Think Milan is only about the latest in fashion or the hustle and bustle of its modern urban center? Well, think again as this city also can claim a bevy of great works of art. Check out Milan’s most famous must-see works of art below!

This article isn’t meant to replace a guided visit—quite the opposite! Reading up on an attraction will make a guided tour more memorable and interesting! You will impress your travel partners and engage more with the guide. Check out our guided tours of Milan!

25 Must-See Masterpieces in Milan

Milan is renowned as a business hub and the pulse of fashion. But not everything in Milan is about the latest trends in fashion and finance. In fact, the city boasts a rich cultural history as evidenced by its world-class museums. As a result, there is no shortage of great art to appreciate in Milan.

For starters, you’ll find Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. Unquestionably as art historian Ian Chilvers explains, it is Milan’s most famous art treasure. However, Milan claims art treasures produced over many centuries and by some of the world’s most recognizable artists. From Renaissance legends like Michelangelo to modern greats including Antonio Canova, Milan’s churches, museums, and galleries deserve mention among Europe’s great art destinations.

So, interrupt your shopping spree to check out this must-see art in Milan!

25. St. Bartholomew Flayed

Marco d’Agrate | 1562 AD | Marble | Milan Cathedral (Duomo di Milano)

You probably don’t expect to walk into a cathedral and get an anatomy lesson. But that is exactly the case in Milan. Without question, this saintly statue is an unusual and striking piece. Scholars Katrin Rupp and Nicole Nyffenegger explain it depicts St. Bartholomew holding a bible in one hand, and part of his flayed skin in the other.

Indeed, it is the latter part that reveals the impressive quality of this statue. In fact, as Chilvers points out, the statue depicts a strikingly realistic impression of the human body. As such it demonstrates sculptor Marco d’Agrate’s commitment not just to art but to the pursuit of knowledge. In other words, it is a very fitting if unusual piece of Renaissance art.

Moreover, Marco d’Agrate knew he created a sculptural masterpiece. In fact, the statue bears the inscription: “Non me Praxiteles, sed Marcus finxit Agrates.” As art historian Dana Arnold explains, d’Agrate included this to tell viewers this was his work and not that of legendary classical Athenian sculptor Praxiteles.

24. Rondanini Pietà

Michelangelo | 1552-1564 AD | Marble | Sforza Castle Gallery (Castello Sforzesco)

You’ll find one of Michelangelo’s later works at Milan’s Sforza Castle. In fact, as art historian Elizabeth Munro explains, the Rodanini Pietà is the artist’s last unfinished work.

Chilvers tells us Pietà depicts the Virgin Mary holding the dead Christ’s body. Furthermore, arguably the most famous of these is Michelangelo’s Pietà installed at the Vatican’s St. Peter’s Basilica. Michelangelo, as Munro explains, returned to the subject in works found in Florence and Milan.

However, Michelangelo’s Milan Pietà is very different from his earlier creations in Rome and Florence. In fact, Chilvers explains, the sculpture is almost modern in style and that it foreshadowed the coming mannerist movement in art.

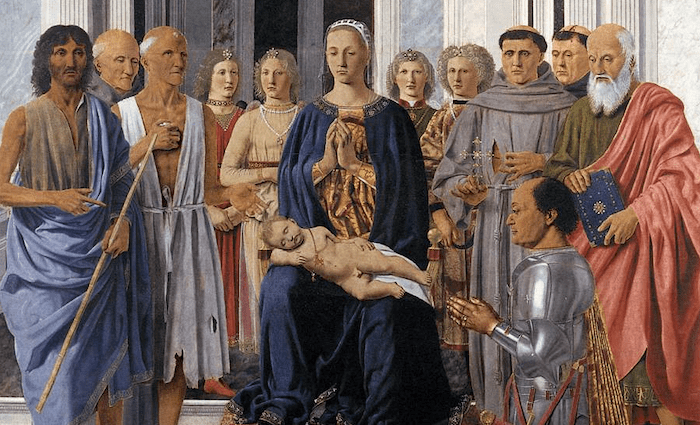

23. Madonna and Child with the Saints, Angels, and Federico da Montefeltro (Brera Madonna)

Piero della Francesca | 1472-1474 AD | Tempera on panel | Brera Gallery (Pinacoteca di Brera)

Alternatively known as the Montefeltro Altarpiece. As art historian Craig Staff tells us, this name derives from the guy who commissioned the work from Piero della Francesca: Duke of Urbino Federico da Montefeltro.

