Irish food is as much political as it is dependent on Irish climate and produce from the land and sea. You’ll find the diet is largely made up of grains, sliced-and-diced meat, root vegetables, and Atlantic seafood (especially shellfish). So, for your enjoyment, come and see what kind of top foods to try in Ireland should hit your list!

Pro Tip: If you’re planning a trip to Dublin, consider checking out our Dublin tours. We run tours of The Cliffs of Moher, Giant’s Causeway, Titanic, and more!

The Best 15 Foods and Dishes to Eat In Ireland

The Emerald Isle has some of the best food offerings in Europe, especially in the capital of Dublin. You’ll find chefs in Ireland have perfected other European cuisines – particularly à la française – but have a tendency to leave Irish dishes behind. This is understandable, as Ireland’s food has always been about survival over anything else: – trying to fill oneself as much as possible without wastage (because during the famine, there was nothing left to waste). Understanding this, then the overuse of oats, grains, and breads in Irish food start to make more sense.

Just in case you were worrying, culinary Ireland still plays the classics. If you’re traveling to Ireland, you’ll absolutely find Irish stew and potato dishes, except chefs now incorporate foreign ingredients to enhance the blandness of former recipes. Perhaps this makes Irish cuisine not as traditional anymore, but at least Irish food is now tasty!

As you’ll also see in this guide, many indigenous dishes are actually single foodstuffs. The focus is on types of breads, cheeses, and producers. You may have to hunt these items down outside a restaurant in some cases, but like all things, anything worthwhile is never within one’s immediate grasp.

15. Irish Soda Bread

There are two reasons for why Irish soda bread transpired in the 19th century. Firstly, it was when bicarbonate soda arrived to Ireland through a Frenchman called Nicolas Leblanc. The second reason, was when the Irish heard about the Native American way of making bread, where they used wood ash (a natural soda) to leaven bread, instead of yeast. Consequently, Irish soda bread rose to stardom during the Irish famine, as the ingredients needed were few and cheap (flour, bicarbonate soda, salt, and buttermilk).

Today, you can find Irish soda bread all over Ireland. This bread knows no class boundary either, as both traditional pubs and Irish Michelin-starred restaurants will proudly serve it. Personally, I love to use soda bread as vehicle to mop saucy dishes like fish chowder and Irish stew. You can simply cut a slice, smother it in creamy butter, and then run it around your plate like a toy car on a Scalextric.

Where to get Irish soda bread: Ballymaloe Hotel and Restaurant in Cork

14. Dublin Coddle

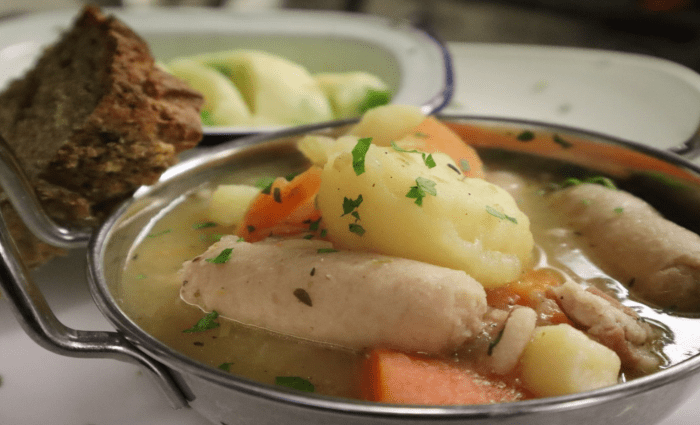

Dublin coddle is a specialty for the working class hero, derived from the French word caudle, meaning to parboil or lightly stew. The dish originated in the 1700’s when crops were poor and food shortages prevailed. As such, there is no official recipe for coddle – only the leftovers, or whatever’s at hand are directly thrown into the pot.

