Planning to visit the MET in New York City but unsure what famous artwork you should see? Don’t worry, we’re MET experts so we have you covered. Here are the most famous sculptures that you absolutely must see when visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Pro Tip: Visiting the MET in NYC? It’s easier to organize your trip when you have all your resources in one place. Bookmark this post along with our New York City Guide for more planning resources, our best MET and NYC tours for a memorable trip, and the top things to do in NYC.

The 13 Must-See Sculptures At The MET

Art is about emotion. It’s the result of an artist unleashing their innermost thoughts and feelings onto a piece for all to witness. It’s such a powerful act that many have been criticized, scrutinized, and even killed just for doing it.

If you look at the sculpture and don’t feel anything, it’s only because you haven’t heard its story. This is the very reason we recommend guided tours. The purpose of art is to inspire emotion and you don’t have to have a strong art background to appreciate it. It definitely helps, but it’s not essential.

That’s why we have tour guides with a strong art background skilled in the art of storytelling—so anyone can appreciate celebrated works of art in world-class museums no matter their background. That’s what we do and the MET is the perfect place to join a tour!

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if a tour of the Met is worth it.

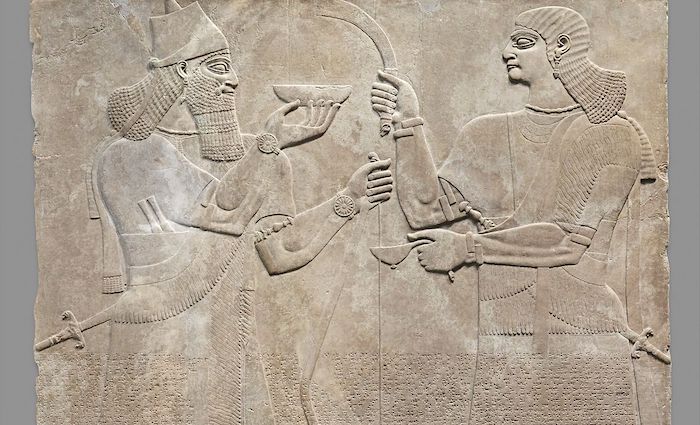

13. Relief Panel

Unknown | 883–859 B.C. | Gypsum Alabaster | Gallery 401

Picture something you’ve created with your hands. Now imagine that object lasting for three millennia. How could I not add it to this list? I also think the subject matter of this relief is pretty cool. While this art piece is not a three-dimensional sculpture, it still has the ability to fascinate.

It originally resided in the palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II. In the relief, there are two men. The left one is probably Ashurnasirpal and on the right is a servant. It is a credit to the artist (and the dry climate) that after almost 3,000 years we can make out the entire relief in complete clarity.

For example, you definitely didn’t want to mess with the king. On his body, he carries a sword, two daggers, and a bow. He obviously had some security issues. To lighten things up he’s also holding a bowl with wine in it (why drink from a cup when you can drink from a bowl?)

The beardless man on the right was probably a eunuch. He also has a sword, but in his right hand, he’s holding a fly swatter to protect the king against flies. Since this is a tomb relief, imagine how serious a problem flies were if had this pictured on your grave. Below that you can see script, which cuts right across the art piece. This inscription tells of the king’s accomplishments during his lifetime.

A distinctive feature of the Northwest Palace is the so-called Standard Inscription that ran across the middle of every relief, often cutting across the imagery. It is thought to have had a magical function, contributing to the divine protection of the king and the palace.

MET Official Archives

12. Head of a Queen Mother

Unknown | 1750–1800 | Brass | Gallery 352

Head of a Queen Mother is definitely different than most of the other sculptures on this list. It’s a rendering of an iyoba or mother of the oba (king) that explains the importance of women in the Benin kingdom’s political hierarchy.

This art piece hails from the kingdom of Benin, which would be in today’s southern Nigeria. The 15th century is the first time this title appears when Idia, mother of king Esigie, used her political skill to save a dissolving kingdom.

