The Dutch Golden Age produced some of the greatest works of art in the Western Hemisphere. Following hard-won independence from Imperial Spain, the middle class, enriched by trade and inspired by art from around Europe, commissioned portraits, still lifes, and landscapes. This patronage allowed the brilliance of Dutch artists to flourish and gave the world these top works of art at the Rijksmuseum.

Pro Tip: Planning your visit to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam? Bookmark this post in your browser so you can easily find it when you’re in the city. Check out our guide to Amsterdam for more planning resources, our best Amsterdam and Rijksmuseum tours for a memorable trip, and how to visit the Rijksmuseum.

Top Things To See at the Rijksmuseum

As famed art historian and author W. H. Janson puts it, “Holland produced a bewildering variety of masters and styles. From the collector’s mania in the 17th century came an outpouring of artistic talent comparable only to early Renaissance Florence.”

The Rijksmuseum, the National Museum of the Netherlands, is a soaring celebration of Dutch art. This guide highlights the top works of art at the Rijksmuseum, works you won’t want to miss, and pieces that are not only stunning examples of the styling of each artist but which provide context for hundreds of years of history. It layers the stories of the artists, their subjects, and how they interrelate with one another and continue to influence our world today.

Be sure to appreciate the building itself, designed by Pierre Cuypers to house this dazzling collection of Dutch masterpieces. Visiting the Rijksmuseum, you’ll get the sensation of walking through a cathedral dedicated to a mortal brilliance that feels touched by the divine.

Not ready to book a tour? See our Amsterdam Guide for more info.

11. Still Life with a Turkey Pie

Pieter Claesz I 1627 I Oil on Panel I Gallery of Honor

This might not look like a still life of our typical turkey dinners at Thanksgiving, but that’s because Claesz layered it with symbolism, meaning, warning, and even a hidden self-portrait.

The Dutch know still lifes, one of the most iconic forms of high art you can find. In fact, “still-life” comes from the Dutch stil-leven, a phrase that has multiple meanings, including “still-model.”

Still Life with a Turkey Pie is one of Claesz’s finest works. It captures each subject so carefully that it seems you could reach out and pluck a grape from the canvas. From a technical standpoint, the piece is a marvel. Note his command of texture, his use of light and reflection, and his restraint in the use of color. Also, be sure to notice the artist’s self-portrait, hidden in the reflection on the silver wine decanter.

This piece, however, is so much more than a showcase of Claesz’s artistic mastery. Still Life with a Turkey Pie tells a complex story. Ingvar Bergstrom’s classic, “Dutch Still-Life Painting in the 17th Century” explains that each item in the scene is deeply symbolic and conveys multiple layers of religious and social messaging.

Still-life paintings conveying this level of opulence remind the viewer that these are earthly delights and that we are mortal. You can find the theme of man’s mortality in most still-lifes, either represented overtly with a skull or hourglass or more subtly with dead game or fish.

Layered Meaning in the Painting

The fruit bowl is full of subtext. The apples recall Adam and Eve’s fall from grace. The grapes and vine represent Jesus Christ. The broken bread and wine are Christ’s communion. The cracked walnuts scattered on the table are a common symbol for redemption and the hard walnut shell represents the crucifix.

The religious subtext continues: the lemon shows luxury, but with a sour taste, reminding us of the evils of gluttony and greed. The oyster, a known aphrodisiac, represents sinful lust.

Yet Claesz’s table shows us so much more than the traditional and expected religious symbolism. This table setting reveals a family with wealth and connections to the wider world. The rolled paper shows expensive pepper and salt spilling out. The turkey pie was baked with spices like cinnamon, mace, and ginger, which were expensive and extravagant.

A final detail to note in this still life is the nautilus cup, slightly right of center. Claesz uses this gorgeously detailed shell-chalice to represent not only wealth but the mysterious and exotic.

While Claesz wanted you to feel the dread of your impending mortality with his turkey pie, you might just feel hungry. The good news is there are excellent cafés and a highly-rated restaurant right in the museum.