Here we see the first of a common theme in this thread: depictions of the Madonna (Our Lady) with the infant Jesus. However, as Staff points out, it is likely a deeply personal scene for Montefeltro. In fact, the Virgin’s facial features suggest that she resembles the duke’s recently deceased wife, Battista Sforza. She died shortly after giving birth to the noble couple’s son Guidobaldo. Staff argues for this interpretation because of Federico’s presence in the painting, kneeling before the work’s holy figures.

Moreover, art historian Keith Christiansen points out the Brera Madonna illustrates Piero della Francesca’s fascination with architecture, light, and geometry. But perhaps most importantly, as Staff’s interpretation shows us, what sets this piece, and many Renaissance-era works of Christian art apart is the very human qualities of holy figures.

Furthermore, as art historian Ian Chilvers notes, Renaissance art celebrated not just the beauty of human beings but also had no issue placing holy figures amongst our natural world.

22. Theseus Killing the Minotaur

Cima da Conegliano | c. 1505 AD | Oil on panel | Museo Poldi Pezzoli

Stepping away from religious scenes, we also have examples of famous scenes from mythology. For example, in this case, we see the story from Greek mythology of Theseus slaying the Minotaur on the island of Crete. As art historian Dana Arnold tells us, mythological stories were favorites of Renaissance artists.

Moreover, Paul Cartledge tells us that Theseus is one of the most famous figures from Greek mythology. A mythical king of Athens, Cartledge says ancient Athenians credited Theseus with many of the city’s famous characteristics. However, Theseus’s struggle with the fearsome Minotaur on Crete in an effort to end the Athenian tribute to the Minoans is his most famous event.

The artist behind this painting is Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano. According to Chilvers, Cima da Conegliano emerged as one of the leading Venetian painters between about 1490 and 1510. Moreover, Chilvers explains Cima da Conegliano drew inspiration from the work of another famous Venetian artist: Giovanni Bellini.

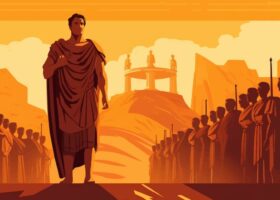

21. Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Lodi (May 10, 1796)

Andrea Appiani | 1800-1801 AD | Tempera on canvas | Galleria d’Arte Moderna

Art historian Jonathan Keates tells us Andrea Appiani was northern Italy’s most famous painter at the close of the 18th century. So, it is fitting that Appiani painted one of the time’s most famous people: Napoleon Bonaparte.

In the days before instant communication, painters played a major role in spreading popular images of famous people and events. According to historian Andrew Roberts, few harnessed the power of such art better than Napoleon. Moreover, Appiani’s painting captures a famous event in the Napoleonic legend of the 1796 Battle of Lodi between the French and Austrians in northern Italy.

Here Appiani shows a twenty-something then-General Bonaparte leading the French army across the Adda River to crush retreating Austrians. Moreover, as historian David A. Bell explains, Napoleon’s victory at Lodi enabled his conquest of Milan within days. Eventually, Napoleon would crown himself King of Italy at Milan’s Cathedral.

At the same time, supporting Napoleon worked out well for Appiani. For instance, historian Spencer Di Scala says during Napoleonic rule in Italy, Appiani served as a leading official and played a major role in cultural affairs.

