For many, Florence is synonymous with the Renaissance. Indeed, the city boasts a bevy of artistic and architectural wonders from that time period. However, Florence’s history doesn’t begin and end with the likes of Michelangelo, Machiavelli, or the Medici. Learn more about Florence’s history below!

Pro Tip: Planning your trip to Florence? Bookmark this post in your browser so you can easily find it when you need it. Check out our guide to Florence for more planning resources, our best Florence tours for a memorable trip, and how to see Florence in a day (with itinerary).

A Short History of Italy’s Renaissance City: From Roman Times to the Present

Scholar Robert Clark believes there is both Florence and Firenze to consider. Firenze (Italian for Florence) is where today’s residents of the Tuscan capital live and work. Florence, on the other hand, “is the place where the rest of us come to look.”

Indeed, we travelers have eyed Florence for centuries. As historian Eric Cochrane explains, Florence became a vital stop on the Grand Tour’s itinerary by the late 17th and early 18th centuries. What fascinated those northern European and American visitors about Florence still draws millions of tourists each year. And what is so appealing?

It’s the city’s incredible collection of art and architecture, dating primarily to the days of the Renaissance. It’s easy to tell as soon as you catch a glimpse of the Duomo that Florence is a city full of architectural and artistic treasures.

Furthermore, many Italian natives produced such works of art, architecture, and literature, garnering international fame for themselves and Florence. Even today, scholars continue to marvel at how this one place gave the world legendary names like Michelangelo, Donatello, Leonardo, and Dante Alighieri to name just a few.

But Florence’s story is not confined to famous Renaissance works of art, architecture, and literature. It is a city that once stood as one of the most powerful and wealthiest city-states of Italy. And one of Europe’s most intriguing dynasties, the Medici, dominated Florence for several centuries.

Finally, Florence played a major role in shaping the political and cultural landscape of modern Italy. So, let’s explore Florence’s history!

c. 59 B.C. – A.D. 500

Foundation | Roman Settlement | Flourishing Town

Scholars continue to debate Florence’s earliest origins. We know the Etruscans settled in the vicinity of present-day Florence at Fiesole in the 7th century B.C. However, historian Larry A. Silver explains that we just don’t know for sure if there was a pre-Roman settlement within the boundaries of today’s city.

From historian Bard Thompson, we learn that Florence began as a Roman military colony called Florentia in 59 B.C. It’s believed that Florentia owed its foundation to none other than Gaius Julius Caesar. Regardless, Florentia certainly existed during the prime of Caesar’s political career in Rome.

Rather quickly, Florentia acquired the trappings of a significant Roman city. For example, scholar Christopher Hibbert says you would have seen several impressive temples and other public buildings. At the same time, Thompson tells us that trade facilitated by the Arno river made Florentia an important commercial center.

According to Larry A. Silver, Florentia means “Flourishing Town” and by the 3rd century A.D., the place we call Florence certainly flourished. In fact, Hibbert notes that in that time period, Florentia served as a provincial capital of the Roman Empire.

A.D. 500 – A.D. 1115

Roman Breakdown | Foreign Conquerors | Political Change

Eventually, Florentia fell victim to the same pressures faced by the rest of the Italian peninsula as the Western Roman Empire collapsed. Foreign raiders beginning with the Goths wreaked havoc on Florentia and other parts of Tuscany. For instance, scholar Tim Jepson mentions the city’s conquest by Gothic king Totila in A.D. 552. Jepson says that this proved so devastating that within two decades, the Lombards seized Florence.

Lombard rule came in the form of dukes residing in Pavia and later Lucca. However, Jepson tells us that Charlemagne’s Franks conquered much of Italy by the late 8th century. As a result, the Franks installed imperial margraves to rule over Florence from Lucca. These margraves, according to historian John Najemy, became key players in the Holy Roman Empire.

They also helped the spread of Christianity through Florence and Tuscany. Jepson notes that the widow of Margrave Uberto founded Florence’s Badia in 978, the first monastic foundation in the center.

Political change shook Florence in 1115. According to historian Roger Crum, that year marks the beginning of Florence’s era of popular government. So, what caused this change? Well, Najemy explains the immediate cause as the death of Matilda, which marked the end of the imperial margravate from Lucca.

