Art is emotion. It’s the raw expression of an artist’s innermost thoughts and feelings, laid bare on canvas for the world to see—though few truly understand. If a painting doesn’t move you, it’s often because its story and historical context remain untold. That’s why guided tours are invaluable.

A great guide doesn’t just explain art; they bring it to life. You don’t need an art degree to feel the power of a masterpiece, but a skilled storyteller with deep expertise can transform your experience from passive observation to profound connection.

This article won’t replace a tour—it’s your foundation for making one unforgettable. Explore our Louvre tours and Paris tours led by the city’s most passionate guides, and prepare to see art in a whole new light.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if a Louvre Museums tour is worth it.

What is the rating scale of artwork? Simply put, the best art compells you to stare at it for a long time. The longer you’re compelled to stare, the better it is.

24. St. Francis of Assisi Receiving Stigmata

Giotto di Bondone | 1295 – 1300 | Tempura on Wood | Denon Wing, Room 708

Byzantine art: the artistic equivalent of a shrug.

If you’ve ever wondered what happens when creativity takes a centuries-long nap, look no further.

Stiff, lifeless figures with all the emotional range of a brick wall, awkward poses that scream “I’ve never seen a human body before,” and enough gold leaf to make a pharaoh blush.

It’s like someone decided art should be as unrelatable as possible and then doubled down.

If you’ve seen one Byzantine painting, congratulations—you’ve seen them all. And honestly, good riddance.

But then, like a beacon of hope in a sea of monotony, Giotto di Bondone shows up with St. Francis of Assisi Receiving Stigmata.

This isn’t the last gasp of Byzantine art—it’s the beginning of its funeral procession. Giotto does the unthinkable: he gives his figures life. They interact, they emote, they tell a story. It’s not just a painting; it’s a revolution in tempera on wood.

Stand in front of this piece in the Louvre’s Denon Wing, and you’ll see the difference immediately. Compare it to the other Byzantine works in the room, and it’s like stepping out of a black-and-white photo into full technicolor.

Giotto’s figures aren’t just standing there like cardboard cutouts—they’re alive, connected, and brimming with a spark of humanity. It’s subtle, but it’s the crack in the dam that would eventually unleash the Renaissance.

Giotto does something unthinkable for the period… he introduces figures with more emotion that interact with one another and tell a defined story. This theme would become the backbone of the Renaissance.

And Giotto didn’t stop there. He went on to fresco the Scrovegni Chapel, a masterpiece of color and storytelling that shoved art into a new era. Without Giotto, we might not have the Sistine Chapel, the Mona Lisa, or Las Meninas.

So while this painting might not be the flashiest in the Louvre, it’s first on my list because it marks the moment art woke up, stretched its legs, and decided to be extraordinary again.

23. The Rape of the Sabine Women

Nicolas Poussin | 1637-38 | Oil on Canvas | Richelieu Wing, Room 828

Nicolas Poussin: the Frenchman who wished he were Italian.

Born in Normandy, schooled in France, and then promptly packing his bags for Rome, Poussin spent most of his career basking in the Eternal City’s glory.

And honestly, who can blame him? Rome was the place to be if you wanted to paint grandiose scenes of abduction and chaos with a side of moral ambiguity.

Enter The Rape of the Sabine Women, one of the most infamous stories in Roman history—second only to the murder of Julius Caesar (because, let’s face it, stabbing a guy 23 times is hard to top).

Poussin’s rendition of this tale is a love letter to Rome, drenched in drama, movement, and enough Renaissance flair to make your head spin.

Here’s the gist: Rome had a woman problem. Specifically, they didn’t have enough of them. Nearby tribes weren’t exactly lining up to help out, fearing Rome’s growing power.

So what does Romulus, the first King of Rome, do? He throws a party. But not just any party—a trap disguised as a social gathering. On Romulus’s signal (he’s the guy in the red cape and gold armor, looking suspiciously smug), the Romans abduct the Sabine women to make them their wives. Romantic, right?

The Sabine women, as history tells it, would go on to birth the second generation of Romans, laying the foundation for what would become the longest-lasting empire in European history. But let’s not sugarcoat it: this empire began with a kidnapping spree.

The story is a testament to Roman pragmatism—if they needed something, they took it, and figured out the ethics later. Harsh? Sure. Effective? Undeniably.

Poussin captures this moral mess beautifully. His figures are dynamic, his composition is masterful, and the chaos is palpable. It’s Italian Renaissance drama at its finest, even if it’s painted by a Frenchman who just really, really wanted to be Roman.

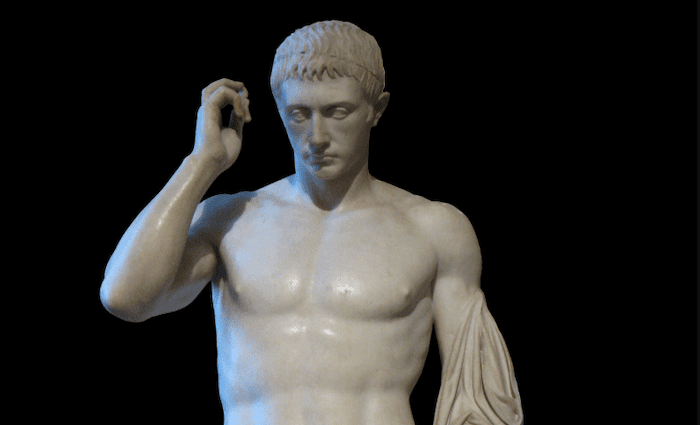

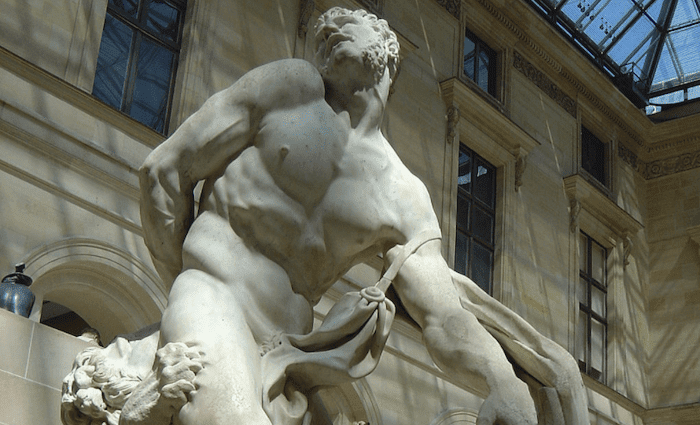

22. Marcellus Divinized into Mercury Psychopomp

Unknown | First Century B.C. | Dept. of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities

If we stopped making wine for a century, could we pick up where we left off, or would we have to start over? The same question applies to art.