Historically, coddle was eaten on Thursdays, with the intention of using the last of the meat before a meatless Friday (a common ritual back then for Catholic families). Generally speaking, though, coddle will contain sausages, oats, carrots, and potatoes.

In 2021, modern Irish society is far removed from eating this meal. After all, it’s no cheesy pizza or ice-cream sundae. Yet coddle is vital for Irish tourism and heritage. People who knock it simply don’t understand its purpose! Like any national food, it once fed the bellies of our hungry ancestors, rooting them and giving them strength to work the fields.

In fact, if you are Irish and living abroad in a big city, you should always come home to a bowl of coddle, just so you don’t get carried away with yourself.

Where to get Dublin coddle: The Hairy Lemon in Dublin

13. Waterford Blaas

The precious blaa is a gift from French refugees who settled in southeastern Waterford during the 1600s. The name blaa is an Irish misunderstanding of the old French word for flour blanc. To this day, Waterford locals still love blaas so much, that you cannot hunt one down after midday. Currently, the population of Waterford (53,504) eats about 12,000 blaas per day!

To get your hands on such a jewel, restaurants like Hatch and Sons in Dublin serve in-house blaas with ham. However, most of the time, you can only get them as a standalone item from a bakery, or convenience store. Walsh’s bakehouse in Waterford is an institution for the textbook blaa, which should be soft and pillowy, with a dusting of flour on top.

In my old schooldays in Waterford, I would scurry into the canteen to snap up the last remaining blaa during recess. I would rip it open in the middle, lather on butter, and then crush in some buffalo-flavored Hunky Dory’s (Irish potato chips). Absolutely delicious.

Where to get a Waterford blaa: Walsh’s Bakehouse in Waterford

12. Boxty

Boxty is an Irish potato pancake. The dish comes from the province of Ulster, which is located in the center and north eastern parts of Ireland. Similar to Indian latkes, a boxty is made of finely grated potato that’s fried. The difference, however, is that boxty is smoother in appearance and looks like a fat omelette from afar.

The dish was traditionally eaten by the Irish for breakfast, or else for tea, which is another way of saying early dinner at around 5.30 pm. Not many places serve boxty commercially in Ireland except for The Boxty House in Dublin.

Incidentally, The Gallaghers (the family-owned business behind The Boxty House) were featured in an episode of Somebody Feed Phil on Netflix. In this episode, Phil visits Ireland and does an excellent job of accurately capturing the country and even our tasty boxty!

Where to get a traditional boxty: Gallaghers Boxty House in Dublin

11. Beef and Guinness Stew

Ireland’s best known dish has been around in its most basic form since the Anglo-Norman raids of The Iron Age. Back then, blacksmiths were fashioning cauldrons for cooking, which was perfect for stews and such. Over time, more ingredients were added to make it the beef and Guinness stew it is today.

At the start, cheap cuts like mutton were added, then barley for filler. In the 16th century, potatoes somehow managed to come over from their native Peru. So, into the stew they went. Guinness was added a century later. The reason for adding a stout like Guinness is that it tenderizes the meat. Beef and Guinness stew should never be greasy and is meant to be broth-like rather than congealed or gravy-ish.

You can find beef and Guinness stew in any traditional pub around Ireland. The Guinness Storehouse does a lovely rich and thick version with mashed potato on top. The Celt pub does a more customary version, which is also delightful. At the end of the day, the point of an Irish stew is to insulate you against the harsh elements of winter in Ireland.

Where to get beef and Guinness stew: The Celt in Dublin

10. Bairín Breac

Bairín Breac, also known by its Anglicized name as barmbrack, is a sweet bread with sultanas and raisins. The round loaf is reserved for Irish Halloween (Samhain), which is an ancient Celtic event. The long-standing tradition is to treat bairín breac like a fortune telling device.

You stuff the insides with trinkets: to receive a coin in your slice symbolizes good fortune; getting a ring means you’ll marry within the year; a pea says you won’t marry; a stick means your spouse will beat you; and a rag foretells bad luck and poverty.

