“You can take the so-called ‘escape-proof’ jail—and they never built one—and I maintain if you put a man in it [he] can get out of it. They’re as smart as we are, so they can figure a way out. On the other hand, I can take two men with shotguns and a hundred inmates in an open field and keep those people there until they starve to death, or they run and I shoot ’em, and I have maintained security.”

– Warden Olin G. Blackwell

Pro Tip: It’s easier to organize your trip when you have all your resources in one place. Bookmark this post along with our San Francisco Guide for more planning resources, our best San Francisco tours for a memorable trip, and how to visit Alcatraz.

History of San Francisco’s Alcatraz

Alcatraz Island: The most notorious federal penitentiary in the United States. The worst of the worst criminals. An inescapable fortress—or so they thought. This mysterious fortress-turned-penitentiary has long captured the interest of Americans during its reign as the crème de la crème prison where men like Al Capone and James “Whitey” Bulgar darkened the halls.

But there is more folklore than reality about life on this prison island. In fact, the families who lived there loved it so much they referred to it as “the poor man’s Hawaii.” Let’s take a look at the history of Alcatraz and discover its true history and what life was really like on The Rock.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if San Francisco tours are worth it.

The Early History of Alcatraz

Though the early indigenous people in the San Francisco area were familiar with the rocky island, the first known exploration of the island happened by Spanish explorer Captain Alaya in 1775. The island was filled with birds of all kinds, especially the cormorant (similar to a pelican), so the island earned the name La Isla de los Alcatreces.

Richard Dunbar put together a great explanation of the early years of this tiny, strategic island in his book Alcatraz. Under the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United States acquired California, and as you could expect, the U.S. Army realized the strategic value of a rocky fortress in the middle of the massive San Francisco Bay.

Demolition and construction began in 1850 to make way for barracks, gun placements, and a lighthouse. Since the island was mostly rock, they hauled tons of topsoil in to make it habitable after blasting dynamite for more space. That topsoil sprouted new plant life including agave, blueberry bushes, honeysuckle, eucalyptus trees, and more.

Since the army built an impressive prison fortress, it was immediately used during the Civil War to house prisoners. Quite a long way to haul prisoners from the East Coast before the transcontinental railroad was completed! Treatment of prisoners proved brutal and solitary, so the island earned the name “Uncle Sam’s Devil Island.”

The army didn’t like the black eye reputation, so they made plans to shut down. Thanks to a new, nearby lighthouse and excessive maintenance costs, the army vacated Alcatraz in 1934.

Needless to say, it made an attractive opportunity for the Bureau of Prisons. Alcatraz remained empty for mere weeks before they moved in. Violent crime had blossomed in the 1920s and 1930s, and a place was needed to house the worst criminals.

Basic Facts About The Island and Prison

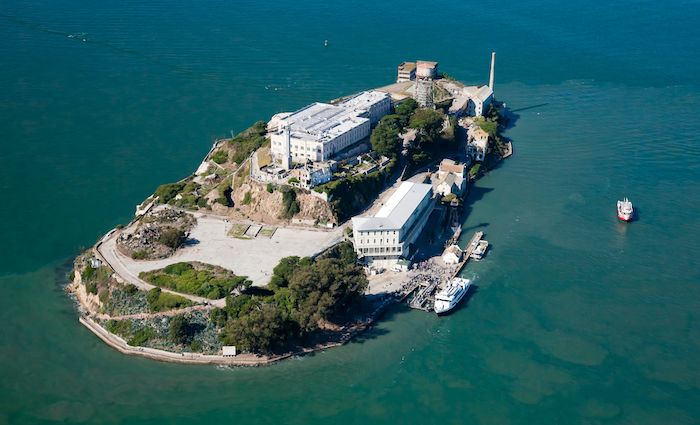

Alcatraz Island sits just 1.25 miles from the shore of San Francisco, yet the thick fog of the bay often obscures the view completely. At 22.5 acres, it’s roughly the same size as 17 football fields. Some sides of the island are 50-foot cliffs. Sharp agave plants would be the first to injure you if you fell off a cliff. The rocks at the bottom might maim you next, but the icy cold water was almost sure to do you in.

