The Crusades were a 200-year experiment in holy branding, power politics, and long-distance logistics. The wars redrew maps, rewired trade (hello sugar, spices, and paper), and left scars that still shape how East and West see each other. This timeline cuts through the popular myths and famous names to show the wild detours, backroom deals, and jaw-dropping wrong turns that changed the world.

Quick Context of The Crusades

Before we dive into the timeline, let’s set the stage:

What Were the Crusades?

The Crusades were a series of religiously sanctioned wars fought between Latin Christian Europe and Muslim powers in the Eastern Mediterranean from 1096 to 1291. They began after Pope Urban II called on Christians to “liberate” Jerusalem, but the wars were never just about religion—they mixed faith with politics, land grabs, and power plays.

What Was Life Like During the Crusades?

Life was hard for the average person, with most people only living into their thirties. Religion shaped nearly every aspect of daily life, and without mail or newspapers, news rarely traveled beyond your town. When the pope appeared, it wasn’t just a visit—it felt like a glimpse of God himself.

What Was the World Like During the Crusades?

This was before the printing press, gunpowder weapons in Europe, and the Black Death. While Europe was still climbing out of the early Middle Ages, the Song Dynasty flourished in China, and the Maya civilization was still active in Central America. The Crusades were one part of a much bigger global story.

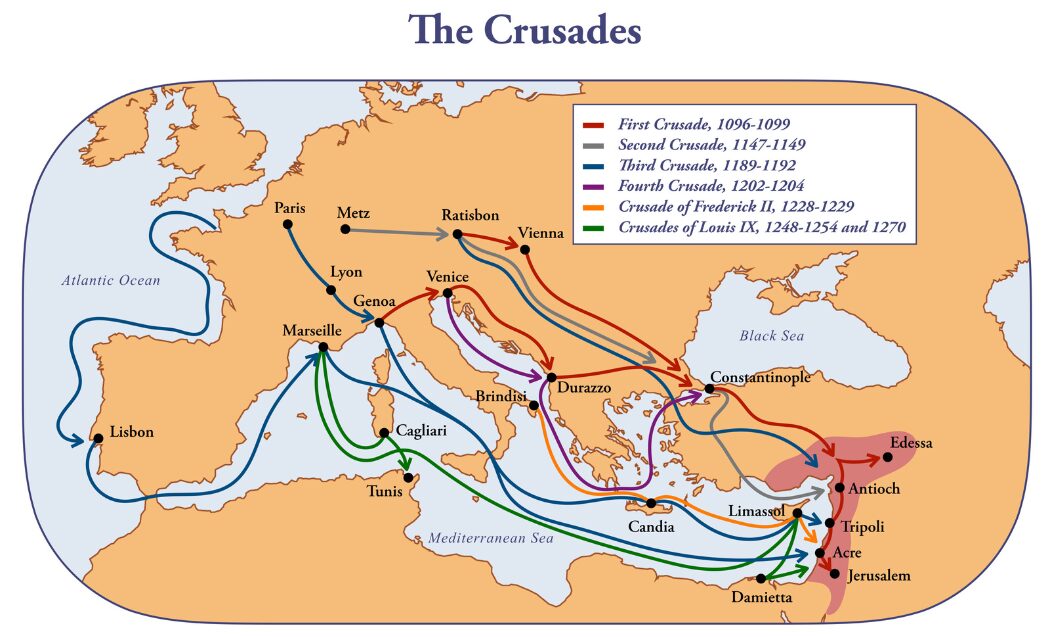

Where Did The Crusades Take Place?

The main theater of war was the Levant—roughly today’s Israel/Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan—with major campaigning routes through Anatolia (modern Turkey). Crusaders marched thousands of miles to get there, turning the wars into grueling armed pilgrimages. Imagine a medieval road trip where hunger, disease, and exhaustion killed more people than swords did.

What Were the Crusades About?

Officially, they were framed as holy wars to defend or reclaim sacred land. In reality, they were just as much about politics, trade, and personal ambition. Many crusaders were younger sons of nobles with no inheritance, so fighting in the Holy Land was their shot at fortune and glory.