In terms of the recipe, bairín breac is akin to Irish soda bread in that it’s made with bicarbonate soda and tastes slightly fermented. It’s best served warm with butter, alongside a cup of Irish tea with milk and sugar. As bairín breac is a festive treat, you won’t get it year round, but if you’re vacationing here in October, you can easily nab a bairín breac from any Irish supermarket.

I would go all out and buy one from Fallon & Byrne, which is Ireland’s version of Whole Foods. You’ll love this item on our list of top foods to try in Ireland.

Where to get barmbrack: Fallon & Byrne in Dublin

9. Crúibín

Crúibín, or “crubeen” are pig’s trotters, or pig’s feet. In days gone by, the Irish would boil crúibín, batter, and fry them, before devouring the foot whole like a corn dog. The idea of crúibín sounds rotten, but they are actually fairly easy to eat and similar in taste to ham hock. Irish Michelin-starred restaurants like The Lady Helen serve deconstructed crúibín (as pictured above in the form of the fried ball).

This style of crúibín is not uncommon for restaurants today, as it’s definitely the most aesthetically pleasing way of consuming the delicacy. In the real world, old-style crúibín are about as popular as Dublin coddle, but its cultural importance outshines the demand. As we know, regional cuisine is not just for our taste buds, but also for nostalgia, survival, and belonging.

If you are someone trying crúibín for the first time (old-style, warts n’ all), then it will probably look, and taste, a lot like “meh.” However, if you think back to your youngest self, habitually eating from your own culture – perhaps it was mom’s polenta, dad’s egg rolls, or a grandparent’s curry goat – remembering how you felt will soon make you satisfied about why you ordered crúibín in Ireland over a nice cheeseburger.

Where to get crúibín: Lady Helen Restaurant in Mount Juliet Estate, Kilkenny

8. Tayto Sandwich

It’s fast becoming obvious that Irish food is heavy on carbs! During the Irish famine, stodgy, filling food made sense, as there was little of it available. However, there’s no excuses now. All the same, the modern-day Irish would be nowhere without a good Tayto sandwich. So you know, Tayto is an iconic Irish brand of potato chips. They are so admired that the country even has a Tayto theme park. “Tayto” is short for potato, but is never used colloquially.

Some people have formed cultural debate around whether Tayto’s Irish rival (King crisps) is better, but I’ll let you decide for yourself. In saying that, the best way to eat Tayto is to purchase the holy trinity: a multi pack of Tayto, Brennan’s bread, and a tub of Kerrygold butter. The rest is self explanatory.

It’s also appropriate to swig on a Club Rock Shandy with your Tayto sandwich. For those unacquainted, Rock Shandy is an Irish soft drink invention. It mixes Irish versions of Fanta and Sprite together.

Where to get a Tayto sandwich: any local supermarket will stock Tayto, Brennan’s Irish bread, and Kerrygold butter

7. Irish Coffee and Baby Guinness

Irish coffee was created by an Irish airport chef called Joe Sheridan in 1943. He felt sorry for passengers who were delayed through the night and set out to make them a comforting drink. Once travelers descended upon his coffee concoction, the rest was history! Sheridan published his coffee recipe in the style of a limerick (a type of Irish poem, whereby every second sentence must rhyme). Here’s how his iconic recipe goes:

‘Cream – Rich as an Irish Brogue

Coffee – Strong as a Friendly Hand

Sugar – Sweet as the tongue of a Rogue

Whiskey – Smooth as the Wit of the Land.’

The trick for getting the cream to stay afloat in an Irish coffee is to slightly whisk it, then pour the cream down the back of a spoon. You can also substitute whiskey for Irish Baileys liqueur to double up on the richness of the drink.