The mastery we see today is the product of thousands of years of evolution. Art peaked in Greece during the 5th to 3rd centuries B.C. and again in Rome from the 1st century B.C. to the 3rd century A.D., only to fade into obscurity by the 6th century A.D. in Western Europe.

It wasn’t until Giotto di Bondone in the 13th century that art began its slow climb back, inspired by the lifelike forms of Ancient Rome.

The sculpture of Marcellus is a testament to the Roman mastery of the human form. His anatomy is so lifelike that his muscles appear soft, his shoulders natural, and his expression heartbreakingly sad.

It’s proof that Rome had artists on par with Michelangelo centuries earlier. Capturing such believability in marble is no small feat, and this sculpture stands as a reminder of the heights art once reached—and how long it took to reclaim them.

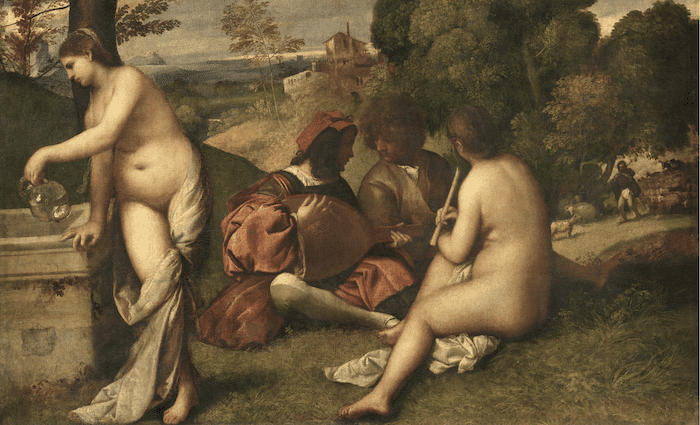

21. The Pastoral Concert

Titian | Oil on Canvas | 1509 | Denon Wing, Room 711

The Pastoral Concert is what happens when Renaissance art indulges in a fever dream.

Two clothed men sit in a pastoral landscape, while two nude women—figments of their imaginations—play a flute and pour water. It’s nonsensical, but in the 16th century, this was high art, not a bizarre hallucination.

The women are muses, symbols of inspiration and creativity. How do we know? Because they’re naked, holding a flute, and pouring water. These seemingly meaningless items they’re holding were visual clues of the time. As obvious “Bud Light” product placement in a cheap movie.

A flute meant music, water symbolized inspiration, and nudity… well, that was just the Renaissance being the Renaissance–these symbols were part of art parton’s vocabulary.

Let’s not overthink it: this is a fantasy. The women are idealized to absurdity, the supermodels of their day, conjured by the imaginations of the two men. Is it a celebration of artistic inspiration? A commentary on creativity? Or just an excuse to paint naked women in a field? Titian leaves it open to interpretation.

Whatever its meaning, The Pastoral Concert is a testament to the Renaissance’s ability to elevate even the most fantastical ideas into something profound. Whether you see it as a masterpiece or a glorified daydream, it demands attention—even if it leaves you scratching your head.

Like this article? These tours are for you!

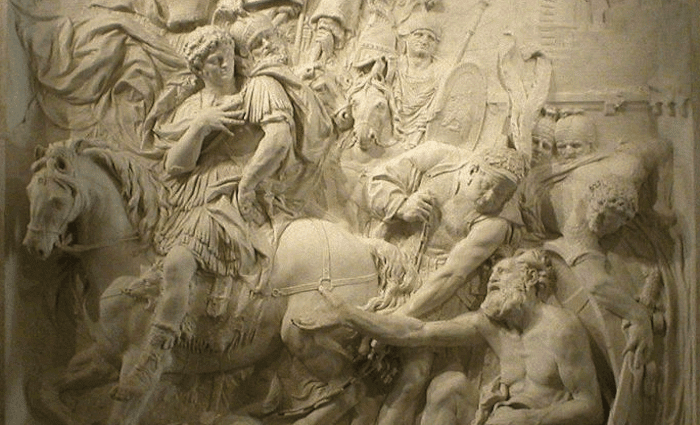

20. Alexander and Diogenes

Pierre Puget | Carrara Marble | Dept. of Sculptures, Royal Collection

Art experienced a revival in Florence during the 14th and 15th centuries before shifting to Rome under the patronage of the popes in the 15th through 17th centuries.

France, however, wouldn’t have its moment in art until the 18th century. Auguste Rodin, often hailed as France’s greatest sculptor and a father of modern art, didn’t emerge until the 19th century.

Before Rodin, Pierre Puget was arguably France’s first great Baroque sculptor who could rival the Italians.

One of his most notable works is a relief depicting Alexander the Great marching victoriously with his soldiers, overlooking the philosopher Diogenes begging on the ground. Alexander, portrayed as humble, pauses to acknowledge the philosopher, who famously despised wealth.

Ironically, this scene—intended as a ruler’s reminder to remain humble—was never presented to King Louis XIV. Instead, it was immediately placed in storage at the Louvre, a fate that seems to contradict its very message.