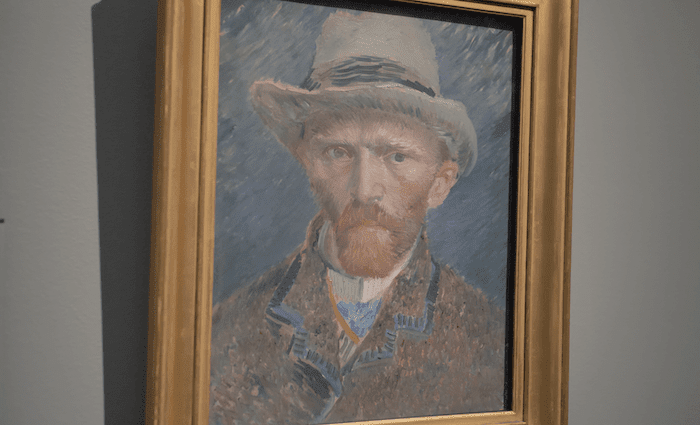

10. Self Portrait

Vincent van Gogh I 1887 I Cardboard I Room 1.18

Vincent van Gogh needs no introduction, and it seems only right that he figures prominently in this guide of Rijksmuseum’s giants of Dutch art. While we largely associate van Gogh with France, where he lived, painted, and tragically died, he was in fact, as his name suggests, Dutch.

This hero of the modernist movement had strong ties to his mother country. He was hugely influenced by Dutch masters, including Frans Hals, and was incredibly close with his brother Theo and other family members.

The Rijksmuseum has several van Gogh works, but it’s the self-portrait that looms largely in room 1.18. It seems appropriate that the Dutch National Museum displays one of its most famous son’s paintings of himself.

They say that van Gogh used himself as a model to save money, but when you look at this piece, that explanation feels unsatisfactory. This is not a man looking to experiment with brush strokes while looking in a mirror. This is a man searching for himself.

Joost Meerlo was struck by the same thought as he wrote his article, “Vincent van Gogh’s Quest.” He writes, “in his self-portraits especially, we find van Gogh in search of his own identity. ‘Who am I?’ is his continual question. We may call it the manifestation of early muted feeling – the inner notion of being incomplete.”

While admiring the brush strokes and the dazzling use of color, also see the man. See van Gogh, a man with deep sadness, fear of loneliness and obscurity, one with great generosity, and a savage sense of humor. A man on a journey to know himself, just as we all are.

Check Out Our Best Amsterdam Tours

Top Rated Tour

Amsterdam in a Half Day by Bike

Explore the Dutch Capital with a local guide by bike. Beginning in the heart of Amsterdam, head through the Jordaan district and the city’s largest park. Ride along the network of canals and then sample some of Amsterdam’s best beers. See the Rijksmuseum, Heineken, Amsterdam Central Station, and more. Bike Rental Included.

(4)

Starting at €30

Likely to Sell Out

Royal Rijksmuseum Tour with Skip the Line Access

Known for its impressive collection of over 8,000 works by the greatest Dutch artists, the Rijksmuseum is the National Museum of the Netherlands. With your expert art historian guide, see the best of the museum including Rembrandt’s famous The Night Watch. Learn the stories and discover the hidden gems of these artists and their works on this fun and informative Rijksmuseum tour in Amsterdam.

(8)

Starting at €59

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our Amsterdam Guide for more resources.

9. The Threatened Swan

Jan Asselijn I c.1650 I Oil on Canvas I Gallery of Honor

From a technical standpoint, The Threatened Swan is a beautiful piece, full of force, movement, strength, and fury. The swan is rising up, fierce and protective of its egg. The dog, in the lower-left corner, suggests the immediate threat. Because we view it from almost the same perspective as the dog, we sense that the threat to the swan is immediate, ubiquitous, and may even come from us, the viewer.

Asselijn’s work is valuable for the technical skill and strength of the subject, but what makes it a must-see when visiting the Rijksmuseum is that this swan is an allegory. It tells the story of one of the most pivotal moments in the history of the Golden Age.

The Story Behind the Threatened Swan

If you look closely, there are labels above each subject of the painting. The dog is the “Enemy of the State,” the egg is “Holland,” and the mighty swan is “The Grand Pensionary.” No one is sure who added these words, but it was done years after the painting was completed, probably around 1672.

Simon Schama’s excellent history of the Dutch Golden Age explains the storm of politics swirling in the second half of the 17th century. The labels reveal the major players. The dog is England and France, which declared war on Holland. The Grand Pensionary is Johan de Witt, the most powerful statesman in Holland from 1650 until his fall from power.

In 1672, France and England declared war. Holland saw horrific infighting between the powerful, republican de Witt, his ally and brother, Cornelis, and the House of Orange-Nassau.

A series of events led to what felt like the inevitable fall of the Dutch to the French, English, and some opportunistic German states. De Witt and his brother were blamed and violently assassinated in the street. In a macabre turn, their corpses were roasted as the mob turned cannibalistic.