A.D. 1115 – A.D. 1300

Power to the People? | Bitter Disputes | Duomo

While she still ruled from Lucca, Matilda favored Florence. As a result, in the year of her death in 1115, Matilda granted Florence the status of independent city-state (comune). By 1125, Florence became governed by a council of 100 men. Najemy notes that these men belonged to the emerging merchant class.

Political change reflected Florence’s booming economic conditions. For example, Hibbert says that while the city became associated with banking, it first witnessed a boom in textiles. Indeed, Jepson says by the 1150s, Florence’s booming textile business helped the population expand to make the city one of the largest in Europe.

Good times, however, ultimately yielded to a prolonged split in Florence. The root of this crisis stemmed from disputes within the Holy Roman Empire and later the papacy. As a result, in the 13th century and beyond, Florence and much of Italy became a battleground between the Ghibelline and Guelph factions. Although definitions changed over time, historian Norman Davies explains that Guelphs were pro-papacy. Ghibellines, on the other hand, backed the emperor. Historian Simon Jenkins believes this split inspired Shakespeare’s Montagues and Capulets!

However, not all events in this time became bound up in this split. In fact, we’ll pause here to talk about the Duomo. You could say Florence’s magnificent Duomo is a product of what we would call keeping up with the Joneses. For instance, historian Philip Parker explains that the construction of impressive cathedrals at Pisa and Siena by the 1290s galvanized Florentine leaders into action. Not to be outdone, the resulting cathedral eventually became the fourth largest church in Europe. But the cathedral was far from completed as we say goodbye to the 13th century here.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our article on the best Florence tours to take and why.

A.D. 1300 – A.D. 1406

Expansion | Banking | Rivalries and Revolts

Florence continued to grow in wealth and influence in the 14th century. In fact, by the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Florence emerged as a major banking center in Europe. For example, the historian Simon Jenkins explains that Florentine silver coins, called florins, became a much-desired currency.

Though banking and textiles made Florence a wealthy city, not all ran smoothly in the 14th century. Hibbert describes the 1340s as a challenging decade for Florence. He also mentions an economic crisis stemming from the bankruptcy of several Florentine banks. Moreover, the Black Death plague dramatically reduced the city’s population.

Further strife resulted from growing inequities between laborers and wealthy bankers, merchants, and other propertied groups. Ultimately, the high point of this labor unrest came in 1378. According to historian Roger Crum, Florence witnessed the so-called revolt of the Ciompi that same year. As historian Paul Strathern explains, this revolt is significant in large part because it introduces us to a major family we will meet in the next section: the Medici.

Wealth brought power and power meant expansion. In fact, rivalries with neighboring city-states like Pisa produced a conflict that a confident Florence won in 1406. As a result, Hibbert explains that Florence conquered Pisa and thus secured an outlet to the sea.

A.D. 1406 – A.D. 1478

Medici Rule | Splendor | Lorenzo’s Magnificent

The Medici family began its ascent to the levers of power in the late 1300s. Strathern states that Giovanni Bicci de’ Medici amassed the family’s wealth via banking. And Jepson tells us that the Medici initially supported some of the aggrieved lesser guilds that were on the frontlines of the labor unrest discussed above. Furthermore, Hibbert says that Florentine authorities imprisoned Giovanni’s son, Cosimo, for his political leanings in 1431.

Two years later in 1433, Florence’s rulers embroiled the city in an unpopular war with Lucca. As a result, these rulers forced Cosimo into exile. However, scholar Fabrizio Ricciardelli explains that Cosimo’s exile proved brief. In fact, within a year he was not only back in Florence, but the most powerful man in the city. Cosimo il Vecchio (as he became known) essentially dominated Florentine politics for the next three decades, according to Strathern.

As the Medici family began consolidating its grip on Florence, one Renaissance master completed the Duomo’s cupola. After 16 years of construction, architect Filippo Brunelleschi witnessed the final touches on what became the largest masonry dome in the world in 1436. Scholar Philip Parker explains that, in many ways, Brunelleschi’s work is a quintessential example of Renaissance architecture.