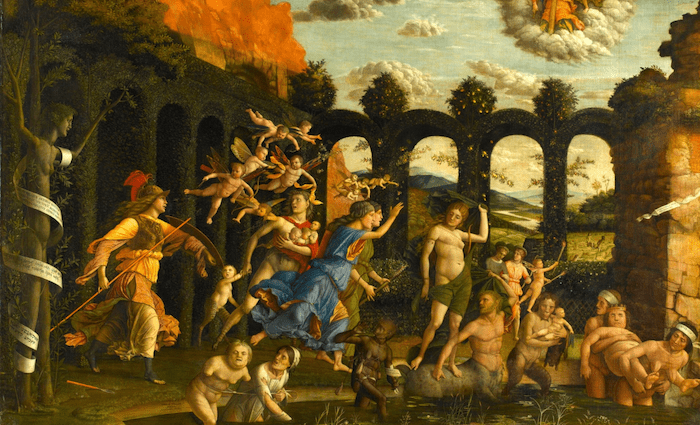

19. Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue

Andrea Mantegna | 1500-2 | Oil on Canvas | Dept of Paintings, Room 371

Andrea Mantegna’s Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue is an epic masterpiece brimming with symbolism and action, which is why it earns a spot on my list.

It’s a narrative painting—a story unfolding across the canvas with countless characters and layers of meaning. In other words, a tour guide’s dream, packed with scandal and intrigue.

You’ve likely read books or watched series like The Borgias that revel in the sexual pestilence of the Italian Renaissance’s noble families.

This painting, however, serves as a triumphant reminder that such desires were deemed “wrong” under the light of dogma and should be heroically expelled.

Sexual desire is just one of the many vices on trial here. On the lower right, three grotesque figures personify avarice, ingratitude, and ignorance. Two malformed men—one with breasts—carry a third crowned with stupidity and drunkenness. It’s a parade of vice, awkward and absurd.

Enter Minerva, spear in hand, rushing to expel these misshapen vices from the swampy courtyard—just in time to stop a centaur from raping Diana, the goddess of hunting and fertility.

The painting is a treasure trove of symbolism that reveals itself over time, like a fine wine. Hidden faces peer from the clouds, and Botticelli-like trees sprout human features. Every detail invites closer inspection.

Mantegna’s Venetian roots are unmistakable in the painting’s vibrant colors—Venice was known for its luminous palette. And if that weren’t impressive enough, Mantegna was over 70 years old when he completed this masterpiece. Keep an eye out for another bright Venetian work on this list.

18. The Virgin, Saint Anne, and the Child Playing with a Lamb

Leonardo da Vinci | Oil on Wood | 1503-19 | Denon Wing, Grand Galeriè 710 – 16

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin, Saint Anne, and the Child Playing with a Lamb is a technical tour de force, celebrated as one of his most complex works.

Pilgrims flocked to see it upon its completion, and they’ve been coming ever since, drawn by its intricacies.

To truly appreciate it, imagine yourself as a 16th-century observer, living in a world where art was the only way to visualize sacred figures like Saint Anne and the Virgin Mary.

In an era without photography or Google, da Vinci’s ability to personify these revered figures was nothing short of miraculous.

His attention to detail provided worshippers with a vivid, almost tangible connection to the divine—far superior to anything they could have imagined on their own.

The composition is a masterclass in geometry. Da Vinci arranged the figures in a triangular formation, guiding your eyes along its lines and holding your attention.

The gentle smiles of Anne and Mary radiate warmth and captivate the viewer, much like the enigmatic charm of the Mona Lisa.

While many would rank this painting higher, as a former tour guide, I believe the greatest works of art must offer more depth in the stories they tell and their impact on history. This is a masterpiece of technique and emotion, but it lacks the narrative weight of da Vinci’s most iconic works.

Nearby Da Vinci Works:

Fun fact: 25% of all Leonardo da Vinci paintings are in the Louvre Museum. Here are some others you should see nearby:

- Saint Anne, the Virgin, and the Child Playing with a Lamb

- La Belle Ferronière

- Portrait of Isabella d’Este (unfinished)

- Saint John the Baptist (particularly notable)

- La Giocanda (the Mona Lisa—listed below)

17. The Battle Between Love and Chastity

Perugino | 1505 | Oil on Canvas | Department of Paintings

The Battle Between Love and Chastity is an allegory of the internal struggle faced by our European ancestors: do you save yourself for a loveless marriage or embrace sexual freedom now?

Modern society no longer demands chastity before marriage, nor does it enforce arranged unions between strangers, making this painting feel distant from our reality.

Yet, for 15th- and 16th-century viewers, this was a deeply relatable conflict, one that shaped their lives and choices.

The artist, Pietro Perugino, may not be a household name, but his work graces the Sistine Chapel—though it’s overshadowed by Michelangelo’s Last Judgment and ceiling. Still, The Battle Between Love and Chastity is a beautiful and significant work in its own right.

This painting connects us to the moral and emotional struggles of the past, particularly the minds of women in the 16th century. It’s a window into a world where love, duty, and desire were at constant odds, and for that reason, it earns its place as one of the most important works in the Louvre.

Find Your Perfect Parisian Hotel

Hôtel de Seine ⭐⭐⭐

Saint-Germain-des-Prés • Period Décor

Excellent value for money, plus optional breakfast buffet and amenities for kids.

Hôtel Mayfair Paris ⭐⭐⭐⭐

1st Arrondissement • Fitness Center

Clean, cozy, and conveniently located near the Louvre.

Hôtel Villa d’Estrées ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Latin Quarter • Stylish and Spacious

Classic hotel within 5 minutes from Pont Neuf, Notre Dame, and Ile Saint Louise.

16. La Gioconda (Mona Lisa)

Leonardo da Vinci | Oil on Wood | 1503-5 | Denon Wing Room 711

In terms of pure fame, the Mona Lisa undoubtedly deserves the top spot on any list. But in terms of artistic importance? Eleventh feels like a fair compromise, and here’s why.

At its core, the Mona Lisa is simply a portrait. As an art form, portraits were never intended to achieve international fame—da Vinci himself would likely agree.

Yes, it may be one of the greatest portraits ever painted, rivaling Raphael’s Girl Holding a Unicorn and surpassing Gainsborough’s Blue Boy, but it remains just that: a portrait.