Jolene Babyak describes the prison island in her book Eyewitness on Alcatraz. The 3-story yellow prison took up most of the island, but there were also the barracks, apartments, and recreation hall for the numerous families and children who lived on the island full time.

Six towers watched over the prisoners. It took 12 minutes to get to shore by boat and in the early years, the boats only made nine round trips to shore each day. (Eventually they made 22 each day.)

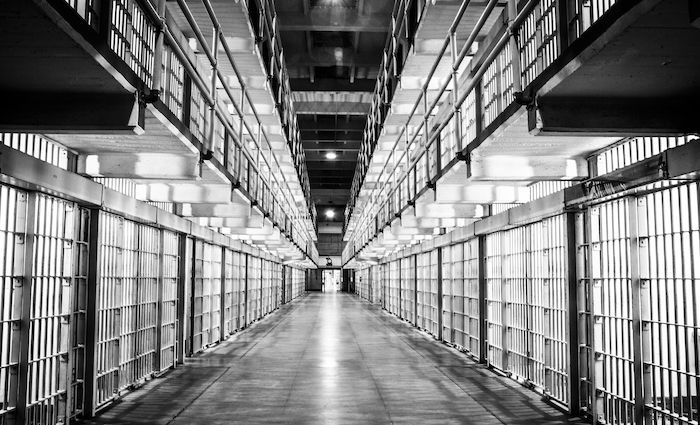

The warden’s mansion took up the top level, the barracks the middle, and the cells were below. A massive marching ground took up some of the space, but it ended up being primarily used as a playground and rollerskating rink for the children of the guards. There were four cell blocks: A, B, C, and D, but A was hardly used. In all, 336 cells were in use most of the time.

Approximately 110 men were needed to maintain order, but they rarely had more than 100 at one time. On average, 25 men were sick or on leave at any given time, which means they were constantly understaffed. (A scary prospect for a prison full of violent men.) In all, 1,576 prisoners lived on The Rock—far fewer than most people realized.

The Famous Prisoners of Alcatraz

Had some of the most notorious criminals not been sent to Alcatraz, it might have remained a bit of a mystery. Instead, one of the earliest trainloads of prisoners included Al Capone, the gregarious but sinister criminal who was only convicted of tax evasion.

As his heavily guarded and reinforced train crossed the great American countryside, people gathered to watch it pass. They dubbed it “The Al Capone Special.”

The prisoners at Alcatraz committed federal crimes or had attempted (sometimes successfully) escape from other prisons. Most of the time, the system transferred prisoners from other prisons rather than sent them here first. Severe behavioral problems in other prisons became a key qualification for transfer to Alcatraz.

Cory Kincade put together an impressive book about the profiles of the most prominent prisoners at Alcatraz. Here are a few from his list and the years they were housed there.

- Al Capone; #85; tax evasion; 1934–1938 (his last year was spent in the hospital due to syphilis)

- “Machine Gun” Kelly; #117; kidnapping; 1934–1951

- Roy Gardner; #110; robbery; 1934–1938

- John Paul Chase; #238; murder and robbery; 1934–1954

- Alvin “Ol’ Creepy” Karpis; #325; murder, robbery, kidnapping; 1936–1958

- Doc Barker; #268; murder, robbery, kidnapping; 1935–1939 (many of the Karpis-Barker gang were here at the same time)

- “Birdman” Robert Stroud; #594; murder; 1942–1959

- Mickey Cohen; #1518; tax evasion; 1961 (released on legal grounds); 1962–1963 (recaptured and sentenced again)

- Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson; #1117; racketeering and heroin dealing; 1954–1958

- James “Whitey” Bulgar; #1428; rape, murder, robbery; 1959–1963

Famous Movies About Alcatraz

Hollywood never fails to make a grandiose movie out of a seemingly unimportant person, and the prisoners and mystery of Alcatraz provided plenty of fodder. Burt Lancaster portrayed Robert Stroud in the movie Birdman of Alcatraz. Ironically, it’s a terribly incorrect movie as Stroud raised the canaries when he was incarcerated at Leavenworth, for starters.