The House of Orange then prevailed over a relatively peaceful transition of power and installed William of Orange, a monarch who would affect the future of all nations involved for generations to come. As you wander through the Rijksmuseum, you will see portraits of members of the House of Orange, as well as a portrait of Cornelis de Witt by Jean de Baen.

The swan, appropriated by defenders of the de Witt brothers, is a reminder (as all Dutch art seems to be) that no matter how powerful, we are all mortal.

8. The Merry Family

Jan Havicksz Steen I 1668 I Oil on Canvas I Gallery of Honor

The Merry Family draws you in with its exuberance and joy. It almost feels as if you should pull up a chair, light a long, slender clay pipe, and join in the singing. Steen’s painting of a family in revelry—men and women, children, and even a dog, partaking in bacchanal afternoon festivities, was typical of his style. Steen often portrayed common people in their everyday moments of levity, with round faces, pink cheeks, and full roemers (a large glass for drinks).

Steen, a prolific artist, supplemented his income by owning and running a boarding house and tavern. One wonders if many of his subjects were from everyday life – episodes of drunkenness he’d witnessed firsthand. As H. Perry Chapman concludes in his Jan Steen, Painter and Storyteller, Steen was, of all of the great Dutch masters, the one most adept at observing his surroundings and breathing life into everyday scenes of merriment.

Steen has a similar style to an artist we will discuss at length below, Frans Hals. They have the same spontaneity, ability to capture movement, and lively-looking subjects. They also shared the boldness to paint subjects in casual poses and even smiling at the viewer.

In The Merry Family, there seems to be just a hit of judgment. While the parents are rosy and joyous, in the foreground, an older child is allowing a much younger child to drink from the wine decanter. Cheeky young ones are smoking by the fire. The crucial message is written on a note hanging off the mantle: “as the old sing, so shall the young twitter.”

Steen seems to be saying with his tableau to enjoy a raucous, jubilant time together, but there are consequences. As the Dutch like to remind us, we’re mortal.

Notice The Drunken Couple and The Feast of St. Nicholas (also in the Gallery of Honor) for similar examples of Steen’s work. And then go find a full roemer for yourself.

7. Winter Landscape with Ice Skaters

Hendrick Avercamp I 1608 I Oil on Panel I Room 2.6

This is a favorite painting in the Rijksmuseum collection, mostly because it is a masterful collection of stories within one work.

Avercamp, born deaf and mute, was a well-respected artist of his day who was active during a period of transition in Dutch art. Landscapes, always a favorite subject in Holland, became moodier, more monochromatic. Artists experimented with bringing the horizon down lower across the scene and with icy, snowy winterscapes.

While snow scenes were common, Avercamp created something special with this work. If you stand in front of it long enough, you become immersed in his world. Avercamp spares us nothing—we get death, life, joy, fun, toil, love, and even some silliness.

At first glance, you see couples skating, some falling, and some laughing. There is a pointed juxtaposition between the festivities and the people working, toiling in the frozen snow. We are reminded that life is fleeting by the frozen corpse of a horse being consumed by a dog and some crows.

Look closely and you’ll see plenty of warmth in this painting. Notice a couple making love, a child running to his father with arms outstretched, women gossiping, and men playing a game that looks like hockey. There is even some humor, like the man immodestly relieving himself. In the left of the painting, it appears there is not just one bare bottom, but two. Avercamp, in a moment of vanity or fun, painted his own name as graffiti on the side of the shed to the right.

This painting is important as we tell the story of Dutch art through the ages. He shows us the increasing shift from the idealized landscapes of the Flemish style into something wholly new and specific to this time and place. He humanizes the landscapes and brings us in. While the fashion and technology are different, everyday work, play, and emotions are still true for us today.

6. Girl in a White Kimono

George Hendrik Breitner I c. 1894 I Oil on Canvas I Room 1.18

When Japan finally opened its borders in the mid-19th century, the Dutch joined the rest of the world in a frenzy for all things Japanese. Dutch artist, George Hendrik Breitner found himself especially captivated by Japanese woodcuts.

He worked with his favorite model, a local seamstress, Geesje Kwak, and painted her in at least twelve different positions, all wearing a kimono. Note that he melds the background and foreground into one, thereby making the painting feel as flat as one of the woodcuts.

Breitner was a well-respected and admired artist in his day. He was especially known for his paintings of street scenes and thought of himself as a painter of the people. He was an early advocate of the new, radical style coming from Paris, called Impressionism, and became a close companion of Vincent van Gogh.