Portraits serve a purpose—to preserve the image of a person for posterity. The Mona Lisa only gained its legendary status after it was stolen in the early 20th century by an Italian janitor who claimed to be “returning” it to Florence.

Ironically, the painting was already at home in France, having been acquired by King Francis I in 1518—long before Napoleon’s infamous looting of Italian art.

The theft catapulted the Mona Lisa to international fame, not because it was da Vinci’s best work, but because it was one of the few surviving pieces by the maestro. When it was recovered and returned to the Louvre, the world couldn’t resist the allure of a stolen masterpiece. The painting became a sensation, more for its story than its substance.

While the Mona Lisa is undeniably a technical marvel—her enigmatic smile, the sfumato technique, the atmospheric background—it lacks the narrative depth or historical impact of da Vinci’s other works. If Michelangelo could visit the Louvre today, he would likely turn his back on La Gioconda and admire Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana.

It’s a masterpiece, yes, but not the greatest artwork in the Louvre. Its fame is a product of circumstance, not intention, and for that reason, it lands here at #11.

15. Milo of Croton

Pierre Puget | Carrara Marble | Dept. of Sculptures, Royal Collection

Another masterpiece by Pierre Puget, Milo of Croton, tells the tragic tale of an athlete—possibly a narcissist—who attempted to test his strength by splitting a tree trunk with his bare hands.

Trapped by the tree, he was unable to free himself and was ultimately devoured by a lion.

Puget’s work often carried a subtle critique of arrogance, perhaps reflecting his own self-awareness or a wish for humility in those who commissioned his art.

Humility, a value cherished by the ancients, was something Puget likely absorbed from the Baroque masters in Italy.

Puget is credited with sparking a French Baroque movement known as “Classicism,” marking the moment art began to shift north from Italy.

While there’s some truth to this claim, artists like Antonio Canova of the 18th and 19th centuries might argue otherwise. Stay tuned for more on that!

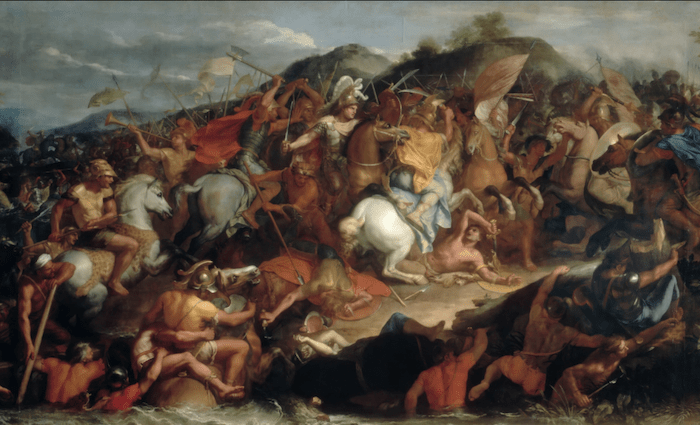

14. “The Battles” of the Granicus River

Charles Le Brun | Oil on Canvas | Dept. of Paintings, Louis XIV Collection

Charles Le Brun, the favored painter of King Louis XIV, was commissioned to create four monumental paintings, including The Battle of the Granicus River.

Standing before this masterpiece, I was immediately reminded of Raphael’s Battle of the Milvian Bridge fresco in the Room of Constantine at the Vatican. The resemblance is striking—and intentional.

Louis XIV, ever the competitor, sought to rival Italy’s artistic dominance. These paintings were his answer to the grandeur of the Vatican, a declaration that France could match, if not surpass, the artistic achievements of Rome.

Le Brun delivered exactly what the Sun King wanted: epic, detailed, and gloriously dramatic depictions of Alexander the Great’s victories.The Battle of the Granicus River is a testament to Louis XIV’s ambition and Le Brun’s skill. It’s not just a painting; it’s propaganda on a grand scale, aligning the Sun King with one of history’s greatest conquerors.

The parallels between Alexander and Louis XIV are impossible to miss—both men saw themselves as destined for greatness, and both used art to cement their legacies.

While it may not have the fame of Raphael’s work, The Battle of the Granicus River holds its own as a masterpiece of French Baroque art. Its placement at #10 reflects its historical importance and the sheer audacity of its creation.

It’s a painting that demands attention, not just for its artistry, but for the story it tells about power, ambition, and the eternal rivalry between France and Italy.

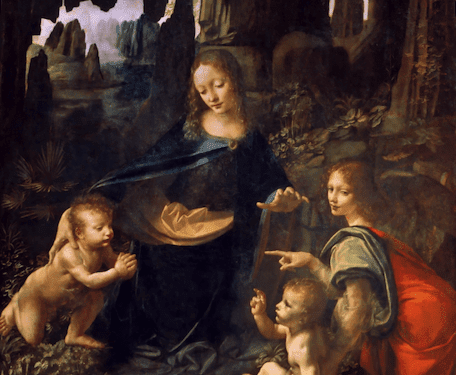

13. The Virgin of the Rocks

Leonardo da Vinci | Oil on Wood | 1483-86

The Virgin Mary sits among “rocks” with three other figures—hence the name. To her right (our left) is John the Baptist, kneeling under her protective arm.

Across from John is the angel Uriel, the “fourth Archangel” in Eastern Christianity, pointing directly at him. Below Uriel is Christ as a baby.

This painting, in my view, is second only to da Vinci’s Last Supper, and here’s why. First, there’s a nearly identical version in London with key differences—Uriel’s finger isn’t extended, and the colors vary.

It’s a small detail, but consider the controversy over Judas’ extended finger in The Last Supper. Da Vinci knew the power of subtle gestures.

Second, the composition is masterful. The figures form a triangular flow, guiding your eyes from Uriel’s hand to John, to Mary, and back again. It’s a visual loop that keeps you engaged.

Third, the soft, lifelike features of the figures were revolutionary. When revealed, it was like comparing the clarity of an 80s film to today’s 4K resolution. Da Vinci’s skill was unmatched.