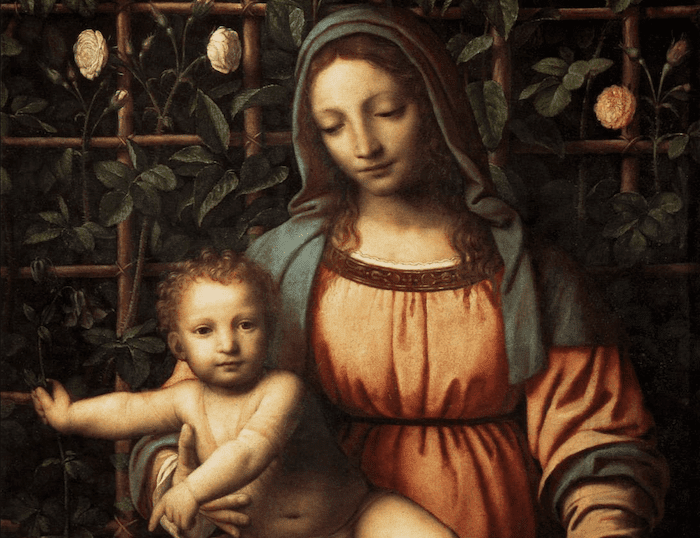

20. Madonna del Roseto (Madonna of the Rose Bush)

Bernardino Luini | c. 1510 AD | Oil on panel | Pinacoteca di Brera

Art historian Ian Chilvers tells us that Luini emerged as one of Milan’s most famous artists in the 16th century. Moreover, many of Luini’s compositions were influenced by Leonardo da Vinci. Art historian Luisa Arrigoni notes that this piece is one of Luini’s early masterpieces.

However, little is known about the painting’s origins or its original collection information. According to Arrigoni, scholars believe Luini completed the work in Pavia where he was working in the early 16th century.

Here Luini returns to a familiar image of the Madonna with baby Jesus. Arrigoni mentions that Leonardo’s influence is clear through the infant Christ’s pose and the Virgin’s facial features. Again, we see the very human qualities of these holy figures. At the same time, Arrigoni points out the attention to natural elements like plants and flowers in the background.

Aas Chilvers points out, all these features stress the shift in Renaissance Christian art emphasizing the beauty of humanity and nature. Finally, the Brera holds several notable Luini paintings.

19. Portrait of Alessandro Manzoni

Francesco Hayez | 1841 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

Art historian Jonathan Keates says it took no less than fifteen sittings to produce this portrait of one of Milan’s (and Italy’s) cultural icons. Moreover, as historian Chris Duggan explains, Manzoni made a rare exception for Hayez as he resented sitting for portraits. Why is that such a big deal?

For starters, Manzoni is considered one of the founding fathers of modern Italian culture. In fact, as historian Spencer M. Di Scala points out, Manzoni’s novel The Betrothed (I promessi sposi) emerged as a rallying point for proponents of a unified Italy in the 19th century.

Moreover, Keates says Hayez does not get much credit for his portraits compared to the more famous historical paintings. However, as Keates explains, Hayez painted many of 19th century Italy’s most famous people including Manzoni.

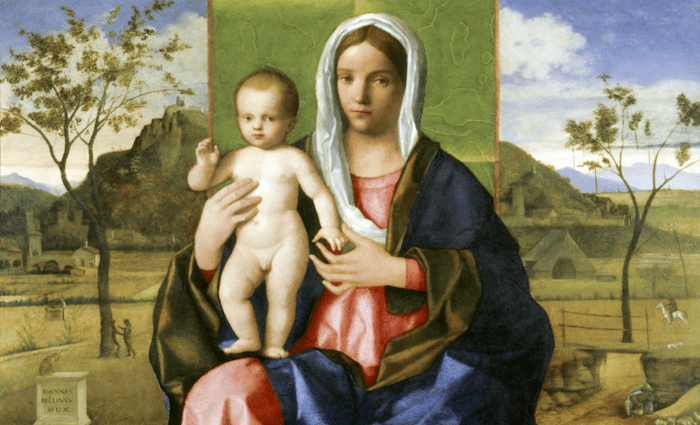

18. Madonna and Child

Giovanni Bellini | 1510 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

According to Arrigoni, this canvas dates to 1510, when the artist was around 80 years old. By that point, few figures in Venetian Renaissance art were as famous as Giovanni Bellini. The center is dominated by the figure of the Virgin enthroned. However, Luisa Arrigoni argues that perhaps the painting’s true focus is the vibrant landscape behind the figure of the Madonna.