From that time in history, the queen mother exerted considerable force in the kingdom. The iyobas enjoyed a separate palace, female servants, and of course the right to have a brass sculpture made of themselves. I commend the MET for bringing in diverse artworks such as these, so we can learn about kingdoms and areas that otherwise we probably never would.

11. Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water Moon Form (Shuiyue Guanyin)

Unknown | 11th Century | Wood | Gallery 208

The title of this work is a mouthful. Let’s start with some definitions of the words to make this sculpture a bit more user-friendly. Bodhisattva is “one whose goal is awakening,” in Buddhism—hence, an individual on the path to becoming a buddha. Avalokiteshvara means “Lord who looks down with compassion.”

Now that we understand this is a statue of an enlightened individual who has god-like qualities full of compassion, we can enjoy the statue better! He sits here with his right knee raised and his left leg crossed in front of his body. This particular stance shows the Water Moon manifestation and therefore depicts the divinity in his Pure Land or personal paradise.

While this mythical paradise was thought to be on an island in Southern India, the 15th-century followers identified it with Mount Putuo, which is an island on the east coast of Zhejiang. At that point, it had become an important pilgrimage site.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our guide to the Met.

10. The Intoxication of Wine

Clodion (Claude Michel) | 1780–90 | Terracotta | Gallery 552

Clodion was a French sculptor whose career spanned the last moments of the old regime and into Napoleon’s reign. His specialty was Bacchic orgies, as you can see above. As with most artists of the time, he went to study art in Rome and caught the “Classic” bug.

The Intoxication of Wine is Rococo, which was his style of choice and I have to say he nails it perfectly. While the neoclassical style was emerging during this time, the movements in the above sculpture show a beautiful fluidity. In his later works, he also made statues in the neoclassical style.

I have found that there are two main themes in expressing true emotion in sculpture: pain and joy. A great example of pain is the Ugolino statue (see below) while joy is perfectly expressed here. While most of us (I assume) have not taken part in Bacchic orgies, we can all appreciate the warm happiness that spreads over our bodies with some wine. The look on both their faces leaves us with no doubt about their feelings.

The seeming spontaneity of this composition, a rapturous embrace, in which it appears that the senses are totally abandoned, was achieved only after much meditation. This work is one of the most minutely studied of all the Bacchic orgies that were Clodion’s specialty. The front and back show deliberate adjustments of angles, openings, and masses, all checked and balanced as the model passed under his fingers on his trestle table.

MET Official Archives

9. Bronze Statue of Eros Sleeping

Unknown | 3rd–2nd Century B.C. | Bronze | Gallery 164

It is always super exciting to see a bronze statue from antiquity. The Romans melted down bronze statues for their metal. As aghast as you might be at that thought, don’t worry—they usually made a copy in marble first. So many copies exist of this statue in marble that this could be the original.

Bronze Statue of Eros Sleeping is from the Hellenistic period. This is the period of the death of Alexander the Great (323 B.C.) and the beginning of the Roman Empire (31 B.C.). During this time, Greek culture flooded the world from Rome all the way to Afghanistan and India.

According to the Met Official Archives, ” The Hellenistic period introduced the accurate characterization of age. Young children enjoyed great favor, whether in mythological form, as baby Herakles or Eros, or in genre scenes, playing with each other or with pets”.

For example, Eros, the god of love is depicted here without his cruel arrow. In Archaic poetry, he was known as often being cruel. Looking at this statue, there’s only innocence. In today’s world, you get professional photos taken of your children. Back in the day, you would have an artist use their face to adorn a statue and immortalize them.

8. Bacchanal: A Faun Teased by Children

Gian Lorenzo Bernini | 1616–17 | Marble | Gallery 534

Gian Lorenzo Bernini was like King Midas—almost anything he touched turned to gold. He was by far the most prolific and famous sculptor in the Italian baroque period. Bernini was only 18 years old when he created this, so it contrasts with his later more refined works.

