Fascinated by Italian painter Caravaggio’s artwork but unsure which paintings to see or where to find them? We can help you! Our guides have shared the secrets of the baroque artist’s work with many tour groups! Here are Caravaggio’s most famous paintings and where to find them.

The 11 Most Famous Oil Paintings By Caravaggio

Caravaggio’s paintings were transgressors in the eyes of his contemporaries, according to scholar Mieke Bal. The Italian artist worked extensively with the contrast between pleasure and suffering, illusion and reality, and religion and myth.

Often, he painted things that were seen as taboo. Caravaggio was indeed a rebellious provocateur. And his own life was a reflection of this. Born in 1571 in Milan, Caravaggio trained as an artist in Peterzano’s studio in 1584.

After that, he moved to Rome in the 1590s and started his career as both a painter and criminal. Author Felix Witting explains that Caravaggio committed a series of crimes. Some of these even included violence and defamation. Eventually, his criminal life lead him to the seemingly accidental killing of Tommasoni in a gang duel in 1606.

He quickly moved to Naples under the protection of the Colonna family. Between 1607 and 1608, he tried to get a pardon in Malta from the Knights of the Order. With no luck, he returned to Naples after a short stop in Sicily. In a final act of despair in 1610, he went to Rome to seek a pardon from the pope himself. He died in transit.

The cause of his death was unclear for a long time. However, a recent study of his remains by Michael Drancourt and his colleagues confirmed that he died from sepsis. It seems a wound he sustained in Naples after a fight got infected and eventually killed him.

Now you know a bit more about his story, it’ll give you a different perspective on his work. Here are Caravaggio’s most famous artworks and where you can see them for yourself.

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if Rome tours are worth it.

11. Basket of Fruit

c. 1599 | Oil on Canvas | Biblioteca Ambrosiana (Milan)

This painting is a classic piece of baroque art. Throughout this movement, artists tried to capture the realism of life. Still-life paintings were important pieces to show an artist’s mastery to achieve a likeness of everyday objects.

According to Felix Witting, this type of painting with natural elements was very prominent at the beginning of Caravaggio’s career, and perhaps his inception point of genius. However, Witting also states that Caravaggio discovers very early on that, despite how good he is at this type of painting, it’s not for him.

He didn’t feel any kind of emotion in this art form. So, he moved to work on human narratives. In fact, Caravaggio even rebels a bit in this otherwise perfect painting. If you look closely, you’ll see he’s incorporated elements of decay, such as worm holes and fallen leaves, none of which meet the picture-perfect ideals of this era.

Where to see it: Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our Milan Guide for more resources.

10. Judith Beheading Holofernes

c. 1598-1602 | Oil on Canvas | Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica (Rome)

This painting depicts the biblical passage from the Book of Judith where Judith gets the Assyrian general Holofernes drunk and then cuts his head off. Caravaggio decided to paint the most impactful moment: when Judith is severing the head.

Look closely at the expressions in the scene and you get a much deeper feeling for the psychology of this painting. Aside from the obvious surprise and agony of Holofernes, Judith’s expression is full of disgust, struggle, and uncertainty. Her helper looks on intensely too, albeit away from the scene. Perhaps she is keeping an eye out in case someone discovers the gruesome scene.

According to Andrea Pomella, this is the first painting in a series of works where Caravaggio explores the tragic meaning of life. The striking realism and expression on the faces convey the anxiety of the painter.

Author John L. Varriano explains this is also the first painting where Caravaggio starts using incisions in the materials to carve contours, which reinforces the contrast between light and dark in his tenebrism style.

Where to see it: Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome

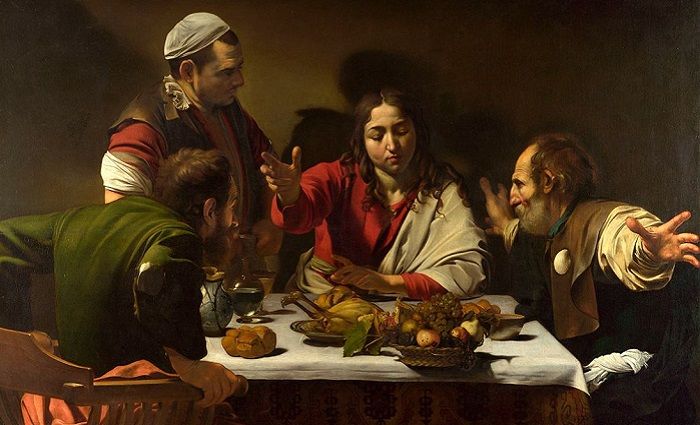

9. Supper at Emmaus

1601 | Oil on Canvas | National Gallery (London)

The Gospel of St. Luke inspired this scene, which depicts the moment when, after his resurrection, Jesus appears to his disciples in the town of Emmaus.