In similar flavor profiles, another noteworthy drink is Baby Guinness. This is a creamy cocktail shot, which was created by two Englishmen some time ago. Baby Guinness is meant to resemble a tiny pint of Guinness. To make a shot, you do three parts coffee liqueur (Kahlúa or Tia Maria) to one part Irish cream (Baileys), spooned over the top.

Where to get an Irish Coffee: Vice Coffee Inc. in Dublin. Where to get a Baby Guinness: any well established pub in Ireland should know how to make one

6. Black Pudding

Black pudding is a blood sausage that comes from Ireland and also the United Kingdom. It’s made from pork or beef blood, with the inclusion of animal fats, oats, and barley. As with all sausage preparation, the mixture is put into an intestinal casing, before being boiled and then hung out to dry.

Many fine dining chefs use black pudding in their food since the iron-rich savoriness offsets delicate flavors like scallops or white fish. Tangy foods and dairy also pair well with black pudding, namely fruit chutneys and blue cheese.

There are black pudding producers all over Ireland. Southwest Cork, in particular, makes the highest quality black pudding. So, if you see Clonakilty black pudding on any menu or in any supermarket, this is the brand to go for. The familiar response of “Black pudding sounds disgusting” always lurks, but everything will be okay if you just don’t think about what’s in it.

Black pudding equals great taste. Old Irish men, or “aul fellas,” as we like to call them, sit down in the pub and eat raw black pudding with their pint of Guinness. A near liquid diet, packed with nutrients!

Where to get black pudding: John Keogh’s gastropub in Galway. Oak Fire Pizza in Cork

5. Colcannon and Champ

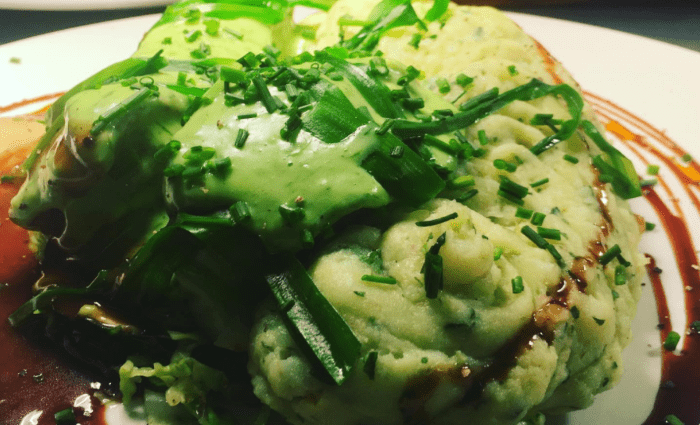

Colcannon and champ are two potato dishes that originated in the 16th century. They materialized soon after the first potato was planted in County Cork by Sir Walter Raleigh, an English aristocrat. A quick side note, however, is to say that some potato enthusiasts don’t believe this.

One alternate theory posits that the potato came to Ireland on a Spanish Armada ship after it crashed off the coast. At the end of the day, colcannon and champ are still going strong in Ireland, despite the potato enigma.

To make colcannon at home, you just cream some mash and fold in chopped cabbage, or kale. Champ is also creamed mash but with chopped nettle or scallions (green onions). Culturally, the two dishes were always made to celebrate the first harvest of potatoes. In Irish restaurants, they like to serve colcannon or champ with corned beef, boiled ham, or white fish.

Where to get colcannon and champ: Cistín Eile in Wexford

4. Regional Oysters

There are two common oysters available within Ireland. You have the native flat oyster and the Irish rock oyster. Irish people have been eating oysters for over 4,000 years, but its commercial cultivation started later in the 12th century. Irish oysters have remained in abundance due to the country’s vast coastline and salty bogland.

Today, Ireland has 130 oyster farms worth over €44 million. In terms of regional choice, northwest Donegal and southeastern Waterford produce 60% of all oysters in Ireland.