We now reach the zenith of Medici power and cultural patronage during the reign of Lorenzo the Magnificent (1469-1492). Indeed, Lorenzo’s court bustled with intellectual and artistic creativity. The arts certainly flourished under Medici rule. For instance, art historian Ian Chilvers says young Leonardo da Vinci worked in Florence until the early 1480s when he moved to Milan. Furthermore, by 1470 Sandro Botticelli emerged as one of the leading artists thanks to Medici patronage.

Ready to come to Florence now? Discover how to see Florence in just 48 hours, our favorite things to do here, plus where to stay around the city.

A.D. 1478 – A.D. 1512

Conspiracy | Invasion | “Mad Monk”

Lorenzo and the Medici faced threats on multiple fronts by the late 1470s. In fact, as historian John Najemy explains, Lorenzo survived an assassination attempt during the Pazzi Conspiracy in 1478.

Conflict dominated Italy by the close of the 15th century in the so-called Italian Wars. According to historian Jeremy Black, Italy became the battleground of Europe. Moreover, Italy increasingly came under the control of France or Spain. Jepson states that the French under King Charles VIII came for Florence in 1494. This led to the flight of Lorenzo’s successor Piero.

In Florence, all the violence and conflict produced a radical leader named Girolamo Savonarola. A Dominican monk who led the San Marco Convent, Savonarola gained fame in the early 1490s for his fiery sermons. As scholar Christopher Hibbert says, though Savonarola railed against the city’s “decadence,” he reserved much of his anger for the Medici. Although conflict and crisis pushed the Medici out and led to a republican government, Savonarola controlled Florence.

Savonarola only briefly ruled though as his austere policies drew resentment. Scholar Christopher Hibbert says Savonarola made a powerful enemy in Pope Alexander VI. As a result, Savonarola was burned at the stake in 1498. Shortly after Savonarola’s execution, Florence resumed its place as a benefactor of magnificent art. Strathern says that’s when the city’s republican government sponsored Michelangelo’s iconic David in 1501.

A.D. 1512 – A.D. 1569

Medici Strike Back | Machiavelli | Grand Dukedom

Aided by papal and Spanish troops, the Medici returned to power in 1512. However, the Medici did not just return to power in the person of Giuliano, Duke of Nemours—they came to settle scores. Successive Medici rulers essentially became proxies for the authority of Pope Leo X (himself a Medici), according to historian Eric Cochrane. Furthermore, Jepson says that when Giulio de’ Medici became Pope Clement VII, he essentially remained the absentee ruler of Florence.

Such political changes occurred against the backdrop of the continuing Italian Wars. Once again, the Medici were driven from Florence in 1527 as republicans fought back. However, Black notes that Holy Roman Emperor Charles V seized Florence in 1530 and installed Alessandro de’ Medici in power.

Alessandro became the first Medici to bear the title Duke of Florence, as noted by Jepson. With Holy Roman imperial and papal approval, another Medici, Cosimo, became Cosimo I Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1569.

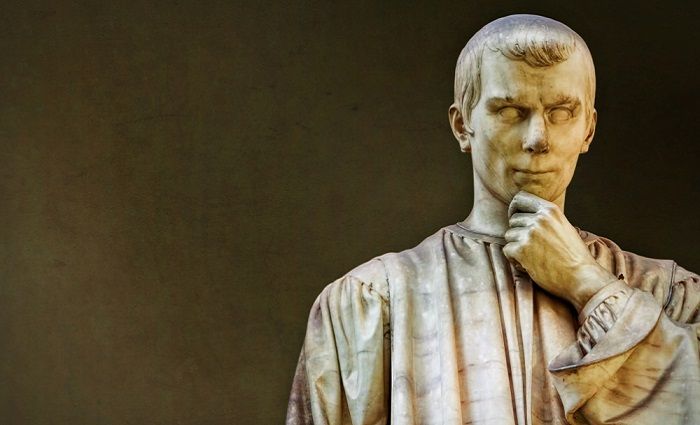

All this instability also produced one of the world’s most famous philosophers and observers of political power. That would be Niccolò Machiavelli. Historian Simon Jenkins says that Machiavelli believed that only through security could a moral prince gain influence over the conduct of affairs. Informed by the chaos of his era, Machiavelli’s treatise “The Prince” became required reading for any would-be leader.