According to Larry Keith, this is one of Caravaggio’s most highly touched-up paintings and required a great amount of planning and preparation. Overall, we can see a more sophisticated development of his artistic skills.

If we compare this painting to the same version of the Supper at Emmaus in Milan, we notice that the London version uses light and contour more softly. There’s more colour, which helps create dynamism in the scene.

The more elaborate composition creates drama, instead of the stark tenebrism of the Milan version. According to Giulio Bora, this is because, in the London version, he borrows from the mannerism techniques we can see in Michelangelo or Raphael.

Where to see it: National Gallery, London

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if London tours are worth it.

8. The Taking of Christ

1602 | Oil on Canvas | National Gallery of Ireland (Dublin)

According to Andrea Pomella, the dramatism of this scene shines through the entangling of the bodies in the painting. Even though there is no clear setting or background to this scene, the figures alone and the drama created are sufficient. This is the key moment when Judas betrays Christ in the garden.

The figures, from left to right, are John, Jesus, Judas (who has just kissed Christ), and three Roman soldiers. Finally, there’s a man holding a lantern, which is the point of light that Caravaggio uses for his tenebrism technique in this scene.

This painting was believed to be lost for about 200 years. At the end of the 17th century, it was accidentally attributed to one of Caravaggio’s Dutch followers. This happened during the inventorying of a large art collection that hosted this painting, so its origin was confused.

Thankfully for us, the senior conservator of the National Gallery of Ireland, Sergio Benedetti, found it amongst the collection of some Jesuit priests in Dublin in the 90s and expertly identified it as an authentic Caravaggio.

Where to see it: National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

Not ready to book a tour? Read more in our Dublin Guide.

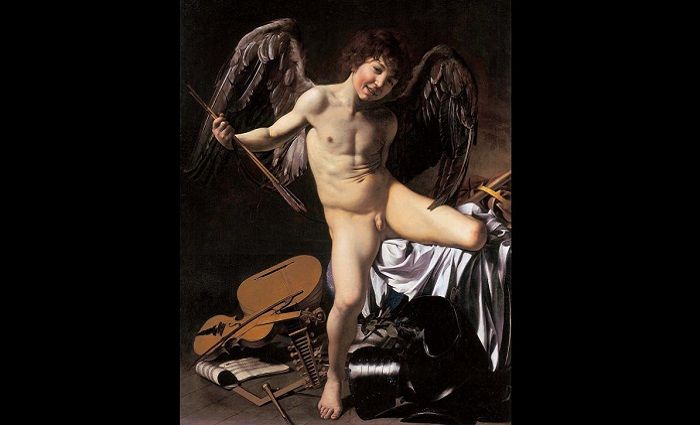

7. Amor Vincit Omnia

1601-2 | Oil on Canvas | Gemäldegalerie (Berlin)

The theme of the painting is clear: love conquers all. Here we see Cupid trampling over items related to reason, science, and war. This is, in fact, a fairly common subject of the time, but Caravaggio’s twist turned it into an instant classic.

We know that Caravaggio worked with a model for this painting. The realism showcased here is almost photographic. In fact, there is a clear element of sculptural work in the creation of this piece and its structure, according to Bradford Kelleher. Also, David Stone notes that this is a clear example of Caravaggio’s irreverence towards classicism.

If we look at this Cupid, he is charming but far from the beautiful god of ancient history. He has crooked teeth and appears incredibly childish, which is very far removed from the angelic and platonic Cupid of the Renaissance and Ancient Rome.