The two artists worked together often and seemed to have an on-again-off-again friendship. While there was mutual respect, van Gogh was sometimes frustrated by Breitner’s art. He complained in a letter to his brother Theo in July 1883 that when Breitner was in a hurry, his work looked like strips of “old faded wallpaper.”

5. Morning Ride Along the Beach

Anton Mauve I 1876 I Oil on Canvas I Room 1.18

We move ever so slightly back in time to Anton Mauve’s subtly exquisite painting of a ride on the beach. Mauve, Breitner, and van Gogh were contemporaries and knew each other well. Van Gogh and Mauve were related by marriage. He often wrote about their friendship, but the two had a terrible fight over a prostitute. Mauve told van Gogh that he had a “vicious character.” Van Gogh turned around and walked away, the friendship over forever.

Despite his broken relationship with van Gogh, Mauve had a successful career capturing the Dutch countryside. He was especially well respected for his depiction of sheep and cattle. Interestingly, painters were compensated more for “sheep coming” than “sheep going.”

John Ruskin, a turn-of-the-century art critic, describes Mauve as “the sweet lyric artist of Holland.” His landscapes capture light and shadow, with a restrained, somber color palette. There is beauty but perhaps also sadness to his works. E. B. Greenshields described it: “he sees that man moves through his life like a shadow passing over the ground, and like it disappears and is forgotten, while nature is permanent and enduring.” As with many Dutch masterpieces, we are reminded, through the immutability of nature, of our own mortality.

Greenshields puts his finger on what makes us stop and drink in a Mauve painting. Mauve “captures the mysteriousness of nature, and this makes his pictures types of her different moods more than views of particular places.”

4. Landscape with Two Oaks

Jan van Goyen I 1641 I Oil on Canvas I Room 2.6

Van Goyen’s Landscape with Two Oaks is an important expression of a classic, idealized Dutch landscape. It has many of the attributes that we associate with the genre. It is monochromatic, displays moody colors, is balanced by a low horizon line, and showcases fine careful detail.

This landscape, though, is remarkable for what the subject represents. Van Goyen has many landscapes that romanticize the Dutch countryside with windmills and swampy low-lying areas. But this landscape is punctuated by the two massive, gnarled oak trees standing sentry.

These forms speak of power and isolation, almost a regal stance contrasted against a stormy, gray sky. The trees are deeply aged and scared, decayed (the Dutch: we all die), and yet they still stand.

Van Goyen made several versions of this same landscape but with different details. The people, dwarfed by the natural surroundings, change, as do the details in the distance. But the trees remain deep-rooted, proud, strong, and Dutch.

3. Portrait of a Couple, Probably Isaac Abrahamsz Massa and Beatrix van der Laen

Frans Hals I c. 1622 I Oil on Canvas I Gallery of Honor

It’s hard not to fall in love with this couple who are so clearly in love. The truth is, it’s hard not to fall in love with Frans Hals himself. Hals was a wildly successful portrait painter in 17th century Haarlem, a town that was suddenly and boisterously wealthy. He was so popular that he set his own terms and refused to leave Haarlem to paint his subjects. If they wanted him, they’d come sit for him in his studio. For some perspective, even Rembrandt traveled to his subjects when commissioned.

After galleries of stiff, formal portraiture, it’s refreshing to see a couple look affectionate and casual with one another. The lace is exquisitely painted, as is the detail of Beatrix’s large cartwheel ruff. Because this was a marriage portrait, the vine symbolizes steadfastness and the thistle at the groom’s feet represents male fidelity.

Frans Hals had a reputation for alcoholism and violence. While historians now largely debunk these tales of misbehavior, his image as a bad boy of Dutch art remains. A closer analogy, however, might be Andy Warhol: a stylist, nonconformist, adept at making art approachable, commercial, and softly satirical. After hundreds of years of formality, a Frans Hals subject looks directly at you and smiles.

Frans Hals painted the celebrities of his day—the rich, famous, and well-dressed. He captured the spirit of his city and his world—the emerging individualism and desire for status. As Peter Schjeldahl writes in his New Yorker article, “The Haarlem Shuffle,” “Hals’s panache [….] quickly charmed Haarlem, becoming emblematic of the city’s entrepreneurial zest and robust self-regard.”

Hals has been long celebrated. Edouard Manet, Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent, and Vincent van Gogh traveled to Holland specifically to study him. It feels like portraits in our current century continue to be influenced by his style. Hals seems the type who would have thought to paint Barack Obama sitting casually in a bush.