Moreover, Arrigoni points out that restoration work carried out in the 1980s revealed very little preparatory drawing. Imagine needing basically no practice or guide to paint a masterpiece! Chilvers tells us Bellini came from a family of talented Venetian artists. For instance, Giovanni’s brother Gentile and father Jacopo were also celebrated artists.

17. Madonna of the Book

Sandro Botticelli | c. 1480-1481 AD | Tempera on panel | Museo Poldi Pezzoli

While perhaps more famous for some mythological themes, here Botticelli tackles a familiar theme in Christian art: the Madonna and Child. However, here we see the Virgin Mother and Child reading a book.

According to art historian Luisa Arrigoni, the book’s decorations suggest it is the Book of Hours, a prayerbook for laymen popular in Europe between the 13th and 16th centuries. Botticelli again aims to present the holy figures in a human and natural way. At the same time, Arrigoni points out, including that prayer book gives the image an everyday life quality.

16. Portrait of the Young Antonio Canova

Giuseppe Bossi | 1810 AD | Oil on canvas | Galleria d’Arte Moderna

According to historian Chris Duggan, Giuseppe Bossi briefly held the distinction of being northern Italy’s most famous portrait artist. In this painting, Bossi captures a youthful likeness of modern Italy’s leading sculptor, Antonio Canova.

While Canova’s most famous works were executed for various European patrons—from Napoleon to popes, he also had an American connection. In fact, as art historian Xavier F. Salomon explains, Thomas Jefferson was a fan of Canova’s sculptures.

As a result, when North Carolina representatives sought an artist to produce a statue of George Washington, Jefferson lobbied for Canova to get the job. Ultimately, this statue of George Washington stood among Canova’s final works produced in his lifetime.

Sadly, the marble originally brought to the North Carolina Statehouse in 1821 was destroyed in an 1831 fire. However, a plaster copy survives. Another artist created a marble sculpture replica in 1970.

15. A Fight in the Arcade

Umberto Boccioni | 1910 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

Alternatively called A Riot in the Gallery, there is a lot of chaotic stuff going on in this painting. However, as art historian Luisa Arrigoni explains, that is the point Boccioni drives home. Specifically, as scholar William Davies points out, Boccioni depicts a throng of upper-class people breaking out in hysteria in Milan’s most famous shopping arcade.

Indeed, words like “action” “speed,” and “fight” certainly played an important role in Boccioni’s vocabulary. Boccioni emerged as one of the leading figures of the Futurist movement in early 20th century Italian culture. Futurists, as scholar William Davies explains, vehemently rejected traditional views on art and the past writ large.

Moreover, as historian Spencer Di Scala points out, Futurists celebrated conflict. Thus, many proponents later became associated with Mussolini’s Fascist regime.

Boccioni, however, did not live to see that dark chapter of Italy’s history. In fact, as historian Spencer Di Scala points out, Boccioni’s devotion to Futurism’s central tenants of action and celebration of conflict led to his death while serving in the Italian army during WWI.

14. The Madonna of the Cherubim

Andrea Mantegna | C. 1485 AD | Tempera on panel | Pinacoteca di Brera

According to art historian Luisa Arrigoni, Venice’s Church of Santa Maria Maggiore initially held this Mantegna piece. Beyond that Arrigoni notes, there is a lot of mystery surrounding this work.

In fact, as art historian Joseph Manca says, for many years the painting was attributed to Giovanni Bellini. Moreover, Arrigoni points out that the Duchess of Ferrara possibly commissioned Mantegna to execute this piece for a private chapel. What we do know is that it depicts the Madonna and Child.

13. St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria

Gentile & Giovanni Bellini | 1504-1507 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

This massive canvas once graced the reception room of the Scuola Grande di San Marco in Venice. According to art historian Luisa Arrigoni, the building housed one of Venice’s most prestigious and powerful confraternities.