Where to see it: Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

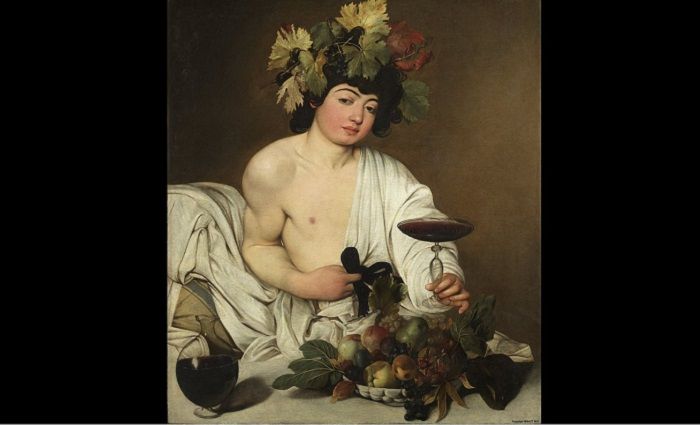

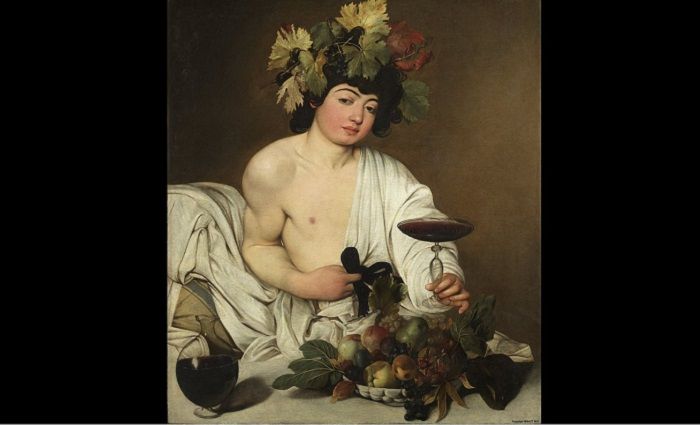

6. Bacchus

c.1596 | Oil on Canvas | Uffizi (Florence)

Although depictions of the classical gods were popular during the 1500s and 1600s, this painting of Bacchus is not conventional. According to Witting, Caravaggio painted the god as an androgynous figure. Bacchus’ gesture and posture actively engage with the viewer by offering them a cup and inviting them to rejoice in terrestrial pleasures.

In this painting, state Kelleher and Gregory, we can see better than anywhere else in Caravaggio’s portfolio the impact of the Cinquecento influences from artists in Brescia, Italy. They explain that the tri-dimensionality and illusion effects we see here are direct borrowings from painters such as Moretto and Salvodo.

Art historian Ann Sutherland Harris says this is the most polished of all the half-length paintings of young men that Caravaggio produced early in his career. She also points out that this is one of the few paintings that was never copied.

Harris proposes that the deviation from the traditional depiction of Bacchus may perhaps suggest that Caravaggio didn’t intend to paint the god himself, but rather someone dressed up as him.

Where to see it: Uffizi Gallery, Florence

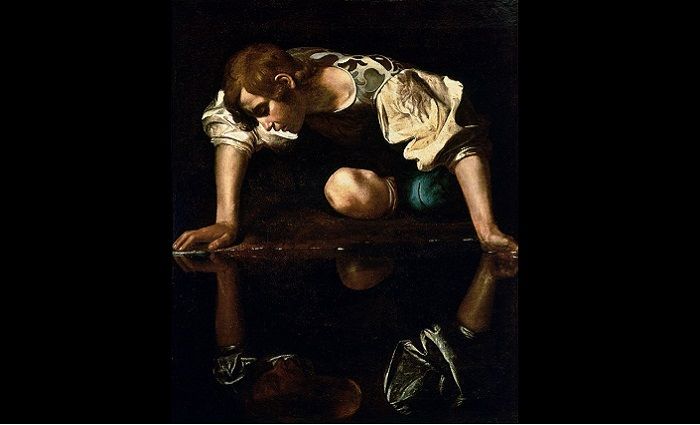

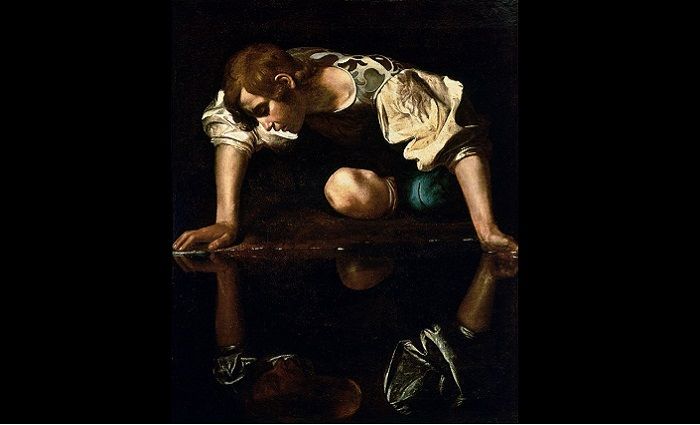

5. Narcissus

1597-99 | Oil on Canvas | Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica (Rome)