Finally, the jagged rocks and fantastical background evoke a Lord of the Rings-like world. Why place them there? Like social media today, da Vinci’s goal was to captivate and hold your attention. And he succeeded.

Top Paris Tours

12. Venus de Milo

Artist Unknown | Island of Melos Greece | Marble | Sully Wing, Room 346

The Venus de Milo is arguably the most famous and sought-after statue in the Louvre. Translating to “Venus of Melos” (an island in Greece), the statue’s identity remains a mystery, largely due to her missing arms.

Without them, we lose the symbolic clues that often define ancient statues—like Mercury’s winged hat or Diana’s bow.

Venus, the Roman goddess of love, fertility, and sex, is a likely candidate due to the statue’s half-naked form and sensual curves. However, as the Greeks worshipped Aphrodite, the statue’s Roman name is technically incorrect.

Some speculate she could be Amphitrite, a Greek sea goddess revered on Melos, but her overtly sexual nature makes this less likely.

Regardless of her true identity, the Venus de Milo is celebrated as one of the greatest masterpieces of Greek or Roman antiquity. Its enduring fame is cemented by its appearance on the cover of Oxford’s Classical Art: From Greece to Rome. Need I say more?

11. St. Michael Overwhelming the Demon

Raphael | Oil on Wood Transferred to Canvas | Grande Galeriè Room 710, 12, and 16

Raphael was one of the most influential artists of the Renaissance. Had he lived longer than 37 years old, he would have accomplished much more. However, his impact was vast for his short time on Earth. Unlike Michelangelo and da Vinci who spent much of their time alone with a few key students, Raphael led armies of artists.

St. Micheal is an archangel and the right hand of God sent to protect humans. The image is one of the most powerful stories of the Bible in which Micheal defeats Satan and casts him into hell on behalf of God.

Nearby Raphael Works:

- Portrait of Doña Isabel de Requesens y Enriquez de Cardona-Angelesola

- Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (Returns to Louvre Feb 2021 – Room 711)

- La Belle Jardinière—The Virgin and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist

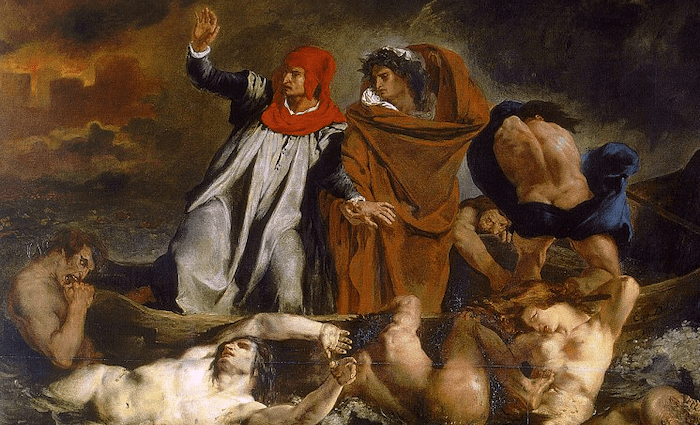

10. Dante and Virgil in Hell

Eugène Delacroix | Salon of 1822 | Oil on canvas

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) is often regarded as the most influential writer of the early Renaissance. His Divine Comedy, written in the nascent Italian language, revived literature after a 700-year drought since the fall of the Roman Empire.

It’s an epic poem divided into three parts—Heaven, Purgatory, and Hell—and Delacroix’s painting focuses on the most gripping of the three: Hell.

Why is Hell so universally feared? Because of Dante. His vivid descriptions shaped our collective imagination, and artists like Delacroix turned those words into haunting imagery.

Without The Divine Comedy and its artistic interpretations, our fear of Hell might not exist as it does today.

This was Delacroix’s first major painting, and it was immediately celebrated by proponents of the Romantic movement. The work is a passionate allegory, featuring Dante in his red cap alongside Virgil, the Roman poet who gave him history’s first guided tour—through Hell itself.

The influence of Michelangelo is unmistakable. Nearly 300 years after the Sistine Chapel, Delacroix drew inspiration from the master’s muscular, tortured figures. The condemned in this painting are hulking, half-dead forms strewn across the water, while demonic minions loom menacingly in the shadows.

Delacroix’s Dante and Virgil in Hell is a masterpiece of Romanticism, blending literary history, raw emotion, and the eternal fear of damnation into a single, unforgettable image.

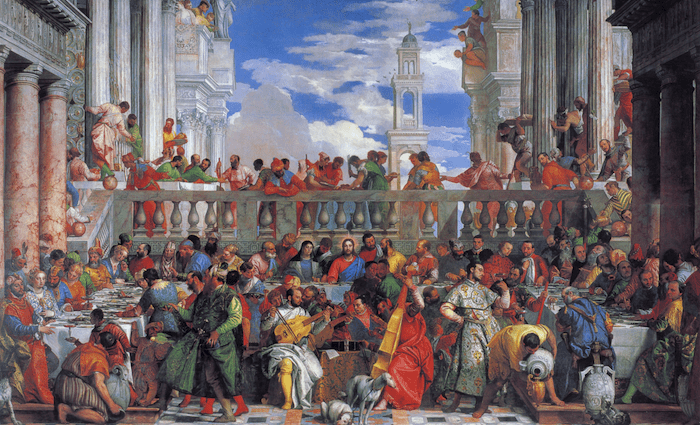

9. The Wedding Feast at Cana

Veronese | Oil on Canvas | 1563 | Dept of Paintings

The Wedding Feast at Cana is a painting of truly epic proportions, depicting the biblical scene where Jesus turns water into wine at Mary’s request.

In reality, the biblical event would have been far humbler, with beggars among the guests. But Veronese, true to his Venetian style, transforms it into a grand spectacle. His colorful, opulent approach—hallmarks of the Venetian school—elevates this work to masterpiece status.

The setting draws clear inspiration from Raphael’s School of Athens, while the seating arrangement nods to da Vinci’s Last Supper.