Surprisingly, the movie aroused people’s deep sympathies for Stroud, and Alcatraz was soon inundated with letters appealing for his release! Apparently, people had fallen for Burt’s portrayal, not Robert himself. In truth, the real Birdman was “an eccentric, raw, avowed pederast [pedophile] who had murdered two men” according to author Jolene Babyak who grew up on the island when her father was an officer there.

Other famous movies include Escape from Alcatraz and The Rock, though they are also not entirely accurate either. Escape from Alcatraz is based on the impressive escape of Frank Lee Morris and brothers Clarence and John Anglin. However, the folklore behind these movies has served to keep the aura of brutality and secrecy about Alcatraz alive.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if San Francisco tours are worth it.

Prison Life

The first warden of Alcatraz, James A. Johnston, had been a progressive reformist in other prisons. Yet he had to change his methods for the purpose of Alcatraz inmates. He instituted a silent system where prisoners absolutely could not speak to each other. It was difficult to enforce and mentally brutal for the prisoners. The torturous treatment lasted for about four years before being revoked.

In terms of prisons, Alcatraz was no more brutal than most other prisons—in some ways, less so. The guards had minimal interactions with prisoners unless a prisoner acted out. That earned them time in the hole or solitary confinement where they only had a drain as a toilet and nothing else.

Unlike many other prisons, the food was actually quite good and prisoners could take as much as they want. However, they had to finish what they took, otherwise they would lose their next meal.

Visitors were allowed once a month and only for 90 minutes. They could not touch the prisoner, only sit with a glass wall between them and speak on the phone. Imagine how difficult that was for inmate families who traveled from the East Coast. A 90-minute visit after days of travel!

Babyak recalled that the biggest problem in the prison wasn’t brutality but extreme boredom for both guards and prisoners. However, brutality existed between the inmates themselves. An inmate’s life was at risk every moment in the yard or at work. Guards were completely unarmed and didn’t even have keys. A tower guard would lower the keys or another guard would let them in, according to Dunbar.

Routines And Changing Times

Morning began at 6:30 a.m., breakfast at 7:00 a.m., then work or yard time until lunch at noon. After lunch, they were taken to their cells for a period, then released again for work or yard time. Dinner was at 5:00 p.m. and lights out happened at 9:30 p.m. A count was taken at every single movement.

As another difference from other prisons, any time spent in the cells happened with closed doors. Prisoners only fraternized in the yard. They could work in the laundry or machine shop and earn $0.10 to $0.30 per hour. Prisoner Ben Rayborn managed to help his daughter with college expenses on this income.

In the later years, rules relaxed and prisoners were given radios in their rooms. Guards interacted more with prisoners. Room tosses happened less frequently and contraband became more common. It was exactly this lapse that lead to the infamous escape when prisoners obtained a magazine that happened to have detailed information about inflatable life rafts.

Family Life On Alcatraz

It may surprise many to learn that Alcatraz had at least 60 families with children on it at any one time. These families lived in fully furnished apartments and the children took the ferry to school and back. In the greatest of ironies, families felt more safe living on a prison island than in a busy city.

There was no crime or city noise, and they knew all their neighbors. Parents worried far more about their children falling off the cliffs while playing on the old cannons than about the prisoners.

Many former residents loved the 360-degree views in the bay on their island paradise. They even held Christmas parties where teens could invite their friends. Most children had little interaction with the prisoners though they often made up stories about them from a distance. Some men would wave to them or even throw balls back-and-forth with them through their windows.