This is another painting by Caravaggio, according to Mary Ann Mattoon, that transforms art and the way we see the story of Narcissus. The trick is all in the water. Caravaggio uses his mastery of light and shadow, along with his realism of movement and form, to create two parallel images of narcissus.

One stands in the light, which is the Narcissus that contemplates his reflection. The other is in the darkness of the water that will bring his doom.

In other paintings, Mattoon says water was traditionally used as a direct mirror or a calming effect. Here, however, Caravaggio achieves troublesome anguish that drives the narrative. Due to the composition of this painting, we also get a general sense of fragility and a lack of stability.

You might also see that the centre of gravity is off balance. So, if you view this painting in person and feel a little dizzy, lightheaded, or slightly off, don’t worry. This is normal. Just take a moment to sit down—you’ve fallen victim to Caravaggio’s mastery of perception and drama.

According to John Varriano, these mythological topics, particularly those where there’s one single figure, give us a glimpse into Caravaggio’s mind. He argues that although the motives may be borrowed from myth, pieces such as Narcissus also have a sense of self-expression. Arguably, one could read that this is a moment of acknowledgment from Caravaggio to himself, realising his own troubled life and the darkness that surrounded him.

Where to see it: Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome

4. The Cardsharps

c.1594 | Oil on Canvas | Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth)

If there’s a painting that represents the actual life that Caravaggio lived beyond his paintings, it’s this one. The picaresque that exudes throughout his life story comes across here, as he paints these people playing cards. It’s two people playing tricks on the other naïve person in the painting.

According to Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, Caravaggio knew the literary fashions of the time. And as often happens, one art method borrows from another. Aware of the successful picaresque novels from Spain with ruffians, tricksters, and ordinary people as their protagonists, he would have thought these characters perfect for his paintings. According to Ann Sutherland Harris, if we look closely, we notice that the characters in this painting are similar to those in The Calling of St. Matthew.

Also, we know that Caravaggio liked gambling. In fact, it’s likely that many of his fights happened because of games, debts, and egos hurt in the process. Pieces like this one acted as social windows and commentaries on the world around people like Caravaggio and his contemporaries. They are accounts of people who don’t often get an abundant historical record and they help us understand periods of history in a more holistic way.

Where to see it: Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth

3. The Calling of St. Matthew

1599-1600 | Oil on Canvas | San Luigi dei Francesi (Rome)

This painting is interesting because, according to Juliet Benner, it is full of spiritual power. The huge size of this painting in its current location (which is a relatively small chapel) means the message is impossible to miss. The pointing hand of Jesus to the tax collector Levi, who will later become Matthew, is a clear and commanding invitation to join Christ.

Marjorie Cohee Manifold explains that, if you notice the window on the upper area of the painting and follow the light to the pointing hand, this helps understand the story. Benner notes that the darkness of the room symbolizes Levi/Matthew’s soul, while the piercing light is the clear road to salvation.

This painting, Pomella states, was Caravaggio’s first prominent commission in the city of Rome. And it caused quite a commotion in Rome at the time explains Witting. This is easy to see when we consider that this painting was originally an altarpiece.

If you take a closer look, the five characters were actually gambling. Then, as Jesus comes to announce his mission, the scene breaks up. This would have looked rather out of place in a church despite the topic of conversion.

Where to see it: San Luigi dei Francesi Church, Rome

2. Medusa

1597 | Oil on Canvas Mounted on Wood | Uffizi (Florence)

Here, Caravaggio painted the very moment when Perseus cut off Medusa’s head. Unless you see this Medusa in the flesh, her gaze gets lost in translation says Mieke Bal. In this digital version, Medusa seems to be looking away, terrified by her fate.

However, on the convex surface of the shield that it was originally painted on, it becomes harder for us to know exactly where she’s looking or why. Bal explains that Caravaggio experimented with the concept of spatiality, often confusing and baffling his audience.

