain, Rodin received the commission from the French Directorate of Fine Arts in 1880. The Directorate wantedThe Gates to adorn the entrance to the Decorative Arts Museum. Unfortunately, the museum was never built.

Rodin aspired to exhibit the piece at the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris but that didn’t work out either. 1889 came and went and he was still working on The Gates, although he’d become frustrated and had moved on to work mostly on other sculptures. Finally, in 1890, he held a solo exhibition in Paris and displayed a fragmentary version of the work.

In total, he spent 37 years in the Hôtel Biron, now the Musée Rodin, creating the complex sculptural group. He only stopped completely when he died in 1917. You could say it was his life’s work.

Dante’s warning in the Inferno, “Abandon every hope, who enter here!” was a guiding force for Rodin to compel viewers to be deeply moved by the sculpture. It is a tour de force of motion and drama. Allow yourself to linger and be swept up in the different scenes.

Search for recognizable figures you’ll see elsewhere in the museum as separate artworks like The Thinker, The Kiss, and The Three Shades. Note that, while Dante definitely inspired this artwork, most of the characters originate from Rodin’s imagination or other literary sources. It is Rodin’s version of Dante’s Inferno.

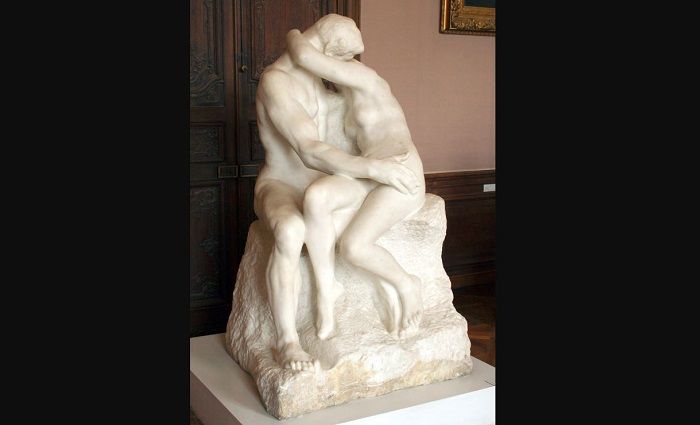

2. The Kiss

Auguste Rodin | 1882 | Marble | Ground Floor, Room 5

If not for the support of the government, many a French artist might actually have starved. Early in his career, as noted by Néret, Rodin was the very model of a struggling artist, but fortunately, the state hired Rodin to create a larger version of this world-famous, iconic sculpture. The Kiss found its way to the Musée Rodin in 1919 after sitting in the superb collection of artworks at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris since 1901.

The Divine Comedy was also the inspiration for this intimate depiction of two lovers who have completely shut out the world. The furiously jealous husband of Francesca has murdered Paolo and Francesca whom he caught kissing. The tragic lovers would roam forever through hell.

The problem was that these two don’t look distressed at all. Rodin agreed: There was nothing tortured about them. Instead, he designed a different group of figures to take their place on the Gates of Hell. Thus, Néret notes, The Kiss was born and first exhibited in 1887.

As far as the state commission was concerned, Rodin was busy with other projects like his Balzac. He didn’t get around to finishing the large marble version of The Kiss until 1898. According to Rodin specialist, Jacques Vilain, Rodin was not fond of the work. He saw it as overly sentimental and too polished and famously called it his “huge knick-knack.”

Feel free to disagree, however. Countless people all over the world find it beautiful, and you will too when you see it in person.

1. The Thinker

Auguste Rodin | 1903 | Bronze | Garden, Between the Gift Shop and the Museum

Rodin originally designed The Thinker to be part of The Gates of Hell too, and you’ll see a bronze version of it at the Musée Rodin. You can also see the plaster model at the nearby Musée d’Orsay. The original title of The Thinker was The Poet. He positioned the smaller, enigmatic, ruminating male figure on the half-moon shaped space above the lintel of The Gates of Hell. The artist enlarged the work and exhibited it in 1904.

As Fergonzi demonstrated in an exhibition dedicated to the subject, Rodin admired Michelangelo above all others, for he was the great master of the Italian Renaissance. Both artists favored the human body above all else for subject matter.

You might compare Michelangelo’s famous David to Rodin’s The Thinker. How, you ask? Well, The Thinker contemplates mortality and immortality. David ponders the power of the mind over the body. There’s another significant Italian connection as well. Rodin’s Gates of Hell references the Italian poet, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

In fact, reveals Fergonzi, is a portrait of Dante himself, although Rodin wouldn’t have known what he looked like. Michelangelo had produced a similarly seated figure in his day, a portrait of the powerful banker and his artistic patron, Lorenzo de’ Medici.

There are a great number of bronze casts of The Thinker around the world. Here at Musée Rodin, rosebushes surround The Thinker in the late spring and summer. Probably the most poignant version of this sculpture is the one on the tomb of Rodin and his wife in the gardens of their home in Meudon, France.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our best Paris tours to take and why.

Where To Stay in Paris

With a city as magnificent as Paris, it can be hard to find the perfect hotel at the perfect price. Explore the best hotels and places to stay in these incredible neighborhoods in Paris.