Modern-day viewers feel like they know this couple. Beatrix wears the pants in the relationship and Isaac had been in love with her for years from afar. Frans Hals has captured them in all of their young, joyous, pink-cheeked amour. And for once in this guide, a Dutch masterpiece does not include imagery to remind us that we are all mortal and die.

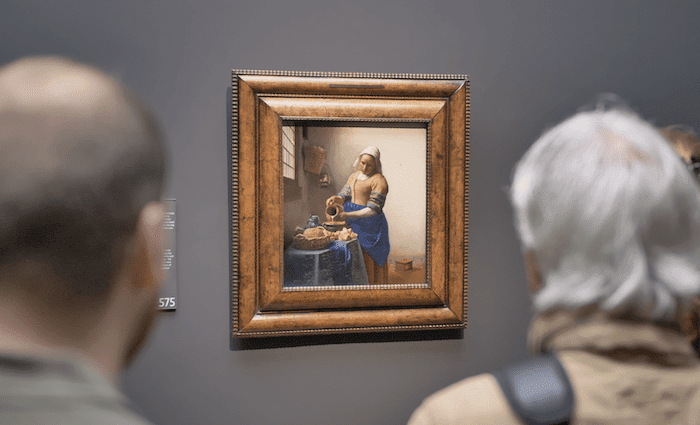

2. The Milkmaid

Johannes Vermeer I c. 1660 I Oil on Canvas I Gallery of Honor

Johannes Vermeer is another who needs little introduction. He and Rembrandt are the princes of Dutch art and the kings of Chiaroscuro. Here, with his Milkmaid, he communicates so much with such skill.

Start with the mathematics of the painting. You are drawn to the milkmaid and her hands, not just because that is where the action lies, but because Vermeer manipulated the angles of each object. Start at the window (where one pane is broken) and imagine a line going down at an angle. From there every object is in a triangle with a point focused on the girl’s hands. The use of color and shadow helps to draw the eye in.

Vermeer captured light and shadow by applying dots of color to show reflection. Notice the difference between the natural light peeking through the broken pane and the light filtered through the window that floods the white-washed room.

From there, pay attention to the details: the nail holes in the wall and the fact that the bread is not fresh, but crusty and stale. The girl’s worksleeves are pulled up and there is a slight tear in the seam on her shoulder. There is a foot warmer and a Cupid on the Delft tile at her feet.

While this all feels very straightforward, there is plenty of mystery. What is this milkmaid actually doing? Is she making bread pudding—a common and cherished Dutch dish? The ingredients are all there: crusty bread, milk, and a tankard with beer to use as a leavening agent.

But Vermeer’s ultimate object seems to ask, who is she? With her creamy complexion, her wide hips, and her strong, steady stance, she communicates a moral fortitude.

The world had seen kitchen scenes and milkmaids before. Both were favorite subjects of Dutch artists. But Vermeer introduced something wholly new and complex. We are curious about her; drawn to her. She radiates warmth in a cold kitchen. She promises maternal safety and offers subtle hints of sensuality.

The milkmaid transposes realism to become allegorical, a notion of something abstract and widely recognized and respected. Her dress keeps her humble, in contrast to classical depictions of themes like “honor” or “fidelity,” but we are sure that she is something or someone special. Ultimately that is Vermeer’s greatest gift, to elevate the common, mundane, and humble into the extraordinary.

Check Out Our Best Amsterdam Tours

Top Rated Tour

Amsterdam “Locals” Food Tour in the Albert Cuyp Market

Join your engaging local foodie guide on a journey through the over century-old “Cuyp”. With over 250 stalls, the market hosts the best of Amsterdam’s street food scene. Sample dishes that represent the history and culture of the city. From Pickled Herring prepared as it has been for centuries to Indonesian fusion dishes that represent the modern face of the city, eat the best of Amsterdam on this wonderful food tour.

(5)

Starting at €49

Likely to Sell Out

Royal Rijksmuseum Tour with Skip the Line Access

Known for its impressive collection of over 8,000 works by the greatest Dutch artists, the Rijksmuseum is the National Museum of the Netherlands. With your expert art historian guide, see the best of the museum including Rembrandt’s famous The Night Watch. Learn the stories and discover the hidden gems of these artists and their works on this fun and informative Rijksmuseum tour in Amsterdam.

(8)

Starting at €59

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our Amsterdam Guide for more resources.