Unfortunately, this is one of the many issues we have with decontextualized art. Either way, the expression of absolute shock is as realistic as it gets, as is the perfect depiction of the snakes in Medusa’s head.

By now you’ve also seen a recurring theme of beheading in Caravaggio’s paintings. As historian Thomas Puttfarken explains, this is a reflection of his internal struggle and violence, which he develops through these scenes. They show torture and martyrdom in a very baroque and Christian dual nature, much like his life.

Finally, this piece is also important because of Caravaggio’s patron. It was the second artwork that Cardinal Francesco Del Monte commissioned from him. In fact, it is thanks to the patronage of this cardinal, diplomat, and art collector, that Caravaggio found his place as a stable artist despite his run-ins with the law. Without the help of people such as Del Monte, Caravaggio may have struggled to keep up his momentum.

Where to see it: Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if an Uffizi Gallery tour is worth it.

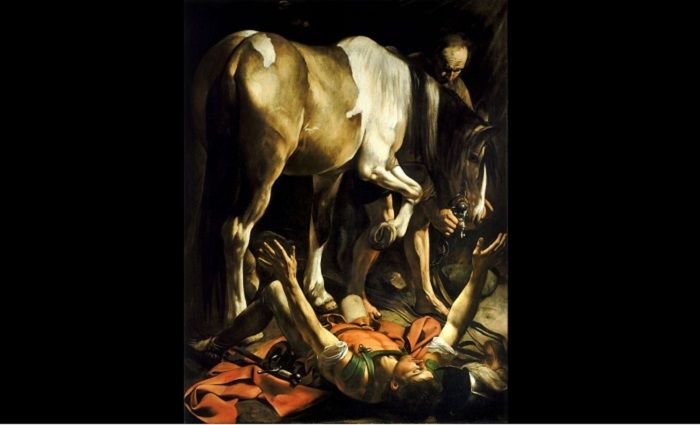

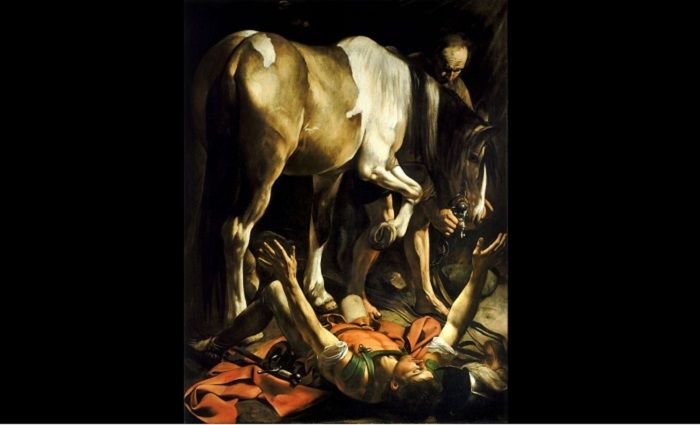

1. Conversion On the Way to Damascus

1601 | Oil on Canvas | Santa Maria del Popolo (Rome)

This painting perfectly shows Caravaggio’s famous chiaroscuro and tenebrism techniques. This is highlighted once again by the diagonal line creating perspective and directing the light. You can see this from the rump of the horse to its muzzle.

Also, authors George Van Kooten and Antonio Cimino point out that the way Caravaggio uses the light to shape St. Paul gives the impression that the conversion has already happened.

Saul is now Paul because of the grace of the Lord. Light surrounds his whole body. This suggests the mystical powers have now done their job. So, Paul is now ready to become a follower of Jesus.

To fully understand this painting, we need a little bit of biblical knowledge. The motive of St. Paul and his conversion is very powerful because it’s the ultimate tale of redemption. Saul (Paul’s name before converting) was a Pharisee who actively discriminated against Christians. His conversion demonstrated that even the enemies of God can find their way to the path to heaven.

Finally, the fact that Caravaggio had the opportunity to create paintings for the pope’s treasurer, Tiberio Cerasi, is remarkable on its own. It suggests that despite his troublesome background, his talent—at least at that moment—still outshined his criminal activities. According to the Menzies, he was like a “rock star.” Even the most powerful men in Rome could look the other way, momentarily, to get a masterpiece.

Where to see it: Santa Maria del Popolo Church, Rome

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our best Rome tours to take and why.

Surprised the execution of John the Baptist in Valletta Malta wasn’t in the list I went there just to see this one painting sends shivers down your spine