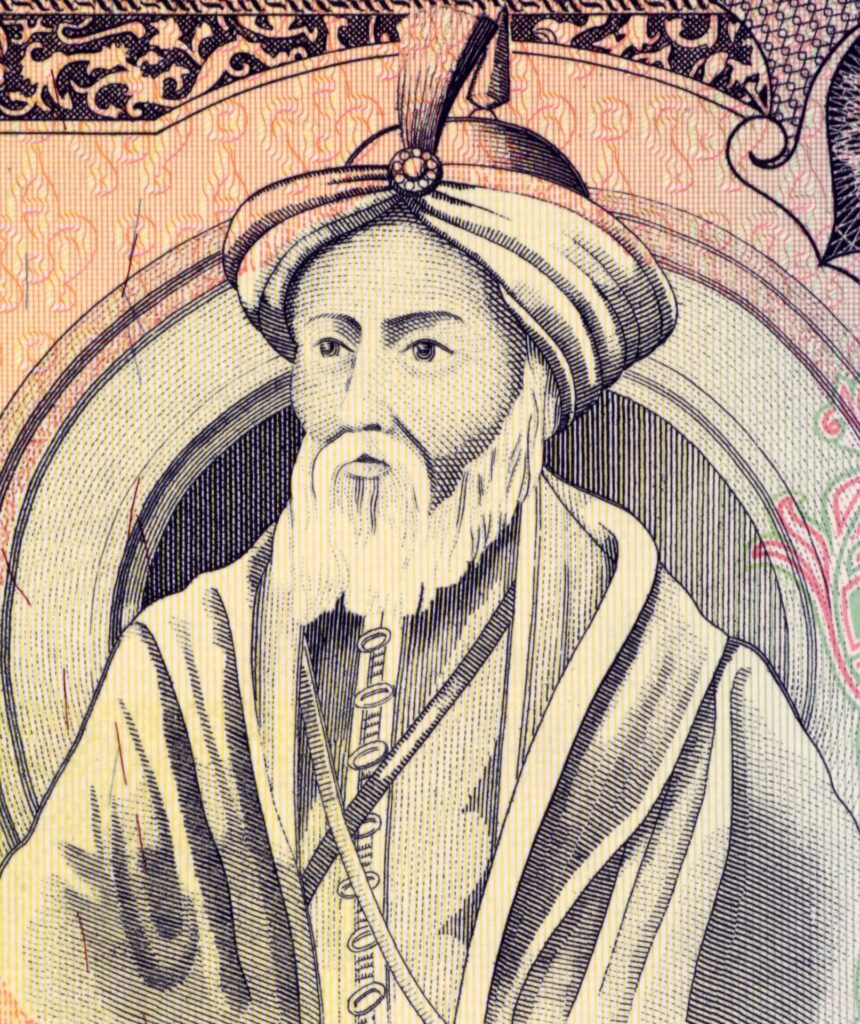

Map of the Crusades

A Timeline of the Crusades

The First Crusade (1096–1099): Against All Odds

Answering Urban II’s call, tens of thousands set off for Jerusalem—knights, mercenaries, peasants, even whole families. It took some people a year just to reach Constantinople (modern Istanbul). Against the odds, and thanks to political divisions among Muslim powers, the crusaders stormed Jerusalem in 1099.

It was a famously bloody siege—contemporary accounts describe streets ankle-deep in blood. Out of this victory, four crusader states were set up in the Levant (modern Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine).

Why it matters: The First Crusade succeeded where later ones failed. It cemented the idea that holy war could change borders, politics, and history.

The Second Crusade (1147–1149): Europe Fumbles

The Muslim reconquest of Edessa, one of the crusader states, triggered a new wave. This time, European royalty led the charge—Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany. But coordination was a mess, supplies ran short, and the whole thing ended in failure.

Why it matters: The Second Crusade showed that crusading wasn’t a guaranteed win. The dream of easy glory in the East began to crack.

The Third Crusade (1189–1192): Richard vs. Saladin

Europe’s great kings set out to reclaim Jerusalem, but the crusade quickly unraveled. Barbarossa drowned before battle, Philip went home after quarreling with Richard, and Richard pushed on, capturing Acre and winning at Arsuf. Yet despite his victories, he could never secure the holy city—his army lacked the numbers and supply lines to hold it even if he did.

In 1192, Richard and Saladin signed the Treaty of Jaffa: Jerusalem remained Muslim, but Christian pilgrims could visit without fear. Richard secured coastal strongholds to protect crusader states, and Saladin maintained his prestige while avoiding further bloodshed.

Why it matters: The Third Crusade proved that victory wasn’t always about conquest. Through negotiation, two rivals carved out a compromise that shaped the politics of the Holy Land for years.