Like The Last Supper, the guest list is star-studded, featuring figures such as Francis I of France, Mary I of England, Vittoria Colonna, and Giulia Gonzaga. Veronese even includes himself, dressed as a musician in a white tunic.

This painting is not just a biblical scene; it’s a celebration of grandeur, artistry, and the Venetian flair for turning the ordinary into the extraordinary.

8. David with the Head of Goliath

Guido Reni | 1606 | Oil on Canvas | Grande Galarie

Guido Reni, a master of the late Renaissance and early Baroque, elevated canvas painting to new heights, and David with the Head of Goliath is proof of his brilliance. The epic tale of David, soon to be king, beheading the giant Goliath is a popular subject in art for good reason.

First, everyone wants to see themselves as David—the underdog who triumphs.

Second, it’s one of the most compelling stories in the Bible. While the New Testament leans toward peace, the Old Testament is rich with war and ambition, making it a favorite for artists and ambitious patrons alike.

This painting exemplifies Reni’s style. David is depicted with a youthful, almost angelic face and soft, flawless skin, a hallmark of Reni’s work. It’s a striking contrast to the brutality of the scene, making it all the more captivating.

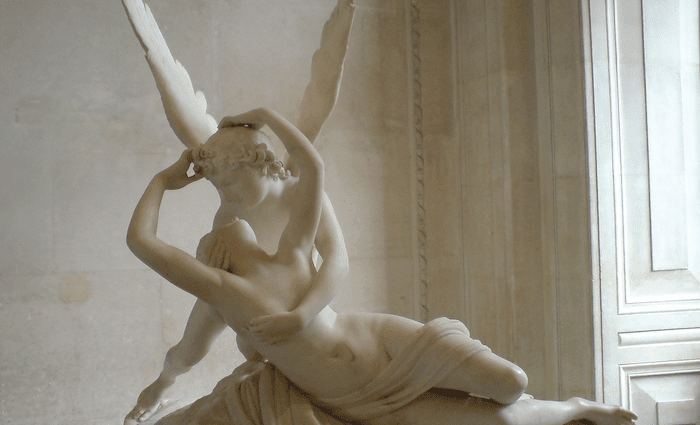

7. Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss

Antonio Canova | Carrara Marble | 1797 | Dept of Sculptures

In a breathtaking reinterpretation of an ancient legend, Antonio Canova captures the moment Cupid revives Psyche with a kiss of true love. The story begins with Venus, the goddess of love, tasking Psyche to retrieve a jar from the underworld, filled with the secret of divine beauty.

Despite Venus’s warning not to open it, curiosity got the better of Psyche. Instead of beauty, the jar contained the “Sleep of Innermost Darkness,” plunging her into a deep slumber.

Cupid, her true love, finds Psyche asleep with the jar beside her. Heartbroken, he takes her in his arms and kisses her, awakening her with the power of love. Canova’s sculpture immortalizes this tender moment, blending strength and vulnerability.

From the front, Cupid’s wings exude confidence and strength, while from the back, they convey urgency and fear. This multi-perspective approach, pioneered by Bernini during the Baroque period, is masterfully employed by Canova, making Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss a stunning testament to love, emotion, and artistic innovation.

Find Your Perfect Parisian Hotel

Maison Proust ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Le Marais • Terrace • Sauna

Luxurious hotel opened in 2023 with fabulous communal spaces and a Turkish spa.

Alba Opéra Hôtel ⭐⭐⭐

Opéra Arrondissement • Courtyard

Charcter-packed and quaint, legends like Louis Armstrong have stayed here.

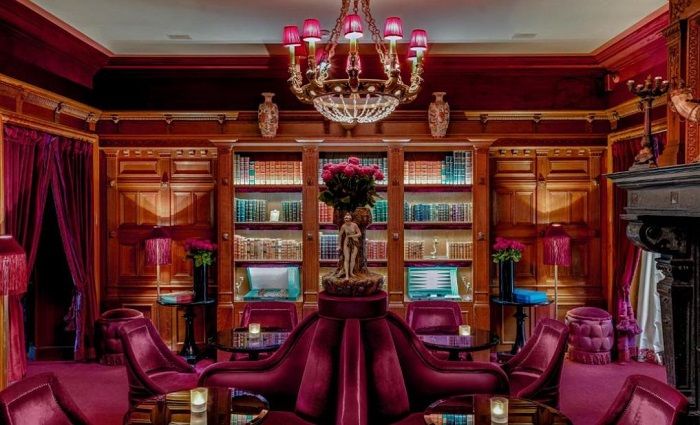

Maison Souquet ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Montmartre • Belle Époque Theme

Delightfully swanky and romantic, with an on-site lounge and spa.

6. Death of the Virgin

Caravaggio | Oil on Canvas | 1601-06 | Denon Wing, Room 710, 12, and 16

Why is Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin ranked so high? Because it’s a masterpiece that broke conventions—and was rejected for it.

Originally commissioned for Santa Maria della Scala in Rome, the painting was refused. Never heard of a commissioned painting being rejected? Then you need to dive deeper into Caravaggio’s tumultuous life–check out our podcast on Caravaggio.

The likely reason for its rejection? Vulgarity. Caravaggio’s raw, unidealized depiction of Mary’s death was too much for the church. He often paid beggars, prostitutes, and the impoverished to model for him, and his tragic, chaotic life is reflected in his art.

This painting strips away the fantasy of the Virgin’s final moments, replacing it with raw emotion. Mary’s bare feet, lifeless body, and the apostles’ somber expressions convey a stark realism. The apostles are full of doubt, their connection to Christ severed with Mary’s passing. Mary Magdalene sits beside her, head in hands, embodying grief and uncertainty.

Peter is likely at her side, though without his usual symbol—the keys to heaven—it’s hard to be certain. Still, his face conveys urgency and confidence, fitting for Christ’s chosen successor.

Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin is a brutally honest portrayal of loss, faith, and humanity, making it one of the most powerful works in the Louvre.