As art historian Tom Nichols explains, it is easy to spot the political significance of this canvas through the various symbols of St. Mark and his church in Alexandria. However, it also reveals the imperial might and broad connections of Venice’s commercial and maritime empire. For example, art historian Luisa Arrigoni notes the obelisks and minarets in the canvas would have been familiar to Gentile. In fact, Gentile Bellini even worked for Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II in the 1490s.

Art historian Ian Chilvers explains that Giovanni completed the painting after his brother Gentile’s death. Gentile apparently included this detail in his will. Moreover, art historian Luisa Arrigoni notes that we don’t know how much was unfinished at Gentile’s death.

12. The Agony in the Garden

Veronese (Paolo Caliari) | 1582-1583 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

Art historian Luisa Arrigoni tells us that Brera acquired this canvas in 1808. Moreover, Arrigoni points out its confirmation as a Veronese work through sources at Venice’s Santa Maria Maggiore. In fact, Arrigoni continues, Veronese was likely commissioned by a Venetian noble to adorn a chapel there in the early 1580s.

Furthermore, art historian Richard Cocke notes that Veronese focuses on the human qualities of Jesus. As Cocke points out, Veronese captures the moment when Christ learns of the Passion awaiting him and falls in the arms of an angel. Once again, we see raw human emotion and qualities attached to religious figures. As art historian Ian Chilvers tells us, such depictions would have been unthinkable a few centuries earlier.

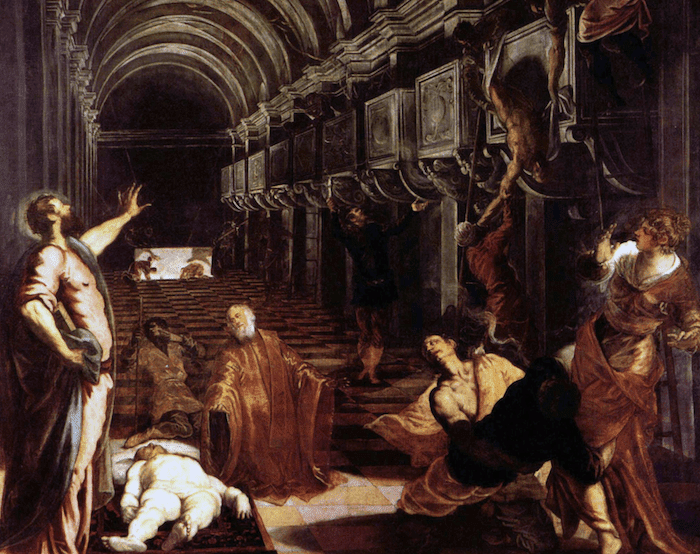

11. Discovery of the Body of St. Mark

Tintoretto | c.1562-1566 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

Alternatively called Finding of the Body of St. Mark. Legendary artist Tintoretto was commissioned by Tommaso Rangone, leader of Venice’s Scuola di San Marco to paint a cycle of episodes related to the life of their patron saint. As art historian Luisa Arrigoni explains, the Brera holds one canvas from this cycle.

Art historian Sandrina Bandera Bistoletti says the canvas depicts the moment when St. Mark’s body appears to the Venetians as they remove remains from tombs. Furthermore, Bandera Bistoletti notes Rangone’s presence in the painting. When you pay to commission a painting you have a way of finding a place in the finished product.

10. The Other Last Supper

Peter Paul Rubens | c. 1631-1632 AD | Oil on panel | Pinacoteca di Brera

According to art historian Luisa Arrigoni, this Rubens painting formed part of a group of Flemish paintings donated to Milan in 1813 in exchange for art seized from the city by Napoleon. Moreover, art historian Sandrina Bandera Bistoletti explains the painting originally came from a church in Malines (Mechelen, present-day Belgium).

Furthermore, art historian Mark Lamster tells us Rubens dominated Flemish Baroque painting in the 17th century. What is more, Lamster explains Rubens was a man of more than exceptional artistic talents. In fact, Rubens enjoyed great acclaim among European courts as a respected diplomat.