A purist will say you can only eat these mollusks au naturel, but they can be served in all kinds of ways. The Irish like to down oysters with a pint of Guinness or else throw on a dash of tabasco sauce. Other times, oysters are best eaten with pickled onion or a wedge of lemon.

My favorite approach to eating Irish oysters, however, is Korean-style with a hint of kimchi. This can be ordered at Yamamori restaurant on Bachelor’s Walk in Dublin.

Where to get oysters in each province: Rossmore oysters from Cork in Elbow Lane, Kelly oysters from Galway in Locks Windsor Terrace, Woodstown bay oysters from Waterford in The Reg, Kish Fish oysters from Dublin in Kish Fish seafood market.

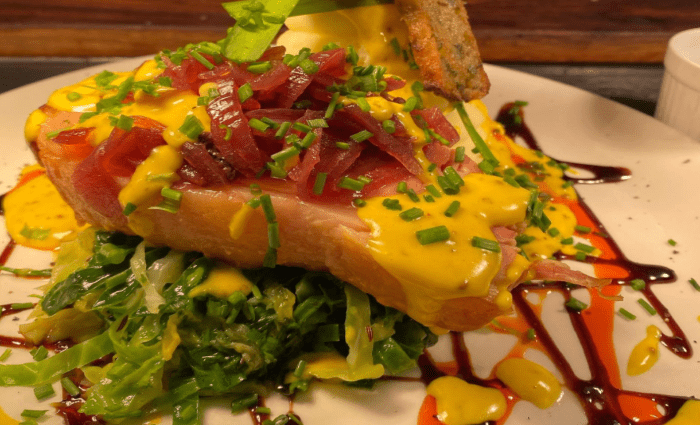

3. Bacon and Cabbage

Bacon and cabbage is a simple Irish dish that calls for a shoulder of boiled bacon. It’s always served in slices at dinnertime with spuds (Irish slang for potato), as well as with cabbage and white parsley sauce. The dish evolved during the 19th century when Irish immigrants went to the United States and subbed bacon for corned beef.

In Ireland, the OG bacon and cabbage is still consumed daily, especially in the midlands. There are also modern variations on bacon and cabbage, which I see as a big improvement. Particularly in the sauce department.

I grew up coughing on lumps of flour in my white parsley sauces, but now cooks have started to finesse this by cutting the heaviness with dollops of French mustard or hits of citrus. Ordering bacon and cabbage is a kind of must-do, when in Ireland, so don’t skip this top food to try in Ireland.

Where to get bacon and cabbage: Cistín Eile Wexford

2. St. Tola Goat Cheese

St. Tola is an Irish cheese of the late 1970s, and it comes from a small farmstead in County Clare. The success of St. Tola is down to the farm’s breed of goats (Saanen, British Alpine, and Toggenbury). The name itself comes from St. Tola of Clonard, who was the patron saint of toothaches in Ireland.

To describe this goat’s cheese, well, it’s yum. It’s soft like a spread and milder than most goat cheeses. You can find St. Tola in Irish restaurants, gastropubs, and supermarkets, either vacuum sealed, presented inside a fried ball, or plopped around a garden salad. There are other famous Irish goat cheeses like Ardsallagh and Fivemiletown, but St. Tola is my unfaltering favorite.

Where to get St. Tola goat cheese: The Boxty House in Dublin

1. Fifteens

Fifteens is a sweet slice of dessert from Northern Ireland that uses marshmallows, condensed milk, Graham crackers, desiccated coconut, and glacier cherries. This dessert is named so because it needs fifteen of every ingredient. You don’t ever hear of it in the Republic of Ireland, but it’s a classic for locals in the north.

Similar to a lot of Ireland’s cuisine, fifteens can only be homemade or bought in a convenience store. The confectionery is hassle-free in terms of preparation. So if you decide to make fifteens at home, you can simply bungle everything onto a tray before leaving it to set in the fridge for a couple of hours, then finito!

Where to get fifteens: French Village Bakery in Belfast