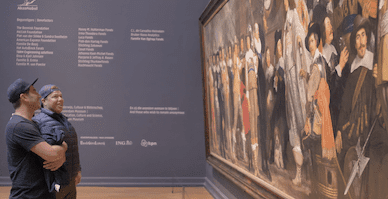

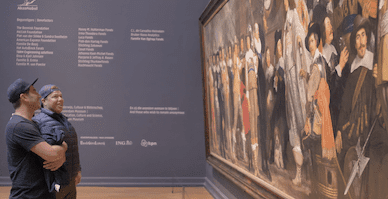

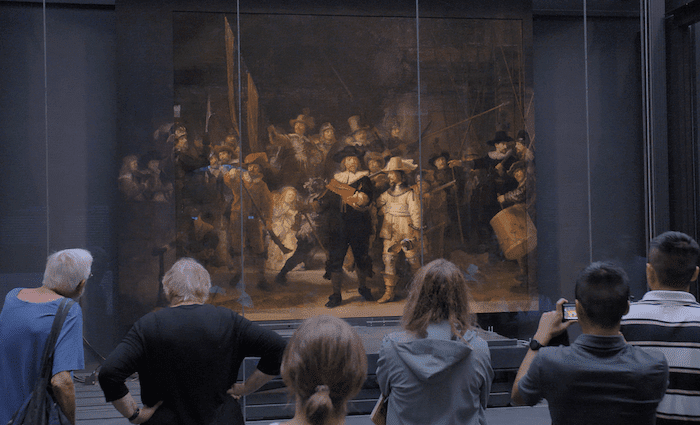

1. The Night Watch

Rembrandt van Rijn I 1642 I Oil on Canvas I The Night Watch Gallery

The Night Watch is the most famous artwork in the Rijksmuseum and one of Rembrandt’s largest and most iconic pieces. Commissioned by Amsterdam’s civic guard for their headquarters, it is, in the words of Jansen, “a virtuoso performance of Baroque movement and lighting.”

Not only is it a masterpiece of technical skill, but it is captivatingly lyrical. Rembrandt was a master storyteller and conveys infinite levels of subtext within his canvas. It starts with the act in the center of the painting. The Captain has just given his order to the Lieutenant but has yet to order his men. And at that moment, it’s as if we have burst in, catching everyone in a moment of action.

Men are loading weapons (one is even being fired), boys are running around, one with a helmet on that’s too big, a drummer is trying out his instrument, and the drum is frightening the dog. The painting looks loud and boisterous. The viewer feels the movement and can almost predict where a hand will land and where a foot will go next.

As Michael Bockemuhl writes in his book on Rembrandt, “the execution of the details alone — the splendidly gleaming metal, the shimmering cloth, the various pieces of equipment — and, even more so, the fashioning of the eloquent facial expressions, succinct gestures and dazzling lighting effects are artistic in the highest degree. The possibilities inherent in a depictive representation would seem to have been exhausted.”

This is a private moment for the civic guard. What makes the scene so incredibly appealing is that it is an instant frozen on the precipice of action. This is the civic guard as “individuals,” before the Lieutenant relays the order to march. It will be at that moment that they become the civic guard as a “collective.” It’s a celebration of both individualism and anticipation. We ask, is this a moment that is extraordinary or is this anticipation of the extraordinary?

Remember, though, that this is a portrait commissioned to show each individual member of the guard. Several years after the painting was completed, officials moved it to City Hall and large swaths of the panel were cut off. Experts suspect as many as 4-5 meters of completed canvas disappeared. The rumor is that while there should have been a hew and cry over the destruction of this masterpiece, there were enough soldiers and subjects unhappy with their depiction that they didn’t mind being cut out.

Luckily though, Captain Frans Benning Cocq (the subject at the center of the work) commissioned a copy of the painting. Because this copy still exists, experts have an idea of what the missing panels looked like. They are in the process of a massive project utilizing artificial intelligence to reproduce the panels and restore the original.

While looking at The Night Watch, as with so many works of art in this guide, one is transported into a world exclusively of the artist’s making.

Perhaps Vincent van Gogh says it best in his letter to his brother Theo in 1885, “Rembrandt goes so deep into the mysterious that he says things for which there are no words in any language [….] he could make poetry – be a poet, that’s to say, Creator.”

Where To Stay in Amsterdam

Amsterdam is a vast city with many areas to stay in, including beyond the downtown area. Choose a hotel near the top things you want to see in this beautiful old city.