Needless to say, creating something of this caliber when you’re 18 years old is quite impressive. You can already see his attention to minute detail and the expressiveness of the figures. This is a foreshadowing of his Santa Teresa or Apollo and Daphne, which are in Rome.

Bacchanal: A Faun Teased by Children is a playful statue where a faun appears to be at the mercy of two small children. A faun is a mythical forest creature, so it’s a bit ironic that human children would be playing with it. Starting back in the Hellenic age, adding children to artwork became quite popular and had a resurgence during the baroque period.

The influence of his father, the Florentine-born Pietro, can be seen here in the buoyant forms and cottony texture of the Bacchanal. The liveliness and strongly accented diagonals, however, are the distinctive contribution of the young Gian Lorenzo.

MET Official Archives

7 .Burghers of Calais

Auguste Rodin | Modeled 1884–95, Cast 1985 | Bronze | Gallery 548

Auguste Rodin remains arguably the most famous French sculpture to date. He is most famous for his sculpture The Thinker, which is located at the Rodin Museum in Paris, France.

I personally find the story behind the Burghers of Calais fascinating! English king Edward III (1312–1377), besieged the French town of Calais. Once the city surrendered, the king ordered the six most prominent citizens (burghers) to come to him. They also had to bring the keys of the city, with feet bare and ropes around their neck. The rope signified that the king ordered them to be beheaded!

Imagine the feeling of dread knowing that you’re walking to certain death! However, not all is bleak. Unbeknownst to the burghers, the English Queen Philippa intervenes on their behalf to release them.

Rodin’s masterpiece displays the difficult arrangement of the figures. Some are looking straight ahead, while others are looking to the side. Some are in motion while others are standing still. This variety in one sculptural group expresses his mastery of various movements that he cast in bronze.

Not ready to book a tour? Read why a guided Met tour is worth it.

6. Perseus with the Head of Medusa

Antonio Canova | 1804–6 | Marble | Gallery 548

The Countess Valeria Tarnowska of Poland purchased this replica of Perseus. The original Perseus that Canova made is in the Vatican Musuems. Canova took his inspiration for this piece from Greek mythology.

Perseus was the slayer of the Gorgon Medusa and rescued Andromeda from the sea monster. He was a demi-god and the son of Zeus and Danaë. A wily king tricked Perseus to obtain the head of Medusa.

Since her gaze turned anyone to stone, he guided himself to her by the reflection in his shield. He then beheaded her while she slept. Canova chose this victorious moment for his art piece. Like most artists before him, Canova would have been extremely influenced by classical artists.

Today, artists can freely visit a museum, but back in the 18th century, the best place to visit was the Vatican Museums. A perfect example of influence for this statue is the Apollo Belvedere from the Vatican. The refined, noble face is almost a direct copy from the Apollo.

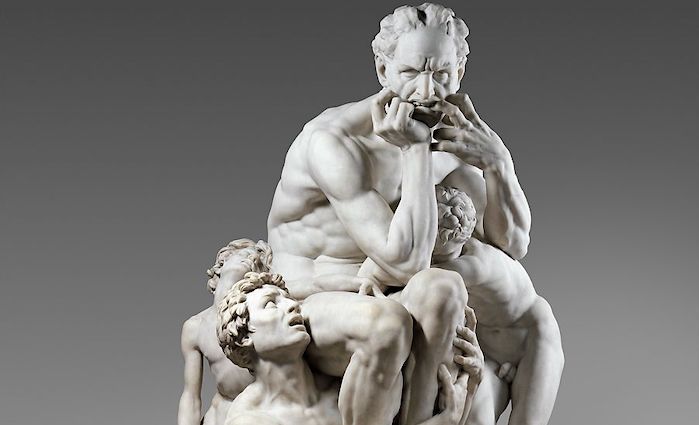

5. Ugolino and his Sons

Jean Baptiste Carpeaux | 1865–67 | Saint-Béat Marble | Gallery 548

Personally, I feel that few statues can express true pain and fear. Ugolino and his sons capture this in a way that is similar only to the Laocoön Group. Read below to understand the story behind this.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, “Jean Baptiste Carpeaux’s works contain a lively realism, rhythm, and variety that were in opposition to contemporary French academic sculpture, and form a prelude to the art of Auguste Rodin, who revered him.”