When an escape attempt happened, a siren would blast through the air and all residents went on immediate lock down. They couldn’t leave until their apartment was searched by a guard and the “all clear” was given. Even then, they didn’t feel in danger because it was hard enough for a prisoner to get to shore, much less with a hostage.

The hardest part of island life was getting goods there. Residents recounted to Babyak the anguish and hilarity of dropping expensive items into the bay: an $800 color TV, mattresses, beer, food, etc. Additionally, the old power system was failing and electricity was often spotty. However, residents were disheartened to learn their homes would be closed in 1963 as they had developed deep bonds together on the tiny island.

Escape Attempts From Alcatraz

Jolene Babyak noted that in the 29 years of Alcatraz’s operation, only 14 escape attempts were made. Just 36 of the escapees made it down to the bay, and of those, 21 were recaptured, seven were shot, one drowned, two returned and were executed for killing a guard, and five remain missing.

The “escape-proof” prison wasn’t so perfect. The first attempt in 1936 was Joe Bowers who made a run for it before getting shot by guards at the fence. It’s suspected he intended to be shot as a suicide.

On December 16, 1937, Theodore Cole and Ralph Roe became the first to jump into the icy waters of the bay. It might seem that insanity was at play since the bay is frigid even in the summer. Prisoner “Blackie” Audett claimed he watched them flounder and drown.

The first escape that killed a guard happened in May of 1938. James C. Lucas, Thomas Limerick, and Rufus “Whitey” Franklin killed Officer Cline with a hammer and tried to escape. Limerick made it to the tower before being shot dead. The other two were captured and convicted with life imprisonment.

An ironic escape happened on April 14, 1943. Harold M. Brest, Floyd Hamilton (linked to Bonnie and Clyde), Fred Hunter, and James Boarman bound and gagged Officer Weinhold and made it down to the shore. Brest and Hunter were recaptured. Bourman was shot.

Hamilton was announced as drowned, but apparently, he swam until he got too cold, then returned and hid in a cave for three days. Totally hypothermic, he climbed back into the prison machine shop where Officer Weinhold found him sleeping near the radiator. He’s the only inmate to escape into Alcatraz.

The Battle of Alcatraz

The most violent escape happened on May 2, 1946. Bernard Coy and several others managed to get into the gun cage where the only guns were kept. Armed and dangerous, they proceeded to overpower guards at each cell house and release prisoners. They failed to shoot the tower guards who were now shooting back.

Fearing witnesses, they decided to shoot the officers they had trapped in the cells, killing two and wounding others. The rioters telephoned upstairs claiming they would take hostages, but they never made it up the stairs.

Warden Johnston had no idea how many prisoners were loose and had no training for an armed rebellion. Officers were sent in who began shooting at everyone, including friendlies. Eventually, they rescued the trapped guards, but by then Johnston had called for reinforcements from the military and local prisons to deal with the still-rioting prisoners.

The next day, Marines dropped grenades down the vent shafts and gassed the cell blocks until the shooting stopped. Two prisoners were tried and executed, but the youngest, Clarence Carnes, was given his third life sentence.

The Notorious Morris-Anglin Escape

Babyak noted that Guards were hard to come by after the Battle of Alcatraz, and rules relaxed under the fourth warden, Olin G. Blackwell. Many new officers were untrained and the old guard despised their fraternization with prisoners. The prison itself had literally been crumbling in both the foundations and the towers that were left unmanned due to expenses.

On June 12, 1962, three face-painted dummies with human hair were found in the beds of Frank Lee Morris and Clarence and John Anglin. By then it was too late. For nearly 10 months, they had dug holes around the vents that led to the back utility corridor.

Fellow inmate Allen West had helped plan the escape when he worked unsupervised back there and discovered how decrepit the system was. (He claims he couldn’t get his vent off to join them, but he also was afraid of water.) They were able to climb out, then shimmy up the pipes to the cell house roof space.