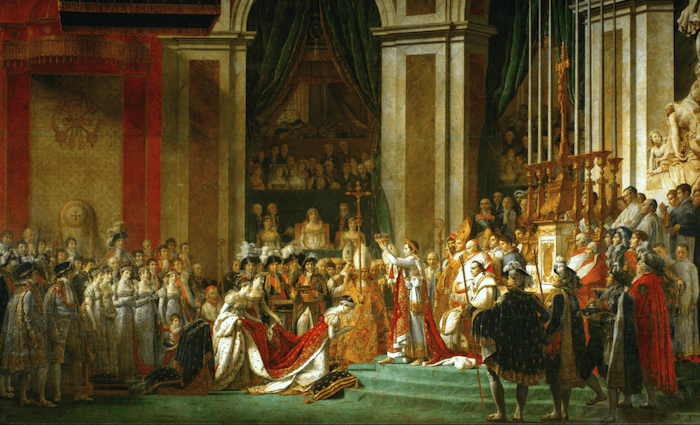

5. Coronation of Napoleon

Jacques-Louis David | Oil on Canvas | Dept of Paintings, Daru Room 702

Jacques-Louis David, the official painter of Emperor Napoleon, created this monumental masterpiece as his first commission for the emperor.

Ranking third on this list, The Coronation of Napoleon is not only one of the most important paintings in the Louvre but also one of the most significant works of art in the world.

At approximately 30 feet by 22 feet, the painting’s sheer size allows viewers to study the individual expressions of each figure.

David faced a unique challenge in capturing the larger-than-life persona of Napoleon, a man physically smaller than most but towering in ambition.

The event itself, held in Notre Dame Cathedral, was extraordinary. Pope Pius VII, present but clearly reluctant, is the only seated figure in the painting. His somber expression reflects his disdain for Napoleon, who had previously defeated papal troops, dragged the pope to France, and effectively humiliated the papacy.

Napoleon’s arrogance is on full display. In a bold break from tradition, he took the crown from Pius VII and crowned himself, then crowned his wife Josephine as empress. This act defied centuries of papal authority, where kings were invested by the pope—a symbol of divine approval. Napoleon’s self-coronation was a declaration of his supremacy, both as emperor and as a man who answered to no one, not even the Church.

David’s Coronation of Napoleon is a masterpiece of propaganda, power, and defiance, cementing its place as one of the most iconic works in the Louvre.

Most Important Figures

- Napoleon standing with the Roman victors, crown on his head and the crown of Charlemagne in his hands.

- Josephine kneeling in front of Napoleon with the empress’ crown on her head.

- Pope sitting behind Napoleon looking down with a grimace.

- Napoleon’s mother, sisters, and brothers in the loge playing a secondary role.

Nearby Works by David:

- The Intervention of the Sabine Women—The Sabine women were taken from the Sabine men from the Romans. The women then fell in love with the Romans. When their fathers and brothers came to avenge them, they came in between the lines stopping their kin from fighting their husbands. It’s one of the most epic Roman stories of all time.

- Leonidas at Thermopylae (300)

4. The Raft of Medusa

Théodore Géricault | Oil on Canvas | 1819 | Dept of Paintings, Mollien Room 700

The Raft of Medusa was an instant sensation, catapulting Théodore Géricault to fame.

The painting depicts the aftermath of a shipwreck, with a raft full of desperate survivors.

It serves as a scathing indictment of a French naval frigate that ignored their cries for help, leaving them to endure horrors like cannibalism and madness.

This masterpiece represents the pinnacle of French Romanticism, a movement that, like the Baroque, thrived on dramatic, emotionally charged scenes.

Géricault’s work is both a gripping narrative and a powerful critique, cementing its place as one of the most important paintings in the Louvre.

Nearby works by Géricault:

- Dante and Virgil in Hell

Top Day Trips From Paris

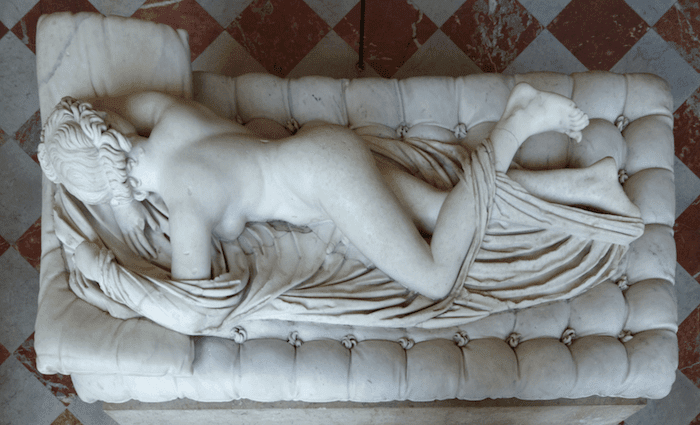

3. Sleeping Hermaphrodite on Bed

Unknown and Gian Lorenzo Bernini | p333

In classical antiquity, hermaphrodites—figures with both male and female attributes—were celebrated and sculpted with reverence, much like mythical creatures. This particular sculpture exemplifies the care and skill of ancient Mediterranean artists, who captured the human form with astonishing believability.

From behind, the figure appears to be a soft, inviting woman of perfect proportions. But upon closer inspection, there’s a surprise—an anatomical twist that challenges expectations. The craftsmanship is flawless, with the figure’s back and bottom appearing almost touchably soft, complemented by a robe that seems to defy the hardness of marble.

This particular hermaphrodite is of perfect composition in terms of believability other than the obvious syntax differences. If you walk up from behind you’ll see what appears to be a beautifully soft woman of practically perfect proportions inviting you into bed with her. Then all of a sudden, surprise, there are some extra parts.

Bernini’s Contribution

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the Baroque master rivaled only by Michelangelo, added the bed to this ancient second-century A.D. sculpture, likely a Roman copy of a Greek bronze original. The bed seamlessly enhances the composition, appearing as soft and inviting as the figure itself.