The theme for Ugolino and his sons goes back to the 13th-century work by Dante, “The Divine Comedy”. Officials ordered the Pisan count Ugolino Della Gherardesca, his sons, and his grandsons to prison for treason. They died of starvation in prison. In the XXXIII canto of Inferno, Dante mentions this horrible story.

Carpeaux studied art in Rome. In this piece, you witness the influence of previous masters on him. You can see from the abundant muscles and minute detail that Carpeaux was an avid follower of Michelangelo. This is especially true concerning Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.

“The grip of all of these people, the density of this composition, communicates the crisis.”

Sam Pinkleton, Theater director

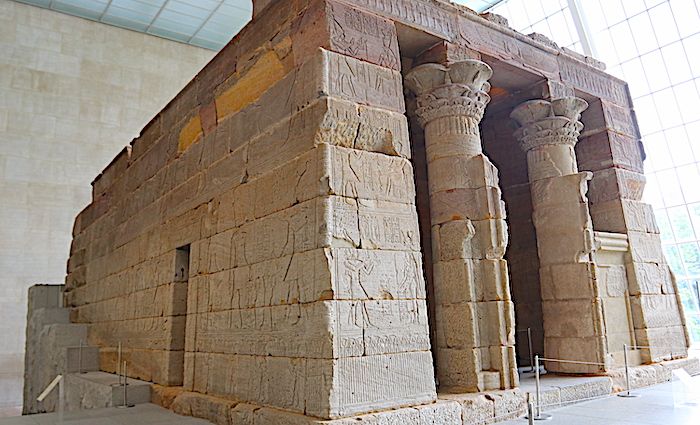

4. The Temple of Dendur

Unknown | 10 B.C. | Aeolian Sandstone | Gallery 131

I have to give huge props to the museum curator who organized the installation of the Temple of Dendur at the MET. Usually, to witness a life-size temple you would have to go on-site, in this case to Egypt.

However, the MET has brought Egypt to New York City! They set it up so that you only see the temple after making a sharp left turn. At that point, a gigantic temple opens up in front of you.

In the 1960s, the Egyptian government wanted to control the flooding of the Nile river. So, they built the Aswan Dam. However, a dam creates a lake that would have covered archeological sites, including Dendur where this temple comes from.

Many countries came together to help Egypt with supplies, equipment, and funds to map out the ancient territories in this area. To show their appreciation to the United States for their help, the Egyptian government gave this temple and gateway as a gift.

Once you’re in the gallery, you’ll be astonished by the size of the gateway and temple itself. The year of its construction is 15 B.C., which means that it was built during the Roman occupation. The little temple itself is dedicated to the goddess Isis together with Pedesi and Pihor, deified sons of a local Nubian ruler.

If you’re a Roman History nerd, then you’ll be pleased to know that Emperor Augustus is also mentioned in this temple. The depiction of the Pharaoh is none other than Augustus, the first emperor of Rome!

3. Dancing Celestial Deity (Devata)

Unknown | Mid 11th Century | Sandstone | Gallery 241

The Dancing Celestial Deity would make Gumby proud. The body twists and distorts in a way that is definitely not human, which is the point. I’ll explain.

The Dancing Celestial Deity or Devata is performing a dance in honor of the gods. This life-size sculpture would have been placed inside a Hindu temple. Since a Hindu temple is the heavenly home of a presiding deity, the Devata is there to honor the god.

Why are the dancer’s legs going to the right while the torso and head are turning to the left? The sculptor would have contorted the dancer’s face and body according to prescribed canons of beauty. This is similar to Renaissance Christian art where a woman would be depicted with blond hair and very voluptuous.