Although it is obviously not the most famous depiction of the Last Supper displayed in Milan, it is nonetheless among the Brera Gallery’s celebrated pieces.

9. La Pergola

Silvestro Lega | 1868 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

Alternatively called After Lunch. According to art historian Ian Chilvers, Silvestro Lega is among modern Italy’s greatest painters. As Chilvers explains, Lega had firsthand experience in the making of modern Italy. In fact, as art historian Norma Broude points out, Lega served as one of Giuseppe Garibaldi’s volunteers during the ill-fated 1848-49 Roman Republic. As a result, art historian Jonathan Keates tells us many of Lega’s paintings involved military scenes.

However, Lega is best known as one of the leading figures of the Macchiaoli movement in Italian art. Macchiaoli as art historian Jonathan Keates explains the group’s name derives from the word macchia (literally spot or blotch). Moreover, art historian Christopher Masters says the Macchiaoli were deeply patriotic. Finally, Masters points out the group anticipated Impressionism and had many ties to French realist artists.

In this canvas, Lega depicts a tranquil after-lunch scene at Piagentina outside Florence. Art historian Luisa Arrigoni explains that Lega moved there in 1861 and hosted many Macchiaoli painters.

8. Trivulzio Madonna

Andrea Mantegna | 1494-1497 AD | Tempera on canvas | Civic Museum of Ancient Art, Sforza Castle

This large altarpiece derives its name from its previous collector between 1791 and 1935. Mantegna depicts the Madonna enthroned surrounded by a group of saints and angels. Below Mantegna depicts angels surrounding an organ. According to art historian Joseph Manca, the organ refers to the Olivetan Church of Santa Maria in Organo at Verona.

While originally, Mantegna’s work belonged to this church in Verona, today it is displayed at the Sforza Castle. Originally built in the 14th century, the Duke of Milan Francesco Sforza greatly enlarged the fortifications during the following century. According to historian Spencer Di Scala, the castle was once one of Europe’s largest fortifications. Instead of housing nobility, today the castle is home to several museums and art collections.

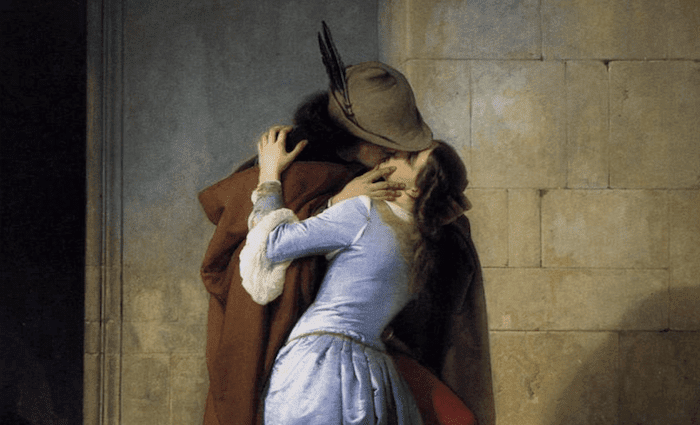

7. The Kiss

Francesco Hayez | 1859 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

Art historian Jonathan Keates tells us that Francesco Hayez was a leading figure of Italian Romanticism. Moreover, his paintings captivated patriotic Italian nationalists during the mid-19th century struggle for unification. Indeed, if the Italian Unification movement (Risorgimento) had an iconic visual representation, many scholars say Francesco Hayez’s The Kiss would be it.

Regardless, as art historian Laura L. Watts argues, Francesco Hayez emerged as the movement’s leading artist. Here Hayez captures a passionate farewell between a young man and woman. According to scholar Sarah White Wilson, Hayez appears to show the couple engaged in a stolen kiss in a forbidden place.