Sculpting the human form is one of the greatest challenges in art, as even the slightest imperfection is immediately noticeable. This piece not only achieves perfect proportions but also brings life to stone, making both the figure and the bed feel strikingly real. It’s a testament to the combined genius of ancient sculptors and Bernini’s unparalleled touch.

2. Winged Victory of Samothrace

Artist Unknown | 190 BC | The Daru Staircase in Dept of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiques p 438

In my opinion, the Winged Victory of Samothrace is the greatest sculpture in the Louvre—and one of the greatest in history. It stands alongside masterpieces like the Laocoön Group in the Vatican Museums and David in the Accademia.

Ancient Sculptors vs Renaissance, Baroque, and Beyond Sculptors

It’s important to note that the art of sculpting stone reached its pinnacle in ancient Roman times around the second century A.D. Yes, “our” era does include incredible sculptors like Michelangelo, Bernini, and Antonio Canova who are arguably the three best sculptors of stone in the last 500 or so years. That said, there would have been 100s who could have been their equal in Rome in the second century A.D.

You have to imagine that the Romans dominated Europe for a thousand years. When they were defeated in the fifth century by the Goths, they would have destroyed the city. What remains would be the scraps left over, yet the bottom of this list is dominated by ancient sculptures.

Ancient Sculptors vs. Renaissance and Beyond

While sculptors like Michelangelo, Bernini, and Canova are celebrated as the best of the last 500 years, ancient Roman and Greek sculptors had centuries of dominance. By the second century A.D., sculpting stone had reached its peak, with countless artists who could rival these later masters. The fall of Rome in the fifth century left us with only fragments of their greatness, yet ancient sculptures still dominate the conversation.

Why is it the Best Sculpture in the Louvre?

For me, the Winged Victory of Samothrace passes three critical tests:

1. Believable Anatomy

Even without arms or a head, the figure’s anatomy is flawless. The body is so lifelike that it feels real, a testament to the artist’s skill.

2. Emotional Impact

This sculpture was designed to intimidate enemies from the prow of a warship. Its presence exudes power, style, and culture, evoking awe and pride even today.

3. Unmatched Skill

The artist’s mastery is evident in the details. The figure’s body is both strong and sensual, with her stone clothing appearing impossibly transparent, revealing her belly button and breasts beneath. Her wings are a marvel of engineering, extending outward with no visible support—an incredible feat given the weight of marble.

What’s even more astonishing is that this masterpiece was created for the prow of a ship, combining artistry with functionality. The risks taken in crafting her wings and the precision required to balance the sculpture make it a triumph of ancient skill, unmatched for over a thousand years.

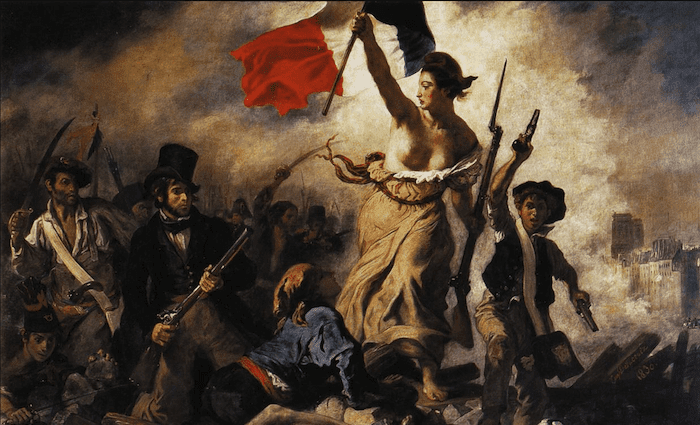

1. Liberty Leading the People

Eugène Delacroix | Salon of 1831 | Oil on Canvas

Eugène Delacroix, the Michelangelo of French Romanticism, earns the top spot on this list with Liberty Leading the People.

This masterpiece is an allegory of the 1830 revolution, a defining moment in French history.

Liberty, the bare-bosomed centerpiece, holds the Tricolore flag—the same flag carried by the militia during the storming of the Bastille and still used today.

The figure of Liberty is iconic, rooted in ancient Greek imagery. Her semi-nude form echoes classical references, much like the Winged Victory of Samothrace. She also stands as a symbol of freedom in New York Harbor, connecting her to a universal ideal.

The figures surrounding Liberty represent unity across classes: a top-hatted member of the upper class, a factory worker, a student, and others stand side by side. Delacroix’s ability to create lifelike, emotionally charged figures draws viewers into the passion and reality of the scene.

This painting is the greatest in the Louvre because it captures the spirit of revolution, the power of unity, and the timeless pursuit of liberty. It’s a story that’s as real and moving today as it was in 1830.

What makes Liberty Leading the People even more fascinating—and ironic—is that Delacroix was working for King Charles X, the very monarch whose oppressive policies sparked the July Revolution.

The man who painted the most iconic image of rebellion was, in essence, a hypocrite and a sell-out. And that’s my favorite part. It’s a reminder that even the greatest works of art can come from deeply flawed, conflicted individuals.

Delacroix’s masterpiece isn’t just about liberty—it’s also about the contradictions of human nature. The painting was recently restored brighter than ever which is why you need to see it in person!

Louvre Tours

Did you enjoy the stories behind these incredible works of art? This blog is not meant to replace a guided tour but instead to make it better. Experience our tours of the Louvre, led by the most passionate guides in Paris. They’ll undoubtedly elevate your experience.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if a Louvre Museums tour is worth it.

Where To Stay in Paris

With a city as magnificent as Paris, it can be hard to find the perfect hotel at the perfect price. Explore the best hotels and places to stay in these incredible neighborhoods in Paris.

Great discussion of the masterpieces in the Louvre! Thank you.

Thank you for saying Liberty Leading the People is the most important work in the Louvre painting collection. I have been to the Louvre 3 times, and it captures me each time. More magnificent than old Mona Lisa, it captures your heart with possibilities. Beautiful painting

Obviously, a lot of personal preference goes into it, but I believe it has far more depth than the Mona Lisa on a “storytelling” level and is more captivating.