A.D. 1569 – A.D. 1800

Decline | Foreign Rule | French Revolution

Despite the fancy title, the grand dukedom marked the beginning of the end for the Medici. However, not all of this story is about Medici decline. In fact, since the late 16th century, the Medici displayed art treasures at the Uffizi Gallery. As a result, art historian Ian Chilvers explains this makes the Uffizi one of the oldest art galleries in the world. By the mid-18th century, the collection at the Uffizi became the property of Florence, on the condition that the art would never leave the city.

Eventually, though, the Medici were permanently displaced as Florentine rulers. As historian Eric Cochrane explains, this came in 1738 when the grand dukedom transferred to Habsburg relatives from the House of Lorraine. Moreover, Cochrane tells us the first Lorraine duke was Francis Stephen, the future Emperor Francis I of Austria.

French revolutionaries eyed the various Italian states as prime destinations to export their ideas and defeat enemies like the Austrians. As a result, historian Michael Broers explains that the Tuscan grand dukedom’s days were numbered. Like dominoes, various Italian rulers fled their territories before the advancing French revolutionary army. The French would soon come for Tuscany’s rulers.

A.D. 1800 – A.D. 1870

Napoleon and Nationalism | Unification | Italy’s Capital

As in virtually any history of a European destination, when we reach the 19th century we must talk about Napoleon. Indeed, historian Alexander Grab explains Napoleonic French rule brought sweeping changes to Florence and much of Italy.

Across Italy, Napoleonic rule also contributed to a growing wave of Italian nationalism. In fact, over the course of the first half of the 19th century, historian David Gilmour says many began to see themselves as not just Florentines or Tuscans, Romans, or Milanese, but as Italians. The nation was finally unifying. However, as one nationalist leader and one-time prime minister of Sardinia Massimo D’Azeglio put it, the task before Italian leaders upon unification in 1860 was to “make Italians.”

Part of that process involved creating a modern Italian state. In 1865, Italian royals and government officials relocated the national capital from Turin to Florence. The royal family took up residence at the Pitti Palace. However, Florence’s tenure as Italy’s capital city would be brief. As historian Chris Duggan explains, Italian forces conquered Rome in September 1870. Shortly thereafter, officials migrated to Rome and made the city Italy’s new capital.

Although Florence lost out on remaining Italy’s capital city, its culture left a lasting impression on the young country. Perhaps its most enduring cultural legacy is that much of the Tuscan dialect became the standardized form of Italian. In fact, as historian Spencer M. Di Scala explains, this linguistic shift began in the midst of the Italian unification movement in the mid-19th century.

A.D. 1870 – Present

Tourism Boom | Disasters | Legacies

Much of Florence’s historic center became a tourist showpiece by the early 20th century. In fact, as historian D. Medina Lasansky tells us, Florence and many surrounding Tuscan hill towns became beneficiaries of preservation projects under Mussolini’s fascist dictatorship. Moreover, in addition to tourists, the city attracted its share of expats, particularly literary and artistic figures.

For as devastating as the experience of war and occupation was for Florentines, yet another disaster struck in the postwar years. The lifeblood of the city, the Arno river, flooded Florence on November 4, 1966. The flood devastated the city, resulting in catastrophic loss of life and property, according to scholar Robert Clark. His book takes us through the painstaking recovery and restoration of many works of art damaged in the flood. Moreover, around the city, you’ll see plaques marking the river’s water levels in November 1966.

Historian Larry A. Silver tells us disaster struck Florence and its artistic treasures yet again in the early 1990s. In fact, in 1993, a bombing occurred in the vicinity of the Uffizi. Scholar Tim Jepson tells us the bombing claimed the lives of five people, and severely damaged or destroyed the Uffizi’s walls and several artworks. Moreover, Jepson tells us the motives for the attack remain mysterious except perhaps to destabilize Italian politics and society.

One thing is certain: Florence is not just a city shaped by the artistic, cultural, and intellectual spirit of the Renaissance. Rather, you could say Florentines channeled those Renaissance-era achievements to help shape the future of both Italy and Europe as a whole.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our article on the best Florence tours to take and why.

Where To Stay in Florence

Florence has a small historical center packed with iconic landmarks to explore. Plan where to stay in the best neighborhoods in this beautiful city.