On the other hand, the painting is identified for its connection to Italian Unification. As Laura Watts explains, Italian patriots felt the painting captured the Risorgimento spirit and sacrifice for the cause of a unified Italy. Furthermore, Hayez produced several versions, including a watercolor displayed at Milan’s Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

6. Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker

Antonio Canova | 1802-1806 AD (Original) | Marble (Original); Bronze, Plaster Copies | Pinacoteca di Brera; Multiple Locations

Antonio Canova was a big deal in early 19th century Europe. And that was good for him because historian Andrew Roberts says this sculpture embarrassed Napoleon. Apparently, Napoleon blushed at his nude appearance which looked more like a chiseled classical god than the rather portly guy he became in the early 1800s.

Today you’ll find two different versions of this famous Canova work at the Brera. The first is a gilded bronze situated in the courtyard. The second is the best-preserved plaster copy housed in the collection. However, you’ll find the marble original at London’s Apsley House. In fact, historian Andrew Roberts tells us the building’s famous former owner (the Duke of Wellington) frequently had guests hang their umbrellas from it.

5. Il quarto stato (The Fourth Estate)

Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo | 1898-1901 AD | Oil on canvas | Museo del Novecento

One of the most iconic paintings pertaining to modern Italian history and to several wider social and political movements. For example, art historian Jonathan Keates explains this painting became a popular symbol for various European socialist movements in the 20th century.

Pellizza depicts a confident group of striking laborers. Historian Spencer Di Scala tells us the artist drew inspiration from the upheavals brought by industrialization in late 19th and early 20th century Italy.

Moreover, art historian Anna Maria Damigella says Pellizza produced several iterations on this theme before arriving at this iconic scene. For example, Pellizza executed the painting La Fiumana (The River of Humanity) between 1895 and 1898. Today you’ll find this prequel work on display at the Brera.

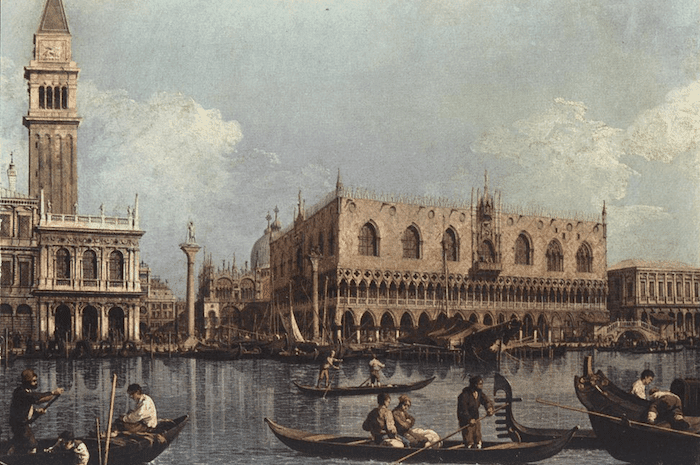

4. View of St. Mark’s Basin from the Punta della Dogana

Canaletto | 1740-1745 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

Here we have a slice of Venice in Milan. According to art historian Luisa Arrigoni, this is one of Canaletto’s favorite views of Venice. As such, Canaletto painted numerous versions of this cityscape. Furthermore, Arrigoni tells us this is a companion piece to another Canaletto depiction of Venice on display in the same room at the Brera.

Moreover, art historian Katharine Baetjer says Canaletto earned fame by painting Venetian scenes for visiting Grand Tourists during the 18th century. As a result, his work became particularly popular in Britain. With his popularity growing, Canaletto thus moved to Britain for several years.

3. Pietro Rossi

Francesco Hayez | 1818-1820 AD | Oil on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

Historian Chris Duggan tells us critics instantly hailed this Hayez painting as revolutionary when it debuted at the Brera in 1820. However, Duggan explains revolution and politics were the last things on the young painter’s mind. For instance, Duggan says Hayez embarked on numerous affairs and loved to party. He also did all he could to evade military service during the Napoleonic Wars.

Nevertheless, Italian nationalists saw a powerful message in this Hayez painting. Specifically, Duggan says critics were drawn to the agony exhibited by the painting’s central figures: Pietro Rossi and his family.