No one noticed them in the roof because they had put 30 to 50 blankets up for days, hiding their plans, while the guards assumed it was to keep the walls safe during painting. According to Babyak, no official report of the blankets exist, though every prisoner and many residents remembered them.

How They Did It

Thanks to a smuggled magazine with an inflatable life raft on it, the prisoners had decided to build one using 50 to 60 rubber-backed cotton raincoats. It measured 6×14 feet. They also made several life jackets. Ingeniously, the inmates sealed the life rafts and life jackets by pressing the seams against hot steam pipes. Many of the tools left behind in the roof included a vacuum motor, piping, scrap metal, a homemade flashlight, and wooden paddles.

The loud bang when they opened the ventilation door on the roof should have alerted the guards to do a stand-up count—as they would have under previous leadership. Instead, a simple search turned up nothing. Several key towers were unmanned that would have given direct line of sight to the escaping prisoners on the roof. Instead, the escapees vanished without a trace on the night of June 11.

A waterproof bag of names, addresses, photos, and receipts was found in the bay along with a paddle. A family in Marin City found a crude life preserver washed up on the 22nd, and a second was found east of Alcatraz in the water. Some decided the life jackets had slipped off the drowned bodies. No robberies occurred anywhere nearby for the men to collect supplies.

They completely vanished but were not necessarily presumed dead. Rumors of ugly women in heavy makeup at Anglin family funerals abounded. The search for these prisoners became the largest manhunt since the Lindbergh baby kidnapping. They remain missing, presumed dead, to this day.

The Fate of Alcatraz

The next escape attempt by the Scott-Parker team seemed to be the final nail in the coffin, though the end of Alcatraz had been looming for months. With the successful Morris-Anglin attempt, the prison had lost its escape-proof notoriety and had little credibility left.

Furthermore, Babyak discovered that according to then Bureau of Prison’s Director Bennett, it cost $13.81 per day prisoner at Alcatraz, compared to $5.27 per day at other prisons. It cost a fortune to ship every needed item. Guards made less than sanitation workers in the city.

The original military infrastructure experienced electrical blackouts all the time and $6 million of repairs were needed, according to author Donald Hurley. The Bureau of Prisons shut it down and the last prisoner left on March 21, 1963.

In November of 1969, the Indians of All Tribes organization led by Richard Oakes, an Akwesasne Mohawk, occupied the island. Under an old treaty, a group of around 100 Native Americans (mostly UCLA students and many Lakota) claimed ownership of the abandoned federal property. It served to remind them of their heritage as a proud people and sparked a revolution among Native Americans around the country.

Sadly, the island became overrun with other groups and many fires broke out. The tribes realized they couldn’t afford the upkeep either. Richard Oakes’ daughter tragically fell to her death, and the group abandoned their hopes for the island.

In June of 1971, U.S. Marshals moved everyone off the island before it was added to the Golden Gate National Recreation Area under the national park system in 1972. Many apartments were demolished for safety reasons, but tourists can take trips to see the island and explore many of the safer areas. It’s now returned to its heritage as a popular nesting site for many local birds.

To Learn More About Alcatraz

There’s so much fascinating information about this unique piece of history. We recommend checking out the books we used as references for this article.

Eyewitness on Alcatraz by Jolene Babyak

Alcatraz Most Wanted: Profiles of the Most Famous Prisoners on the Rock by Cory Kincade

Alcatraz Island Memories by Donald J. Hurley

Alcatraz by Richard Dunbar

But nothing beats seeing this mysterious island for yourself. Book a tour of Alcatraz on your next trip to San Francisco!

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if San Francisco tours are worth it.

Where To Stay in San Francisco

Make the most of your visit to San Francisco by choosing to stay in the best neighborhoods for seeing all this iconic city has to offer. You’ll love our hotel recommendations.