According to the MET’s official archives, “The extreme flexion reflects dance positions (karunas and sthanas) described in the Natyasastra, an ancient dramatic arts treatise. It is understood in Indian aesthetics that such positions enhance the appreciation of beauty.”

2. Winter

Jean Antoine Houdon | 1787 | Bronze | Gallery 199

What feeling is worse than the biting cold? The humid cold goes right to your bones, no matter how many layers you have on. As I mentioned earlier, the two main expressions in sculpture are joy and pain. The pain this woman is feeling from the cold is palpable. Just looking at it makes me shiver now. The skill involved in bringing alive such emotion from a piece of cold metal never ceases to amaze me.

Surprisingly, Jean Antoine Houdon was primarily known for his portraiture. I say surprisingly because this statue is not a portrait and is fascinating to look at. Houdon grew up in Versailles the son of a servant. His father then served as a concierge for École des Élèves Protégés where recipients of the Prix de Rome were schooled. In this way, Houdon grew up surrounded by these budding artists and eventually received the prize himself in 1761.

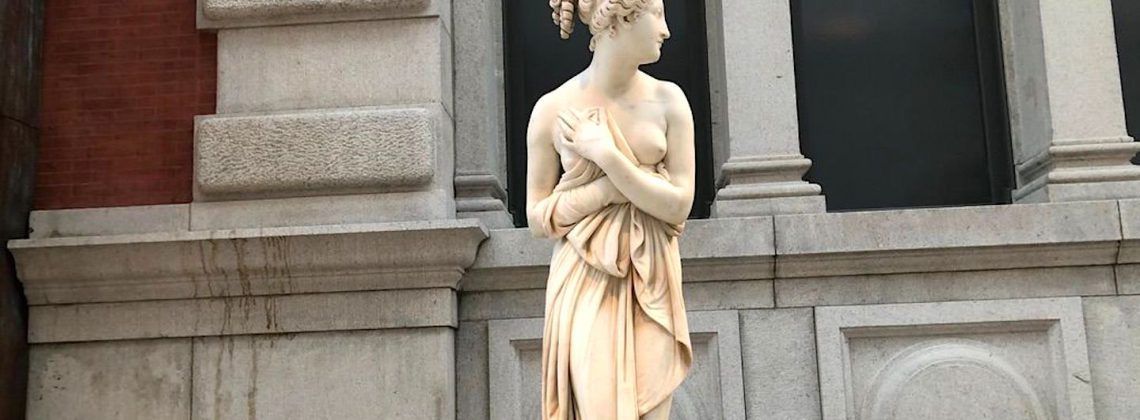

1. Venus Italica

Workshop of Antonio Canova | ca. 1822–23 | Variant of Marble First Executed 1810 | Carrara Marble | Gallery 515

When I think of Antonio Canova, I envision a huge torch of greatness being passed down to him from his predecessors. In my head it is Donatello (15th century), passing it to Michelangelo (16th century), passing it to Bernini (17th century), passing it to him.

Don’t be put off by the fact that this statue was done by his workshop. Successful artists had so many commissions it was impossible to do them all. The master would usually create the drawing, define how it should be carved, and then the workshop took over. Similar to Steve Jobs creating the idea of the iPod and engineers making it happen.

This Venus Italica is actually the third Venus that Canova created. The first Venus is in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence. In 1804, Ludovico I, King of Etruria, ordered the second Venus as a replacement for the original Medici Venus taken by the French. The third Marquess of Londonderry purchased this replica in late 1826 or early 1827 where it remained until 1962.

Antonio Canova is considered the greatest Neoclassical sculptor of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Along with the painter Jacques Louis David, he was credited with ushering in a new aesthetic of clear, regularized form and calm repose inspired by classical antiquities.

Christina Ferando, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Not ready to book a tour? Find out more about how to visit the Met museum.

Where To Stay in NYC

New York City is the center of the universe to those who adore this iconic city. Choose the best neighborhood to stay in as you plan your upcoming trip to the Big Apple.