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204): The Wrong Turn

This one was supposed to target the Holy Land, but it famously got sidetracked. Due to money problems and Venetian meddling, the crusaders ended up sacking Constantinople, a Christian city.

Here’s how it happened: The crusaders had promised the powerful Venetians a massive sum for transport but couldn’t pay. In a shocking turn, the Venetians offered them a deal: attack the Christian port of Zara (today Zadar, Croatia) to settle the debt, and then sail to Constantinople to install a friendly ruler on the throne. The crusaders agreed, and they looted, burned, and set up the Latin Empire, which controlled Constantinople until 1261.

Why it matters: It was one of history’s biggest “how did we get here?” moments. The event deepened the split between the Catholic West and Orthodox East.

The Sixth Crusade (1228–1229): Diplomacy Over Swords

Twenty-five years after the Fourth Crusade’s disaster, Europe’s leaders were tired of fighting. Enter Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. A man excommunicated from the Church, he set out for the Holy Land with a small army. He was a master of diplomacy and, working through interpreters and some Arabic learning, did something unprecedented. Instead of fighting, he negotiated with the sultan of Egypt, al-Kamil.

Frederick and al-Kamil, two men who understood the political game, worked out a deal. In a treaty, al-Kamil agreed to hand over Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Nazareth to Christian control in exchange for an truce against the Sultan’s enemies. Frederick entered Jerusalem peacefully and crowned himself king, fulfilling the crusading vow without a single battle.

Why it matters: The Sixth Crusade proved that a political settlement could achieve what centuries of violence couldn’t. It was an epic “win” for the Crusaders, but it was also a sign that the nature of crusading had changed forever.

The Later Crusades (13th Century): Desperation and Decline

After Frederick II’s diplomatic victory, later crusades felt increasingly desperate:

- 1212 — The Children’s Crusade: Thousands of young people set off for the Holy Land, but most never returned.

- Mid-13th-century campaigns: Various attempts were made to regain lost ground, but they lacked unity and resources.

- Louis IX of France: One of Europe’s most pious kings, he failed twice—once in Egypt (1249–1250) and again in Tunisia (1270), where he died of illness.

By this stage, enthusiasm was waning. Crusading no longer carried the same glamour, and many in Europe were turning their attention to local politics, trade, and new conflicts closer to home.

Why it matters: The later crusades revealed the limits of the movement. Without strong leadership or popular momentum, crusading had become more of a political inconvenience than a holy cause.

The End of the Crusades (1291): The Fall of Acre

In 1291, the Crusades reached their final breaking point. Acre, the last major Crusader stronghold in the Holy Land, was attacked by the Mamluks, a powerful Muslim dynasty. After a brutal siege, the city fell, and with it, any real Christian presence in the Levant disappeared. Although later popes called for more crusades, Europe no longer had the strength or unity to mount them.

Why it matters: The fall of Acre wasn’t just a battlefield loss—it marked the end of two centuries of crusading. It left behind bitterness and mistrust between faiths but also cleared the way for new trade routes, shifting politics, and changing balances of power. The Holy Land was no longer the centerpiece of European ambition.

The Impact: What the Crusades Left Behind

The Crusades may have ended in military failure, but their impact on European life was immense. For over two hundred years, they opened up a previously isolated continent to the cultures, ideas, and goods of the East. The world changed forever, even if not in the way the popes had planned.

- New Luxuries: Crusaders brought back a taste for sugar, which was initially used as a medicine and was so rare it was called “white gold.” They also popularized a wide array of spices like pepper and cardamom, making European food a lot more interesting.

- A Cleaner World: The crusaders noticed that Arabs bathed often and used smooth, olive oil-based soaps. This exposure to Arab hygiene helped change bathing habits in Europe, which were, well, not great at the time.

- The Paper Trail: Crusaders helped introduce paper to Europe, eventually replacing the more cumbersome and expensive parchment. This simple shift made it easier to record and share information, paving the way for the Renaissance and the printing press centuries later.

Beyond these cultural shifts, the Crusades left a deep legacy of bitterness and mistrust. The conflict cemented a view of “otherness” between the Christian and Muslim worlds, and the brutal violence left wounds that have yet to fully heal.

So, what did the Crusades really achieve?

They failed to establish a lasting presence in the Holy Land and drained Europe of vast resources. But they also kick-started a globalized world, connecting East and West in ways no one could have imagined. In the end, they proved that a holy cause could inspire both epic journeys and catastrophic violence—a lesson that still echoes through history.