Indeed, Rossi is torn between taking command of a Venetian army marching off to war and remaining with his wife and children. Duggan says many Italian nationalists felt they were confronted with a similar dilemma of fighting or staying with their families.

The painting’s full title is Pietro Rossi, lord of Parma, despoiled of his estates by the Scaligers, lords of Verona, while sent to defend the castle of Pontremoli and to take command of the Venetian army, which was due to move against his enemies, his wife and two daughters tearfully begging him to refuse the command. Very catchy.

2. The Lamentations over the Dead Christ

Andrea Mantegna | c. 1480-1490 AD | Tempera on canvas | Pinacoteca di Brera

Art historian Joseph Manca suggests that this work was done late in Mantegna’s life as it was found in his collection at the time of his death. Furthermore, Manca suggests it is possible Mantegna saved it for his own personal prayer and devotion.

Moreover, Manca describes the scene as “an intense vision of Christ’s suffering and death.” It depicts three figures mourning Christ, Saint John, Mary, and Mary Magdalene. Furthermore, the body of Christ is laid on a marble slab.

However, art historian Ian Chilvers says what makes Mantegna’s work so striking is his technique of foreshortening. It is a technique involving a figure’s depth and viewing angles. Manca says Mantegna’s work is a classic example of Renaissance-era foreshortening. By situating Christ’s body in this position, Manca says it makes viewers see a more human, earthly side of Jesus. In other words, this is quintessential Renaissance art separating it from earlier religious art.

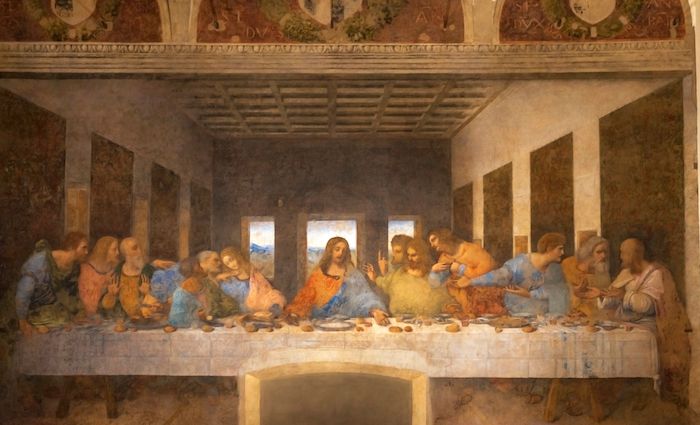

1. The Last Supper

Leonardo da Vinci | c. 1495-1498 AD | Tempera on gesso, pitch, and mastic | Santa Maria delle Grazie

Scholars like art historian Ian Chilvers suggest this is in fact the world’s most famous work of art. Indeed, even after five centuries, there is tremendous demand to see Leonardo’s masterpiece. However, it is not just its enduring popularity that makes Leonardo’s work so famous.

Moreover, it is the unique technique Leonardo deployed as well as the various efforts to ensure its preservation. According to Ian Chilvers, Leonardo had no patience for the slow methodical fresco method of painting. So, instead, Leonardo employed an experimental technique called sfumato. Art historian Christopher Masters tells us sfumato comes from the word fumo (smoke) and means “faded away.” It refers to the subtle blending of tones and colors so that they melt together without recognizable transitions. Thus, it is truly unlike anything we have seen to this point.

However, this technique led to the work’s rapid deterioration. As a result, succeeding centuries included numerous restoration efforts. For example, art historian Michael Ladwein notes that celebrated painter Giuseppe Bossi undertook restoration work in the early 19th century. A controversial restoration occurred in 1999.

Today you’ll find about as many scholarly articles dedicated to the science behind the painting’s preservation as art history scholarship. Nevertheless, Leonardo’s work remains one of the world’s most famous must-see artworks.

And there’s still so much to see in Milan! You may want to keep delaying your shopping trip.

Where To Stay in Milan

Milan is a small city with plenty to explore from iconic landmarks to a vibrant art and design scene and old-world charm. Plan where to stay in the best neighborhoods in this beautiful city.